“Dnipro” in West Germany. The kgb’s Special Operation

2/8/2026

In 1956, the kgb of the ussr created a fake agent group “Dnipro” in West Germany, which supposedly held patriotic positions, cared about Ukrainian interests, and called on emigrants to return to their homeland. But behind these seemingly sincere appeals and calls there laid thoroughly thought-out and far-reaching plans to sow discord and enmity among Ukrainian emigrants, compromise their leaders in the eyes of ordinary members of nationalist organizations, turn them against each other, and sow despair. Declassified documents from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine reveal what was really hidden in the murky waters of the “Dnipro” and what techniques the kgb used to achieve this.

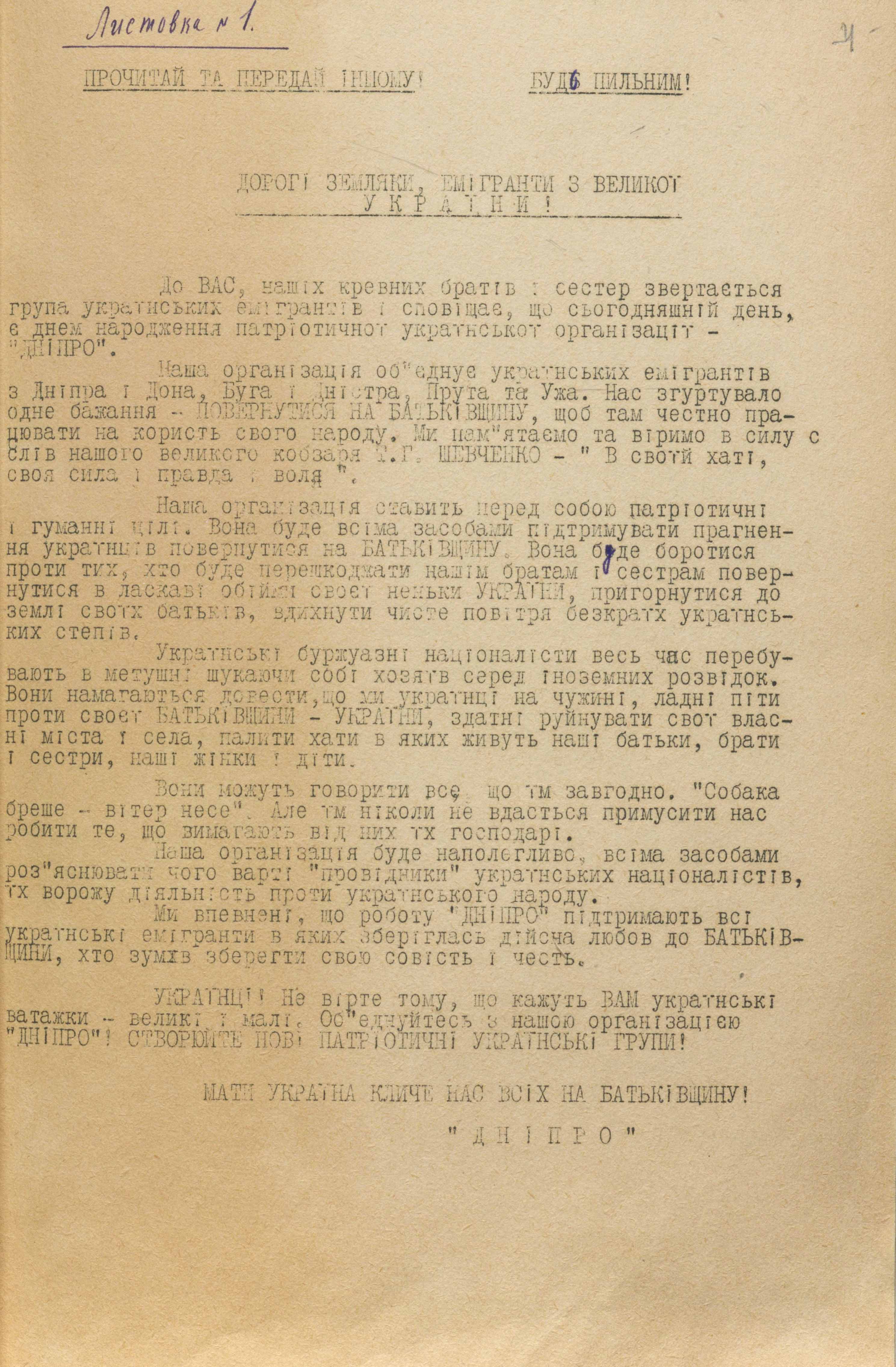

“Read and Pass It on!”

“Dear compatriots, emigrants from Greater Ukraine!

A group of Ukrainian emigrants is addressing you, our blood brothers and sisters, to announce that today is the day of birth of the patriotic Ukrainian organization “Dnipro”.

Our organization unites Ukrainian emigrants from the Dnipro and the Don, the Bug and the Dniester, the Prut and the Uzh. We are united by one desire – to return to our Motherland to work honestly for the benefit of our people. We remember and believe in the power of the words of our great kobzar, T. H. Shevchenko: “In one’s own house,– one’s own truth, one’s own might and freedom”.

Our organization sets itself patriotic and humane goals. It will use all means to support Ukrainians’ aspirations to return to their Motherland. It will struggle against those who prevent our brothers and sisters from returning to the loving embrace of their mother Ukraine, to embrace the land of their fathers, to breathe the clean air of the boundless Ukrainian steppes...”

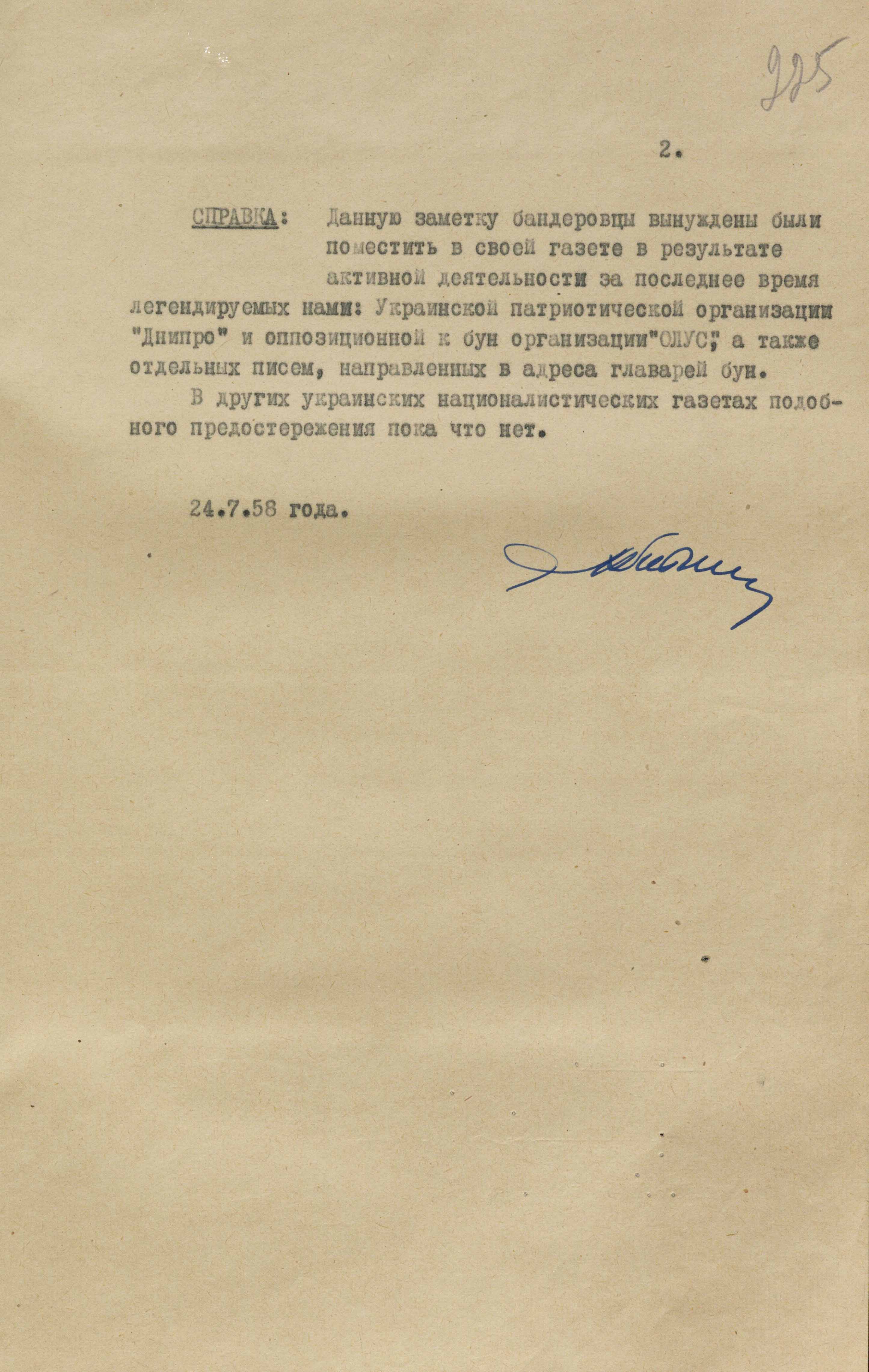

(FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10901. – Vol. 1. – P. 4).

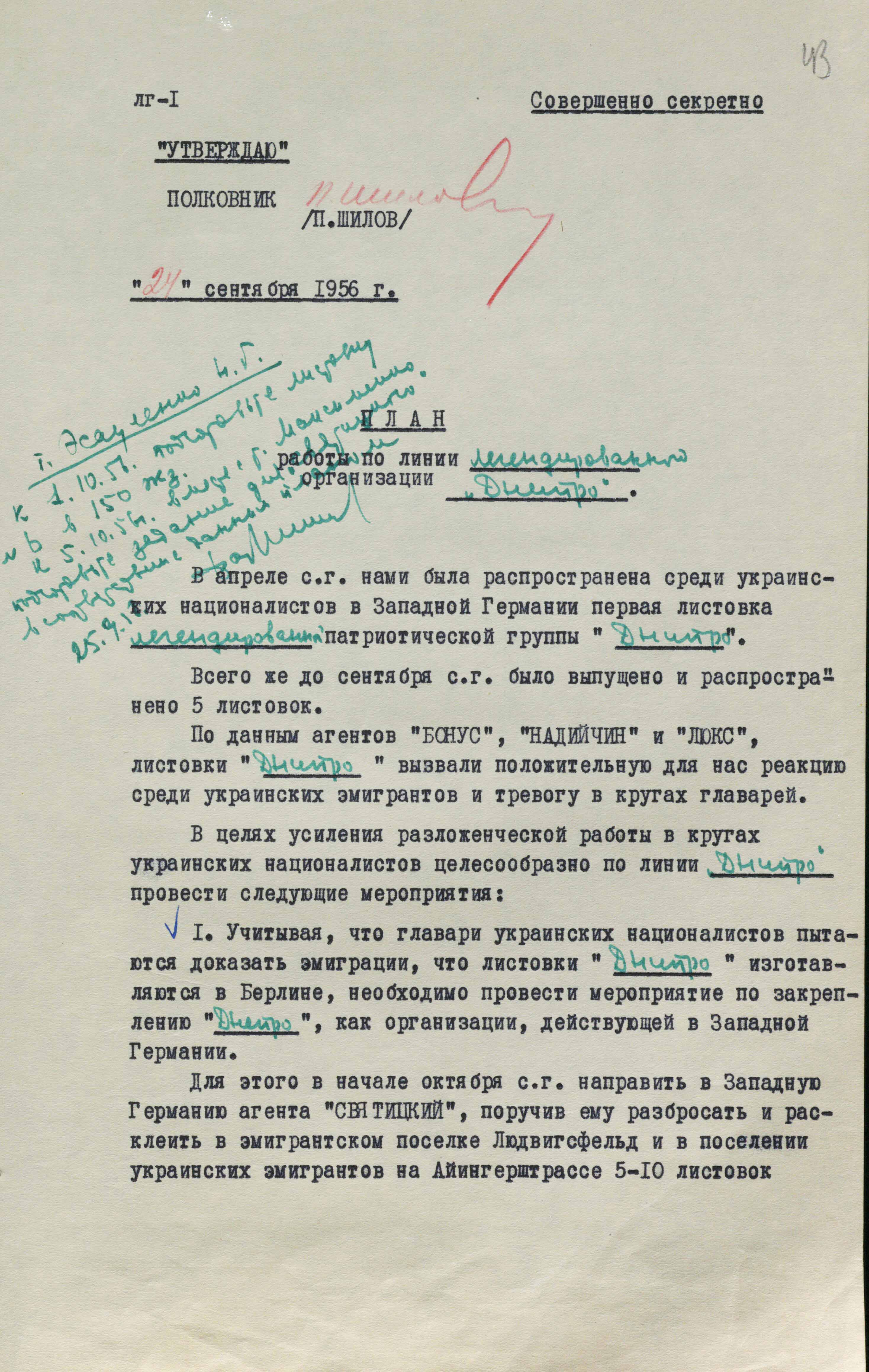

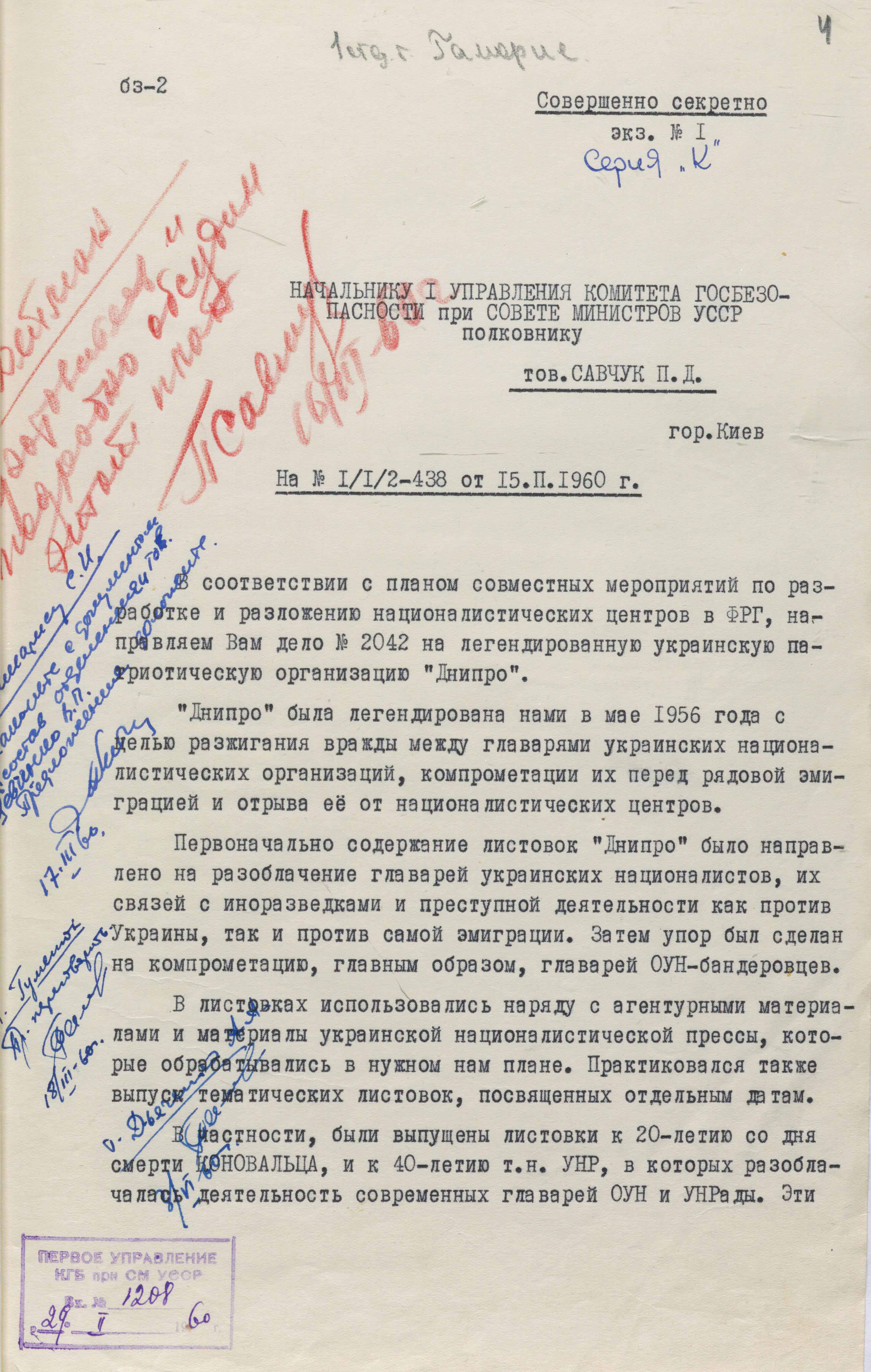

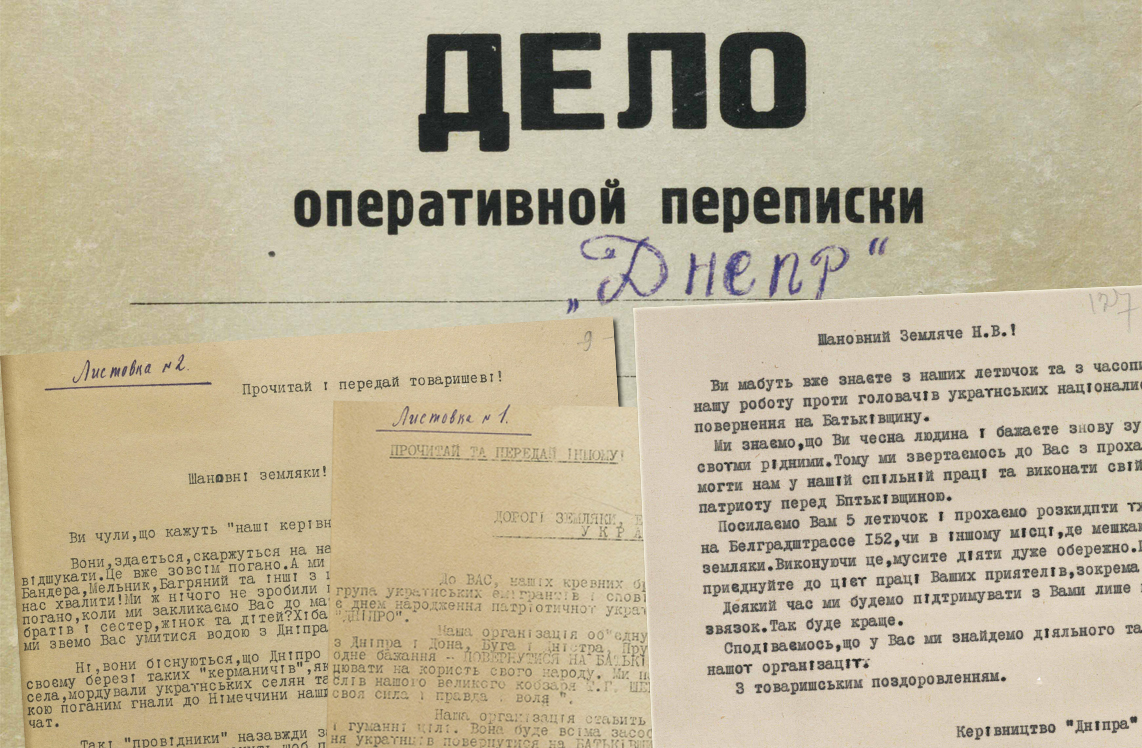

These words began the first leaflet which Ukrainian emigrants living in Munich and Hanover received in their mailboxes in April 1956. A total of 116 envelopes were sent out. Already signed, with specific addresses and surnames, they were handed over to two agents of the apparatus of the senior advisor to the kgb of the ussr in the German Democratic Republic. Their task was to travel to West Germany and send the letters to the addressees from there.

The senior advisor’s office was a fairly extensive kgb structure operating within the GDR’s state security agencies. Its employees coordinated the work of the East German special services in the interests of the ussr, and most importantly, independently conducted intelligence and counterintelligence activities from the positions of the GDR (and often “under the flag” of that country) throughout Europe. In particular, they planned all kinds of agent-operational measures, special operations, and so-called active measures against Ukrainian emigration centers abroad and their leaders. All the high-profile murders of Ukrainian figures, poisonings, assassination attempts, attempts at recruitment or compromise – all of those were carried out by that apparatus. It was there that operations were developed to assassinate Lev Rebet and Stepan Bandera, liquidate Mykola Kapustianskyi, drive Yaroslav Stetsko to his death, compromise Ivan Bahryany, and many others.

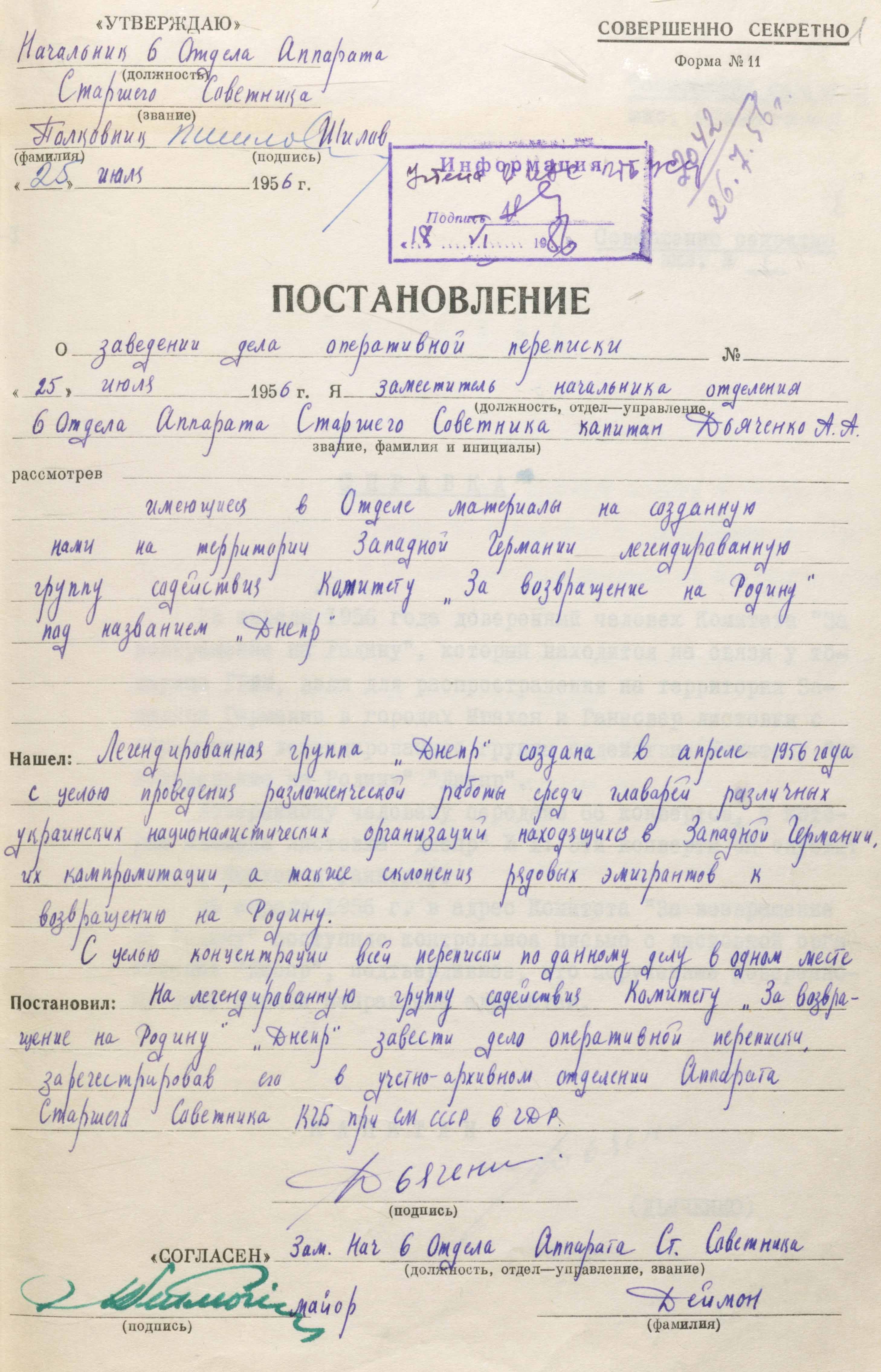

The idea of creating a fictitious group of Ukrainian emigrants called “Dnipro” was born in the 6th department of the apparatus. In the resolution to open the case, it appears as a legendary group assisting the committee “For the Return to the Motherland”. It was a soviet propaganda structure created in the early 1950s to work with emigrants, first of all political ones. The committee formally positioned itself as a public organization, but in fact it was an instrument of special services and operated under the full control of the mgb/kgb. Its main activity was to persuade former forced laborers, prisoners of war, and political refugees, including members of anti-soviet organizations, to return to the ussr, as well as to work against those organizations.

The committee’s main publication was the newspaper “Za Povernennia na Batkivshchynu” (“For the Return to the Motherland”). It was published in moscow and had several language versions, Ukrainian included. Its pages featured “letters of repentance from emigrants”, stories about “successful” lives after returning, statements about amnesty, and articles exposing members of emigrant organizations as bourgeois nationalists. There was also a russian-language propaganda magazine for emigrants called “rodina” (russian for “motherland” – Transl.) and an information and propaganda bulletin of the same orientation called “novosti rodiny” (russian for “News of the motherland”)

A characteristic feature of all publications was the mgb/kgb’s complete control over them and a unified style. This was manifested in the fact that they persistently emphasized the alleged mistakes of youth, their “sincere” repentance, and portrayed anti-soviet figures in a negative light. At this, they actively used elements of psychological pressure on forced emigrants: they played on concepts such as “fear of isolation abroad” and “shame before relatives and loved ones who remained in the ussr”; emphasized that they were unwanted in a foreign country, and made “promises of forgiveness for all past deeds and sins”.

In contrast, the creation of the fake “Dnipro” agent group and the production of leaflets and other publications on its behalf had all the hallmarks of a special operation. According to declassified documents, there was no list of group members, nor was there a real or even fictional leader. Only the name existed. The texts of the leaflets and other publications were written by staff members of the kgb apparatus located in Karlshorst, near Berlin. However, they were sent to recipients from West Germany in order to create the impression that the group was operating there. To this end, paper and envelopes manufactured in West Germany were purchased. The recommendations emphasized that the style of the letters, words, and phrases should not differ from how Ukrainian emigrants corresponded with each other, and that the envelopes should be addressed correctly.

The case includes lists of Ukrainians who lived in different cities and their addresses. So, some of the leaflets were sent to specific recipients by mail. To do this, agents were given stacks of envelopes and instructed to travel to West Germany and send the leaflets from there. Some of the leaflets were posted up by agents at bus stops and in building entrances. For wider distribution, the leaflets were marked with the words: “Read and Pass It on”.

“From House to House”

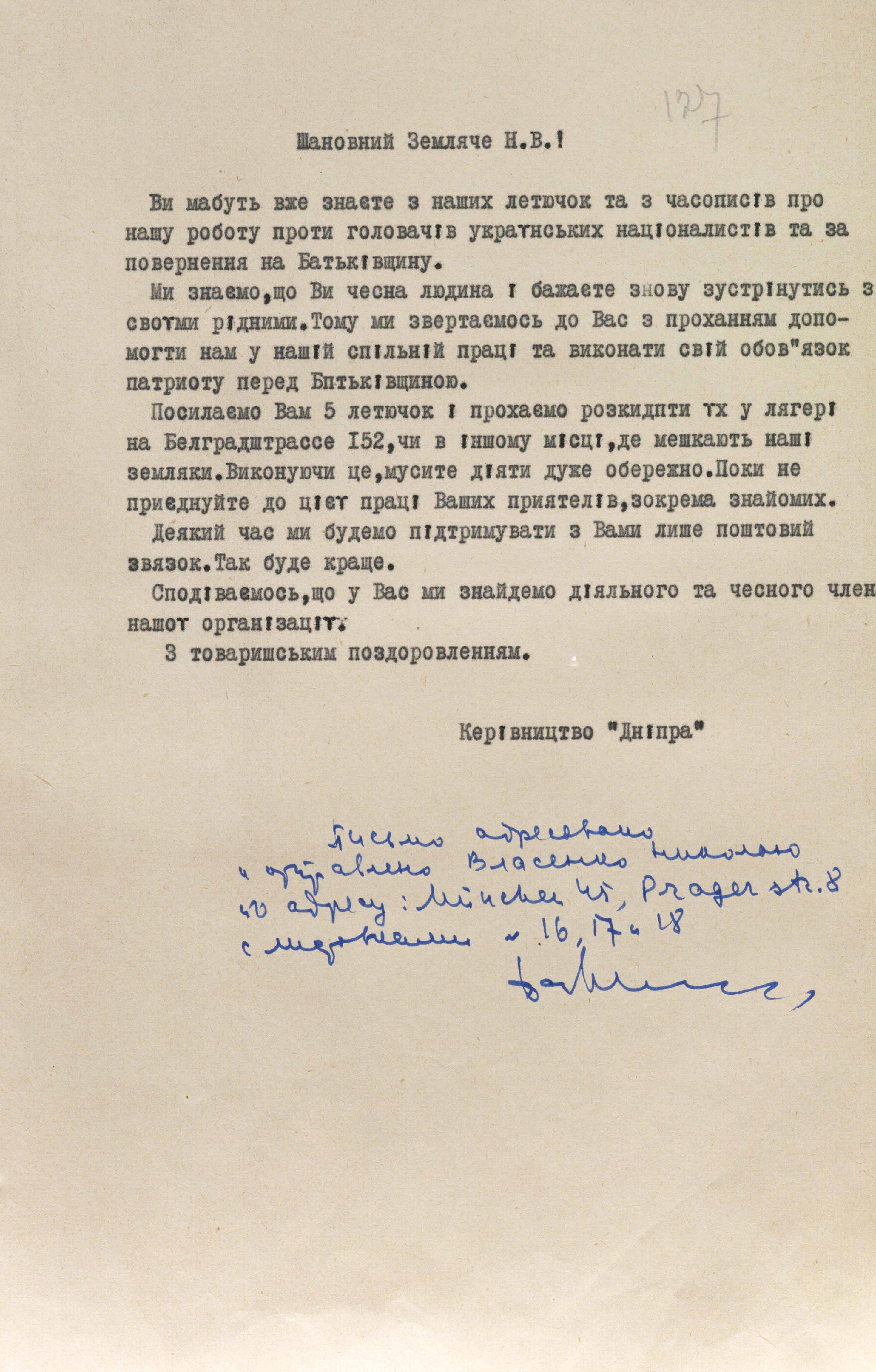

To make the leaflets appear as authentic as possible, the kgb used a specific style, Ukrainian dialects, and slogans from the period of the Ukrainian people’s struggle for independence. One such slogan was “From house to house”. But it was not only used in texts, it was also used as a method of influencing the target audience. In particular, after preliminary study, a number of emigrants were sent letters with the following content:

“Dear compatriot!

You probably already know from our leaflets and magazines about our work against the leaders of Ukrainian nationalists and for the return to the Motherland.

We know that you are an honest person and want to see your family again. Therefore, we ask you to help us in our joint work and fulfill your duty as a patriot to your Motherland.

We are sending you five leaflets and ask you to distribute them in the camp at Belgradstrasse 152 or in some other place where our compatriots live. In doing so, you must act very carefully... For some time, we will only maintain postal contact with you. It will be better that way.

We hope that we will find in you an active and honest member of our organization...”

(FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10901. – Vol. 1. – P. 127).

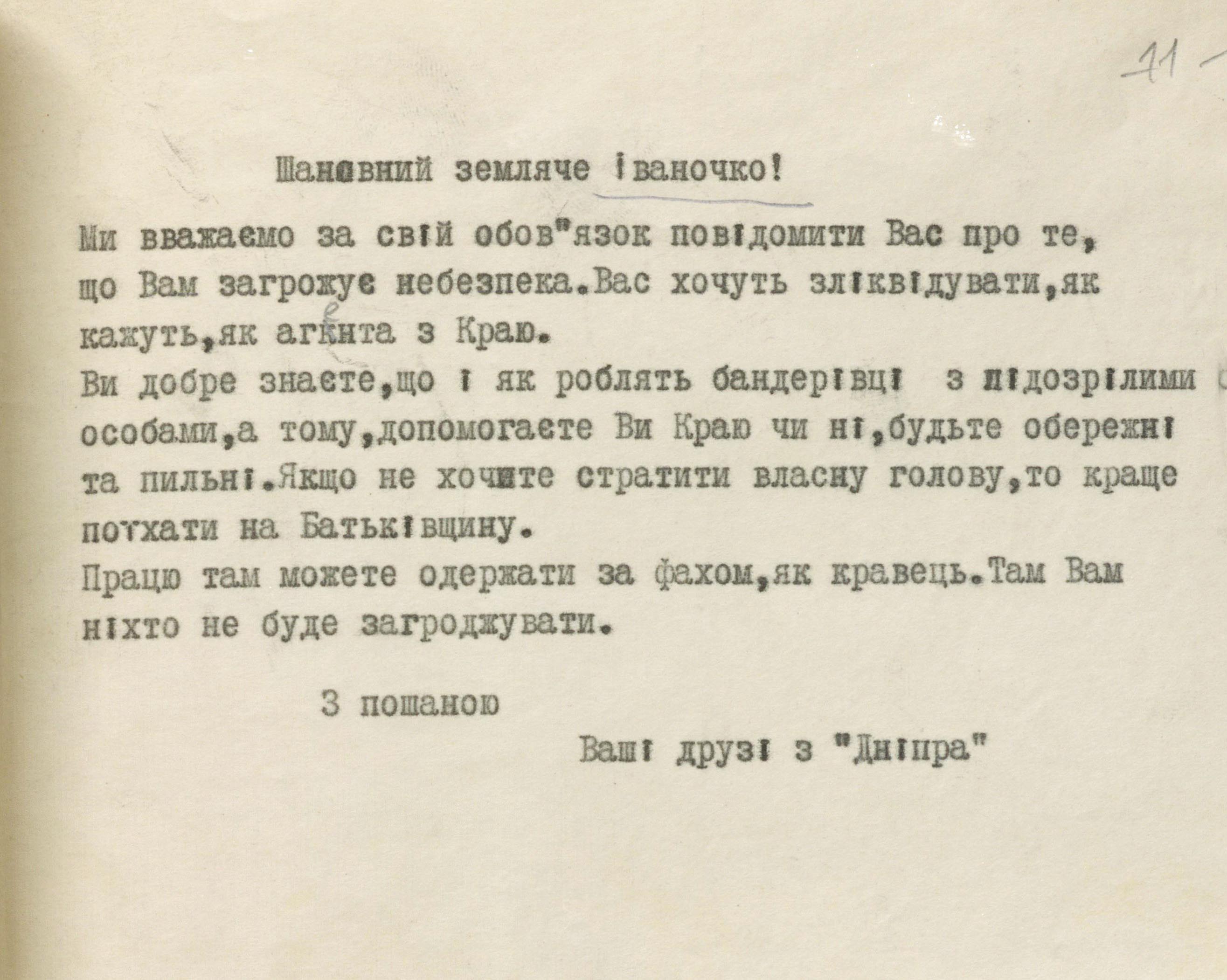

In this way, they tried to recruit supporters who could later be involved in other tasks. The case describes correspondence with one of the emigrants, Petro Ivanochko. The kgb learned that he was acquainted with some leaders of Ukrainian nationalist centers, in particular Ivan Kashuba, Yurii Studynskyi, and Danylo Chaikovskyi. They often visited his tailor’s workshop in Munich, where they not only ordered clothes but also talked about various topics. So, first they wrote him a letter with an offer to cooperate with the “Dnipro” group. As a sign of agreement, they recommended that he hang a piece of green fabric in the workshop window on Mondays and Fridays.

When the kgb did not receive the “green light” and learned that P. Ivanochko had told his visitors about the letter and reported it to the police, he received another letter from “Dnipro”. “We consider it our duty to inform you,” the letter said, “that you are in danger. They want to liquidate you, as a so called agent from Ukraine. You know very well what Bandera’s followers do to suspicious individuals, so whether you help Ukraine or not, be careful and vigilant. If you don’t want to lose your head, it’s better to go to your Motherland. You can find work there as a tailor. No one will threaten you there” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10901. – Vol. 1. – P. 11).

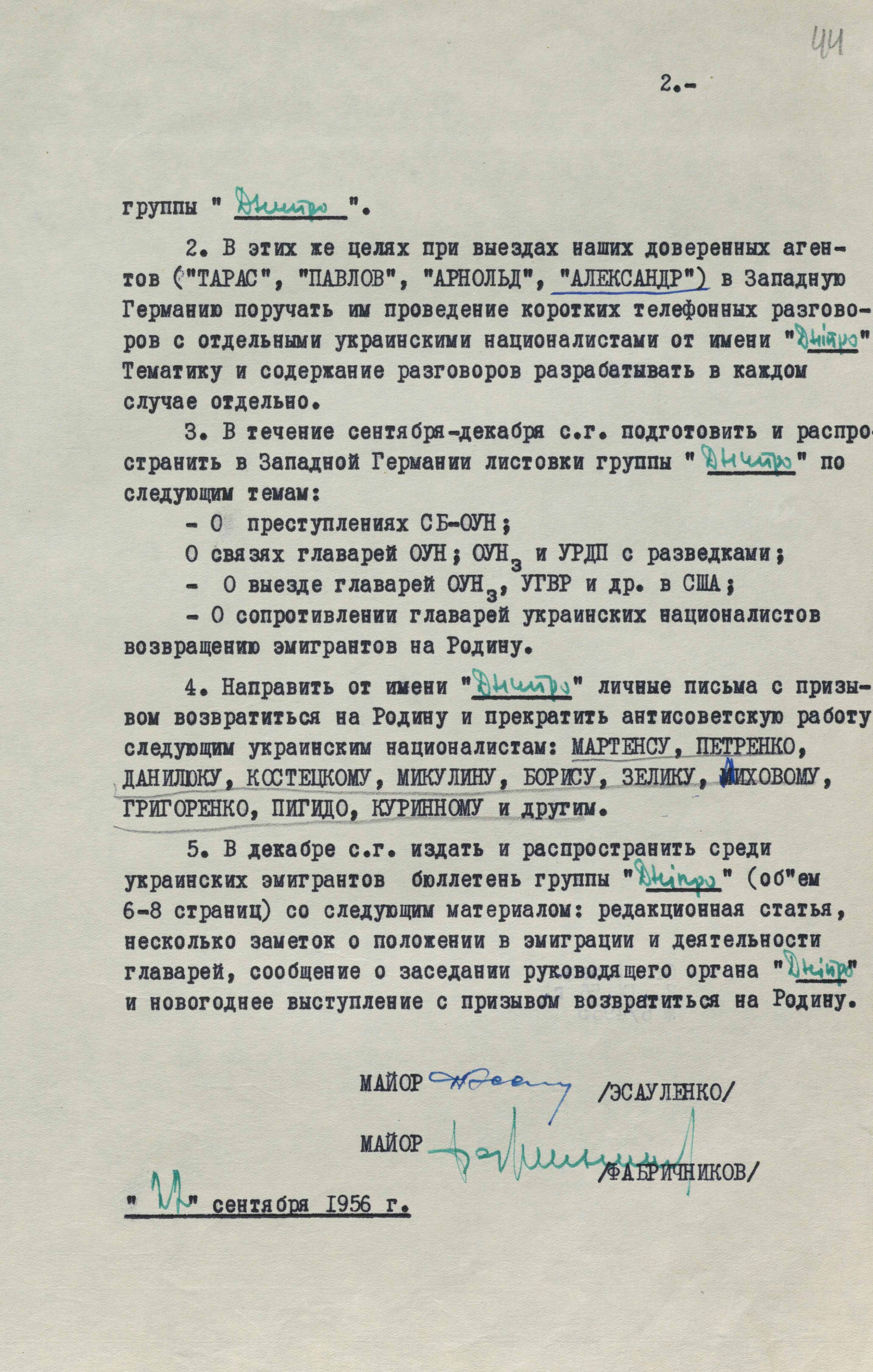

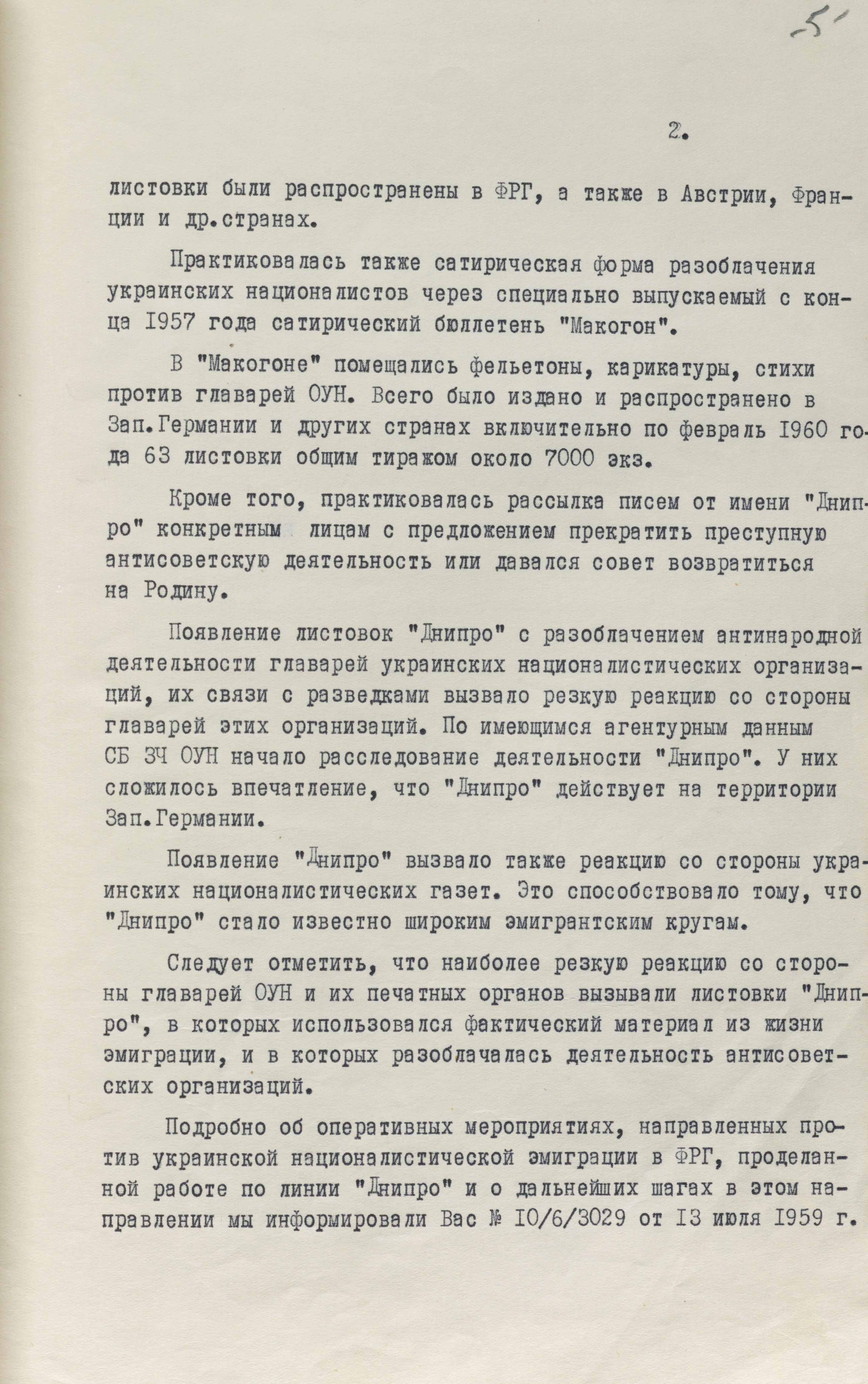

Similar letters were sent to other emigrants. However, the main emphasis was still placed on leaflets. During the first eight months, 13 leaflets with a total circulation of 1,000 copies were manufactured and distributed in West Germany. They described the allegedly difficult life of Ukrainian emigrants abroad, unemployment, and the lack of prospects for further stay there, and portrayed the role of the leaders of the OUN, UPRP, UNRada, and other organizations in a negative light. All this was presented in such a way as to turn some against others, arouse mutual suspicion, cause discord, and sow enmity.

Some leaflets were dedicated to S. Petliura, S. Bandera, A. Melnyk, Ya. Stetsko, S. Mudryk, L. Rebet, and I. Bahryanyi. Of course, they were all branded as traitors to the Ukrainian people, bourgeois nationalists, servants of imperialism, and agents of foreign intelligence services. At the same time, some of the leaders were portrayed as “bolshevik agents” in order to discredit them in the eyes of those around them. This was done as part of other so-called active measures by the kgb. Soon, a satirical newsletter “Makohin” was added to the leaflets. It featured caricatures of Ukrainian leaders in order to undermine their authority among ordinary members.

How did Ukrainians react to all that?

The Murky Waters of the “Dnipro”

According to declassified documents, after the first leaflet appeared, members of the OUN’s foreign units gathered for a special meeting to discuss the situation. Ivan Kashuba, who was in charge of OUN intelligence, immediately stated that this was not the work of Ukrainian emigrants. At the same time, he pointed out that the leaflets still had a certain influence on some ordinary members of the Organization, so it was necessary to actively work to expose those behind them. He was supported by one of the leaders of the OUN Security Service, Stepan Mudryk. They soon came to the conclusion that the leaflets were being produced in the GDR and from there were finding their way into West Germany.

After the kgb learned from its agents about the investigation by I. Kashuba and S. Mudryk, they immediately prepared new leaflets compromising them. At the same time, they became the subject of caricatures in “Makohin” as agents of the German and American secret services. But this did not prevent them from continuing to expose the “Dnipro” group.

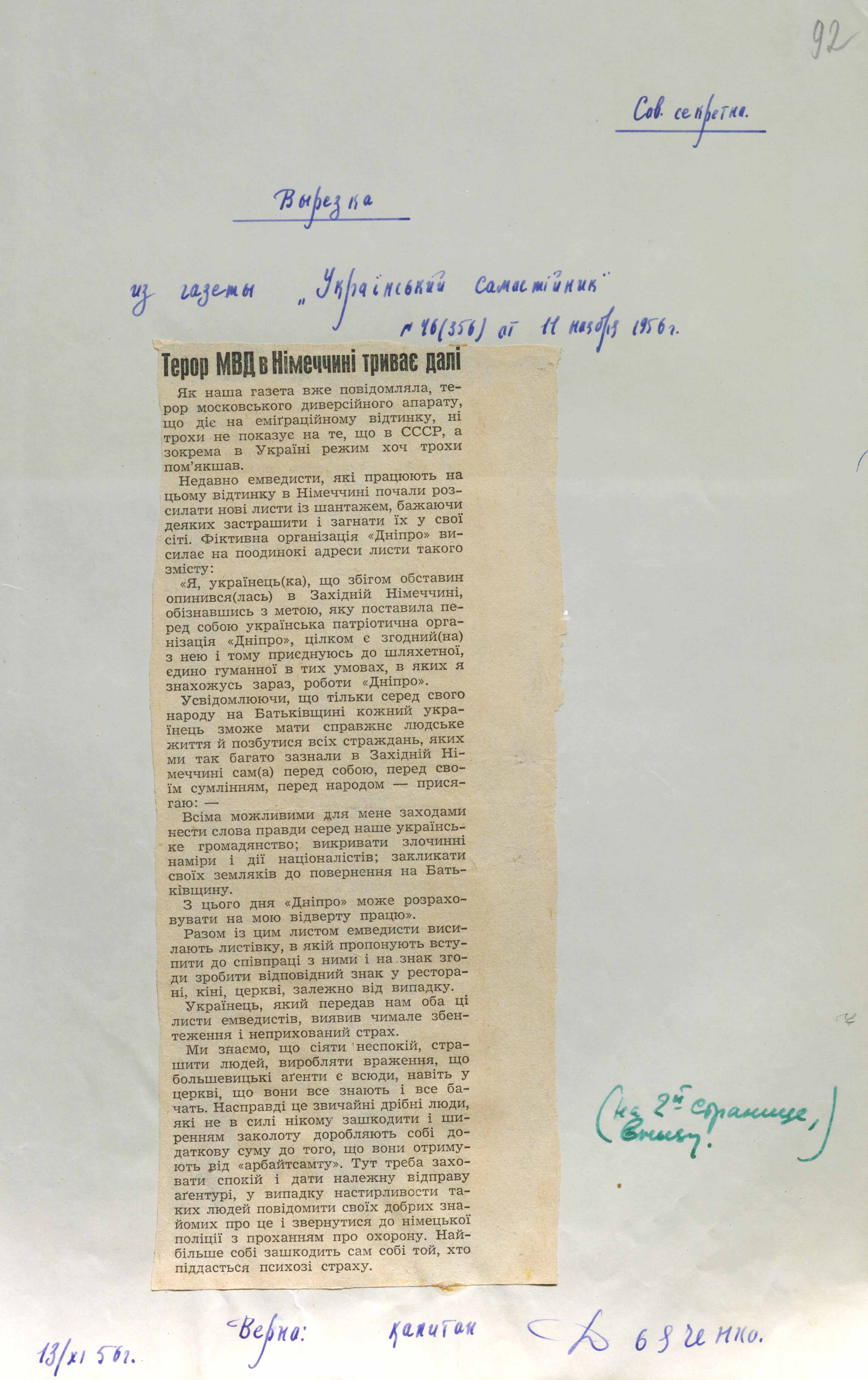

In September 1956, Lev Rebet’s article entitled “Victims of Their Own Blindness” appeared in the newspaper “Ukrainskyi Samostiynyk”. In it, the publicist and one of the leading ideologists of the OUN drew attention to the fact that Ukrainian emigrants were increasingly feeling the cold hand of moscow. “The touch of this hand,” he lamented, “has become more arrogant, annoying, and, above all, planned”. He went on to write about the infiltration of moscow agents into the documentation of emigrant organizations and the theft of lists with the addresses of Ukrainians. He pointed out that after this, there were more frequent cases of letters from relatives or even unknown persons urging them to return to the ussr. “Among Ukrainians,” Rebet wrote, “there appeared leaflets signed by the fictitious bolshevik organization “Dnipro” (bolsheviks use a similar practice with other peoples, in particular the Baltic ones). These leaflets show how quickly the moscow sabotage apparatus reacts to events in the lives of emigrants” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10901. – Vol. 1. – P. 61–64).

In one of its regular issues, “Ukrainskyi Samostiynyk” returned to this topic. It discussed the leaflets and questionnaires from the “Dnipro” group that Ukrainians received in the mail. They were brought to the newspaper as evidence of interference in private life. The leaflets invited people to join the group and, as a sign of agreement, to make certain marks in restaurants, cinemas, and churches. The people who brought them to the editorial office were outraged, alarmed, and frightened.

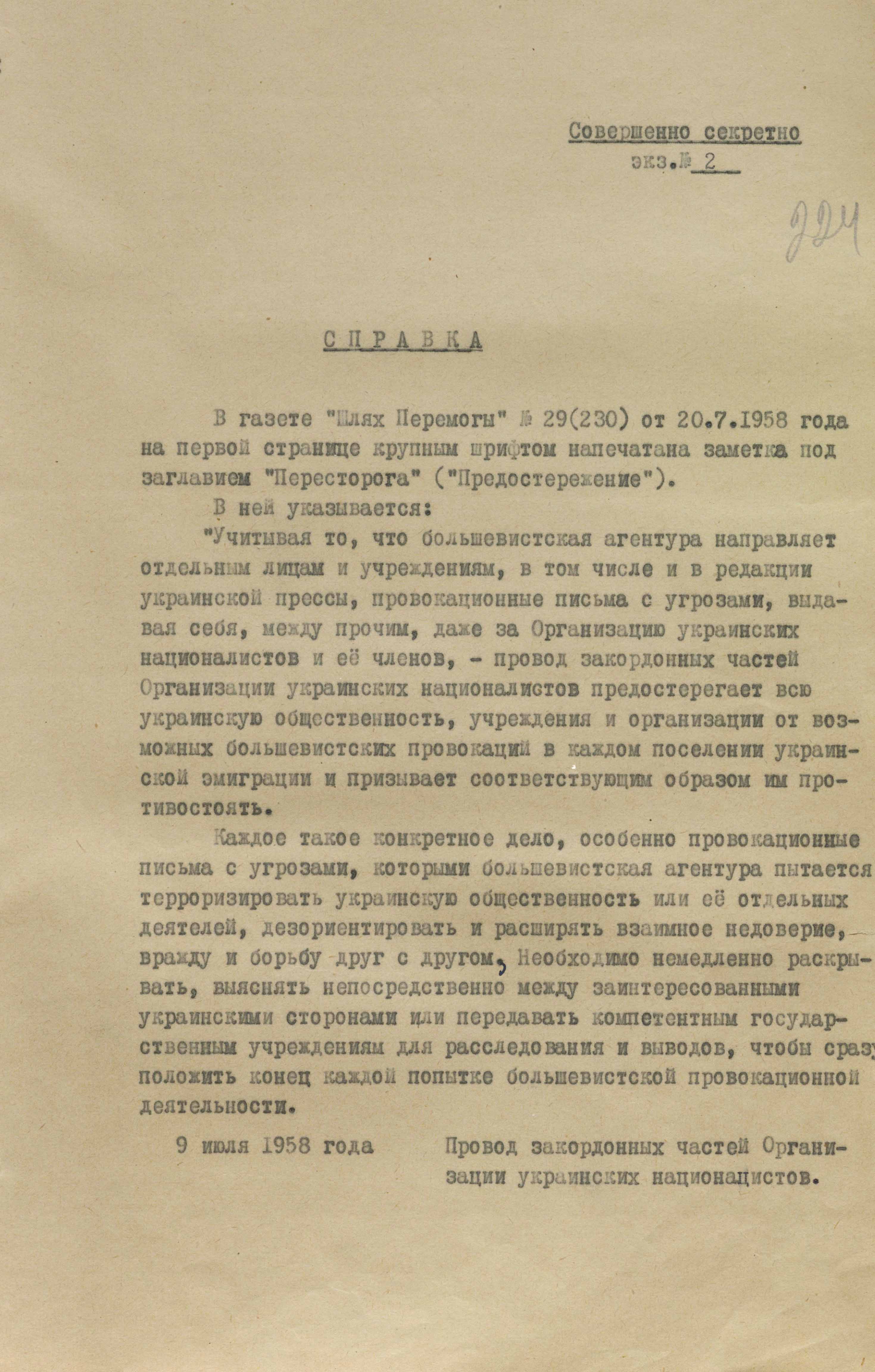

Therefore, the leaders of the Ukrainian emigration continued to try to debunk the activities of the “Dnipro” group at the pages of the newspaper. They wrote openly that the kgb was behind this, in particular its branch in East Germany. “We should remember,” said one of the regular publications, “that a rather formidable enemy apparatus is working to dismantle the emigration, constantly racking its brains over how, where, and when to strike our community”. (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10901. – Vol. 1. – P. 109).

The article emphasized that the kgb, through the “Dnipro” group and the “committee for return to the Motherland”, was purposefully carrying out measures against all sorts of Ukrainian political organizations abroad. For each one, they would choose specific tactical approaches and act in such a way as to cause discord among them, forcing them to accuse each other. Therefore, they called for unity in repelling such attacks, for solidarity, so as not to confuse personal and political interests with those of Ukraine as a whole.

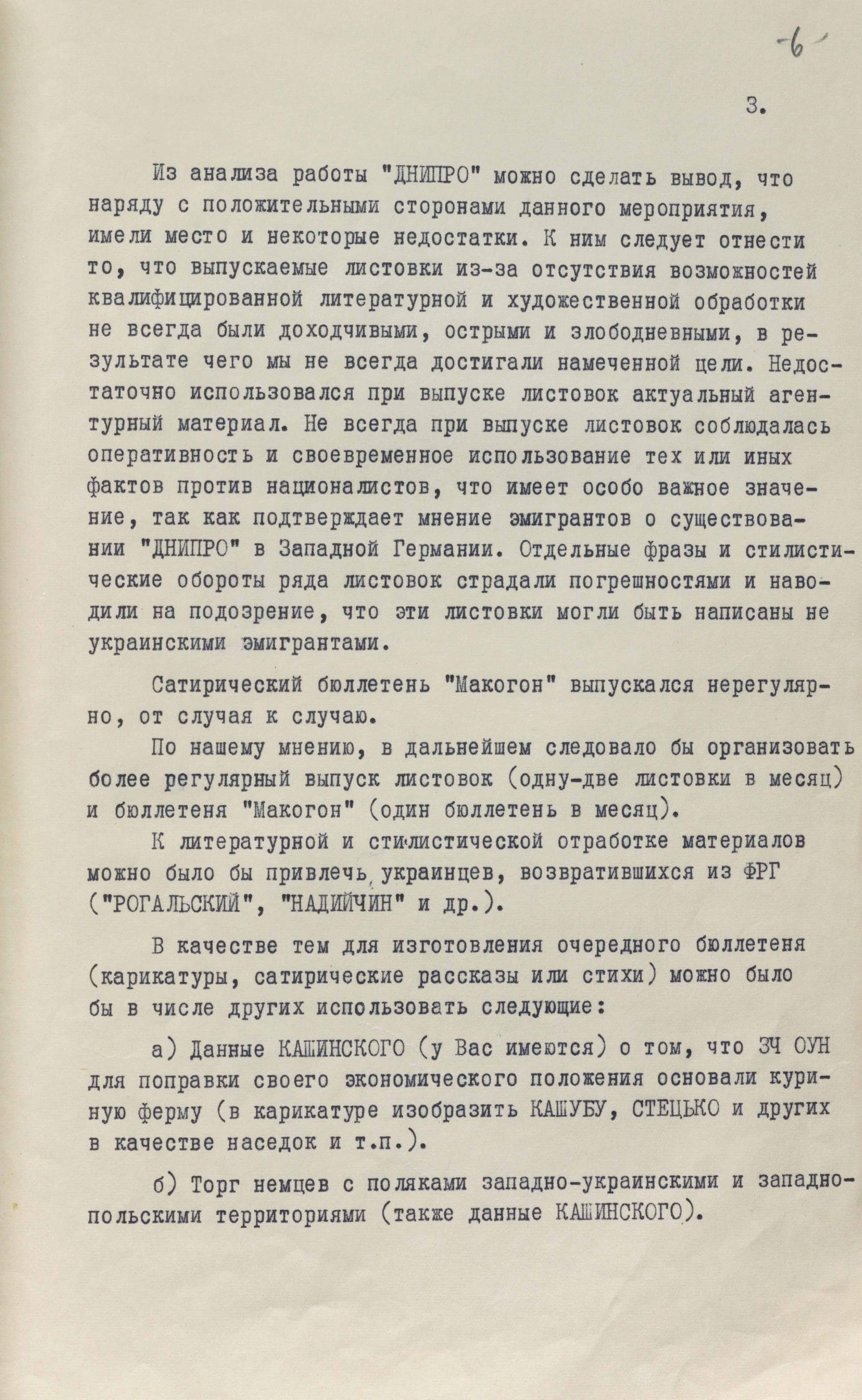

Despite the emigration community’s exposure of the true nature of the “Dnipro” group, the kgb did not cease its activities. Instead, operational plans set the task of producing leaflets at least once or twice a month and studying the issue of their distribution in France, Belgium, and other European countries. As for the content, kgb curators from moscow recommended presenting as many sub-truths from the life of emigrants as possible, and diluting real events with all sorts of fabrications and assumptions which would distract Ukrainians from organizational matters and encourage them to sort out their relationships with each other.

To this end, the kgb prepared and distributed a leaflet about the alleged mysterious murder of writer viktor petrov abroad by Bandera’s followers for speaking out against them. In 1959, immediately after the kgb operation to assassinate S. Bandera, the first leaflet appeared on behalf of the “Dnipro” group stating that it was suicide, while another claimed that people from his inner circle were involved in the OUN leader’s death and were trying to take over his position.

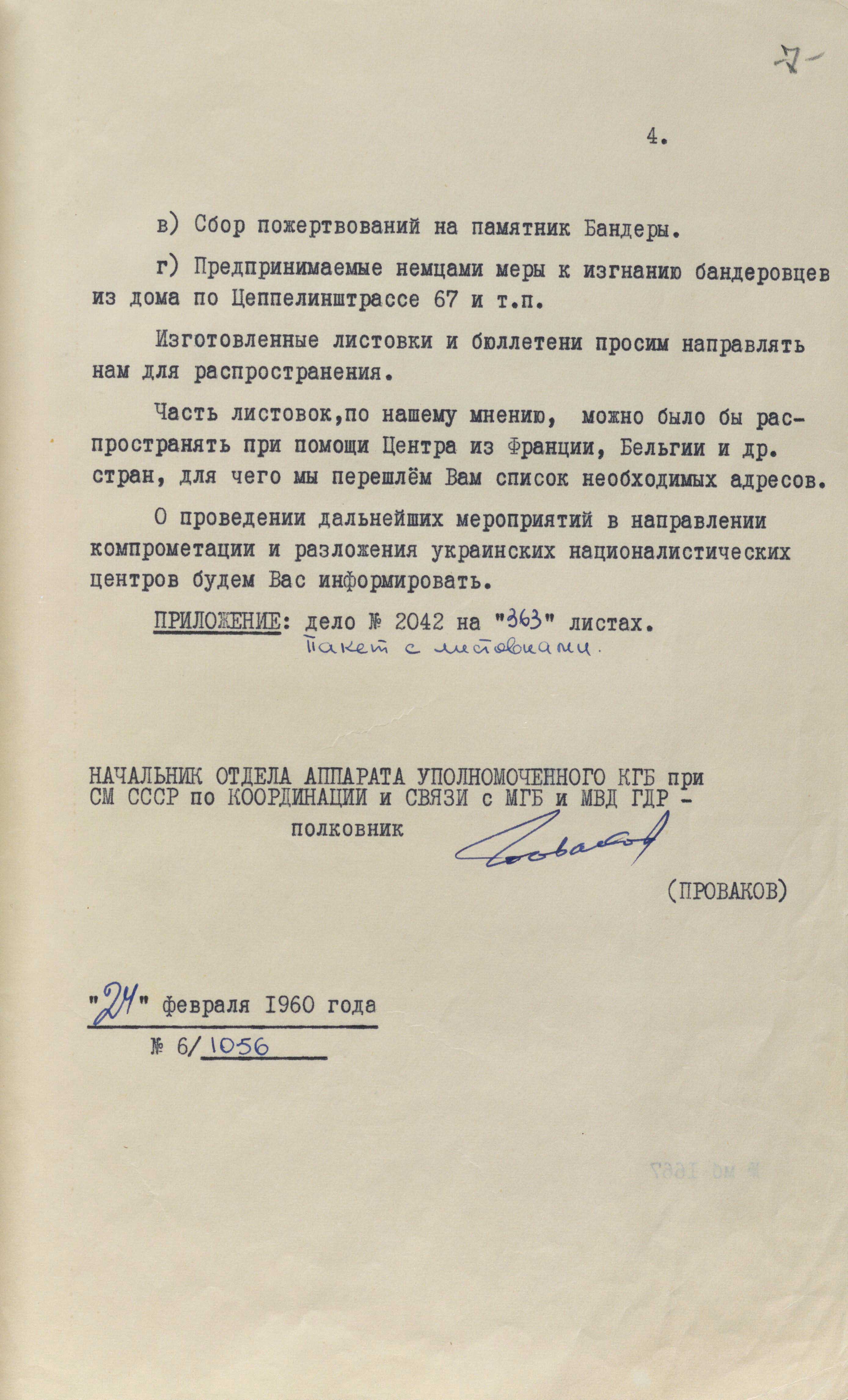

According to archive documents, within 6 years, about 60 leaflets were prepared on behalf of the “Dnipro” group, along with a bunch of different bulletins. In December 1962, the kgb issued a resolution stating: “In connection with the change in the operational situation in the FRG, the continued existence of the legendary organization “Dnipro” is considered inappropriate, and a decision has been made to continue working to undermine emigration by other means.” (FISU – F. 1. – Case 10901. – Vol. 2. – P.114).

This special operation by the kgb is further evidence that, on the kremlin’s orders, a systemic, long-term, and multi-level information war was waged against Ukrainian political émigrés, using a variety of specific practices. The main methods included misleading the audience, using disinformation and compromising information, discrediting leaders, sowing mistrust and suspicion among Ukrainians, and creating divisions within the émigré community. In fact, it was a kind of prototype of the modern hybrid operations that moscow has developed and carried out against Ukrainians around the world in different historical periods.