Minister of Railways of the Ukrainian People’s Republic Serhii Tymoshenko and His Illegal Trip to Kharkiv

6/18/2025

The case against Serhii Tymoshenko, a former Minister in governments of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, was given the operational name “Putieiets” (“Railwayman”– Transl.) by the сhekists. He was well aware of the network of transportation routes in the Ukrainian ssr, and this made him a dangerous enemy of the soviet government in case of a resumed struggle for Ukraine’s independence. He proved this knowledge in practice, having managed to illegally come from abroad to Kharkiv for a secret meeting. This story from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine has never been mentioned in any biographical materials, memoirs, or publications.

The gpu of the Ukrainian ssr showed operational interest in the personality of Serhii Prokopovych Tymoshenko in the early 1930s. At that time, he lived in Lutsk, holding the position of chief architect of agricultural construction in Volyn, and designing churches and all sorts of agricultural facilities. At the same time, he was actively involved in public and political activities, and at different times was elected Ambassador (MP – Transl.) from Volyn to the Polish Sejm and Senate. In 1931, he became the Chairman of the Council of the Lutsk Brotherhood of the Holy Cross and headed the Metropolitan Petro Mohyla Society of Supporters of Orthodox Education and Protection of the Traditions of the Orthodox Faith. In 1933, he was Deputy Chairman of the Volyn Public Committee to Help the Starving in Soviet Ukraine.

But even this was not the only thing that worried the chekists. One of the documents states that S. Tymoshenko in Lutsk “led the Lutsk Intelligence Center, known for its active insurgency and sabotage activities in the territory of the ussr”. This was an Intelligence Center that was subordinated to the special service of the Ministry of Military Affairs of the State Center of the UPR in exile. S. Tymoshenko was one of its leaders. This made him a dangerous enemy of the soviet government. Therefore, they began to collect case file on him.

The documents collected at different times by the gpu/nkvd of the Ukrainian ssr on S. Tymoshenko allow us to trace the life of this extraordinary personality only in fragments. They state that he was born on February 5 in the village of Bazylivka (now Konotop district, Sumy region). He had two brothers. It was reported about his older brother Stepan that in 1921 he moved with his family to the United States, where he worked as a Professor at a university in California. His younger brother Volodymyr also lived in the United States and was a Professor of political economy.

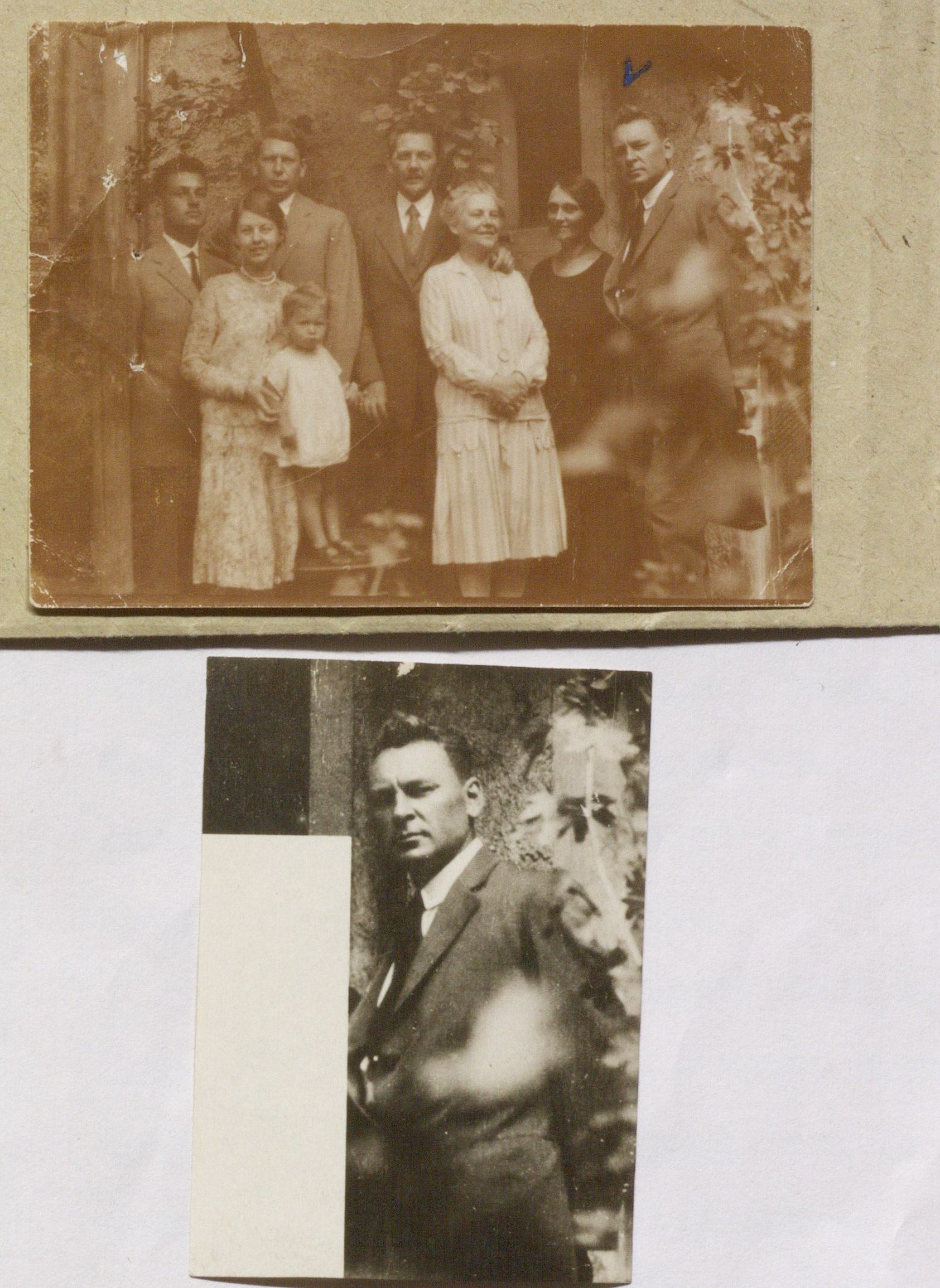

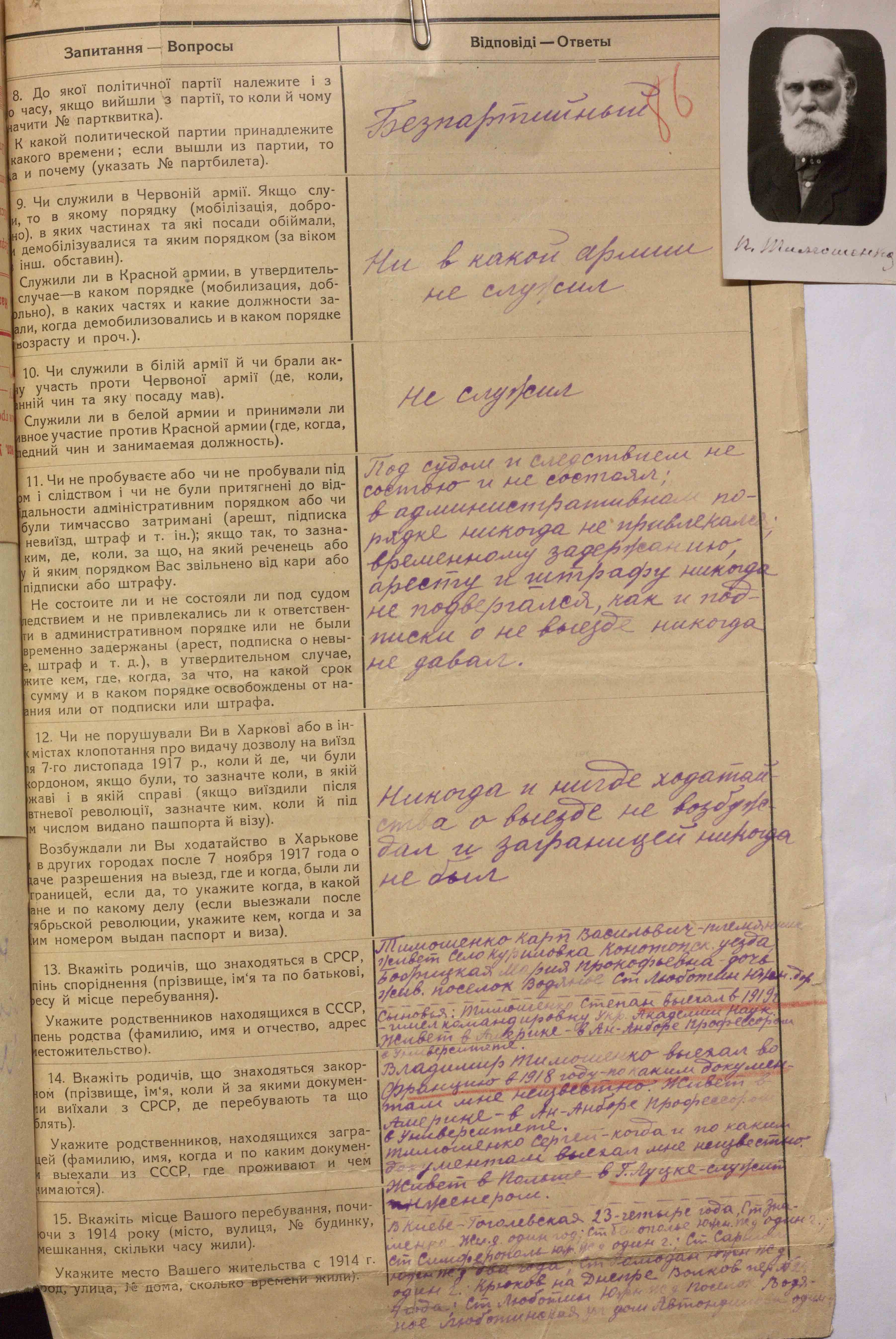

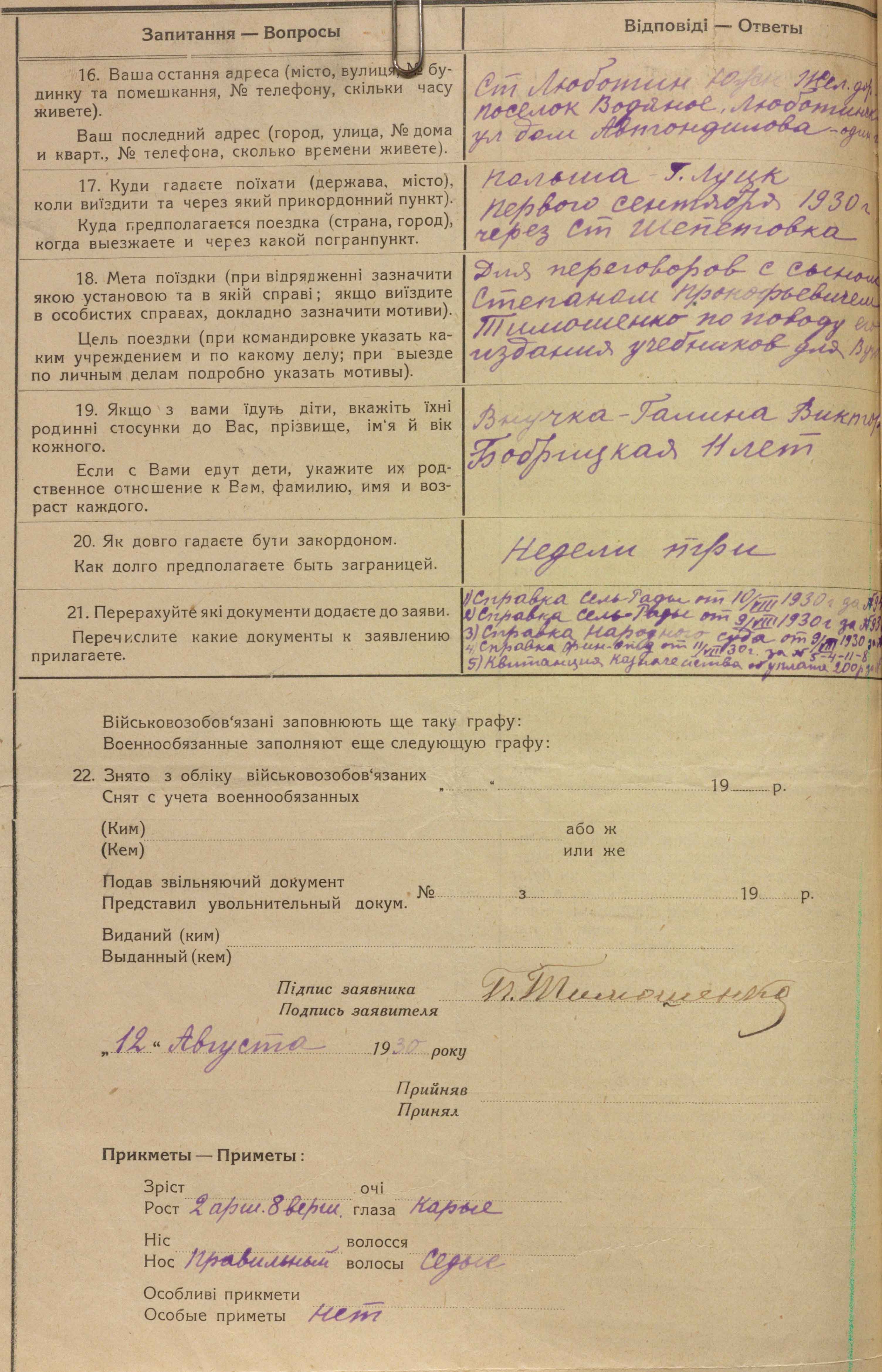

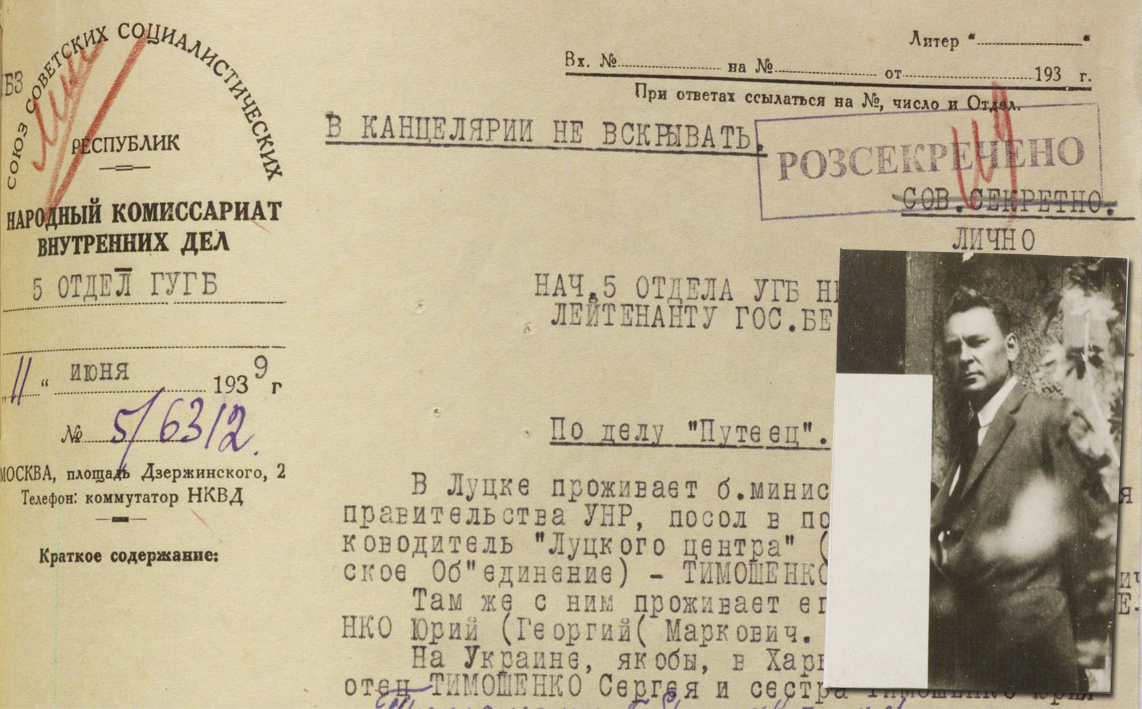

According to archival documents, the chekists tracked down Tymoshenko’s father, Prokip Tymofiyovych. They found out that he had applied to the soviet authorities for permission to travel abroad to visit his sons, but was denied every time. The case file includes a questionnaire and a photo of his father, as well as of Serhii himself in a group photo.

The chekists did not study Tymoshenko’s biography during the Ukrainian People’s Republic too deeply. They just mentioned that he was Minister of Railways in a few UPR governments and had extensive contacts among Ukrainian figures. It is known from open sources that he did not take this position by chance and left a significant mark on Ukrainian history and the liberation movement for independence. Having graduated from the Romny Real School, he entered the St. Petersburg Institute of Civil Engineers. In St. Petersburg, he joined illegal Ukrainian organizations, was an active member of the Ukrainian student community, and started an underground group of students studying Ukrainian architecture.

After graduation, he served in the railway department in Kovel, Kyiv, and Kharkiv. His sketches were used to build houses and departmental buildings in those and other cities, including the North-Donetsk Railway Administration, a complex of 19 railway stations and other buildings on the Kuban-Black Sea Cossack Railway, and much more. He tried to develop architectural projects in the Ukrainian Art Nouveau style.

During the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917-1921, Tymoshenko became one of the leading figures in Slobozhanshchyna, was appointed Provincial Commissioner of Kharkiv province, was elected a member of the Central Rada, Chairman of the Peasant Congress of Sloboda Ukraine, and headed the Ministry of Railways in the governments of Isaac Mazepa, Vyacheslav Prokopovych, and Andriy Livytskyi. He participated in the Second Winter Campaign of the UPR Army and was awarded the Cross of Symon Petliura.

After the defeat of the national liberation struggle, Serhii Tymoshenko lived and worked in Lviv, where he participated in designing and constructing churches, museums, and residential buildings. In 1924-1929, he moved with his family to Czechoslovakia. At first he taught architecture and agricultural construction at the Ukrainian Economic Academy in Poděbrady, and soon became a Professor, the Dean of the Engineering Faculty, and later – the Rector of the Academy. In 1930, he moved to Lutsk, where, according to archival documents, along with his professional work, he became involved in social and political, and even illegal, activities as part of the struggle to restore Ukraine’s independence.

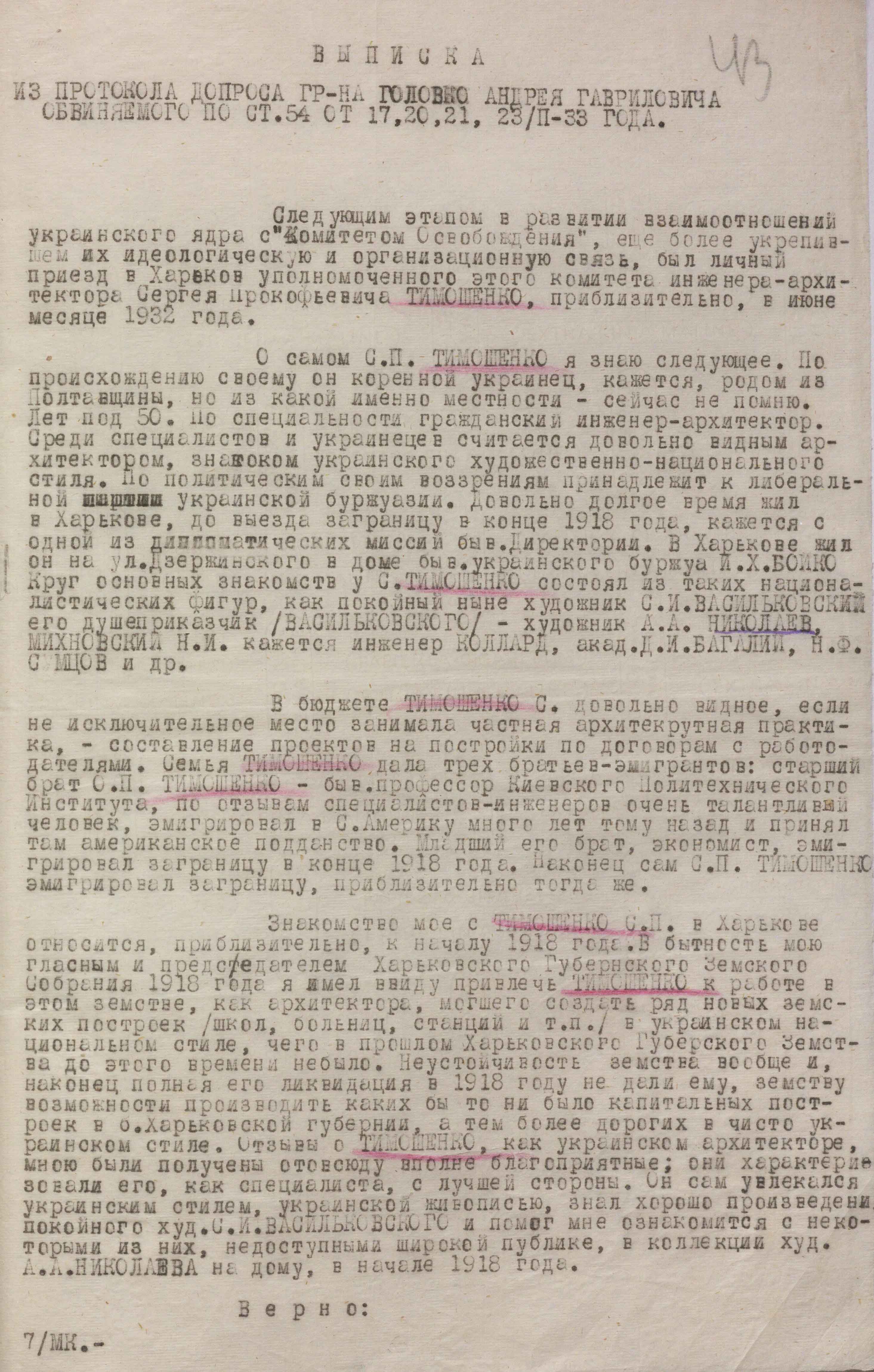

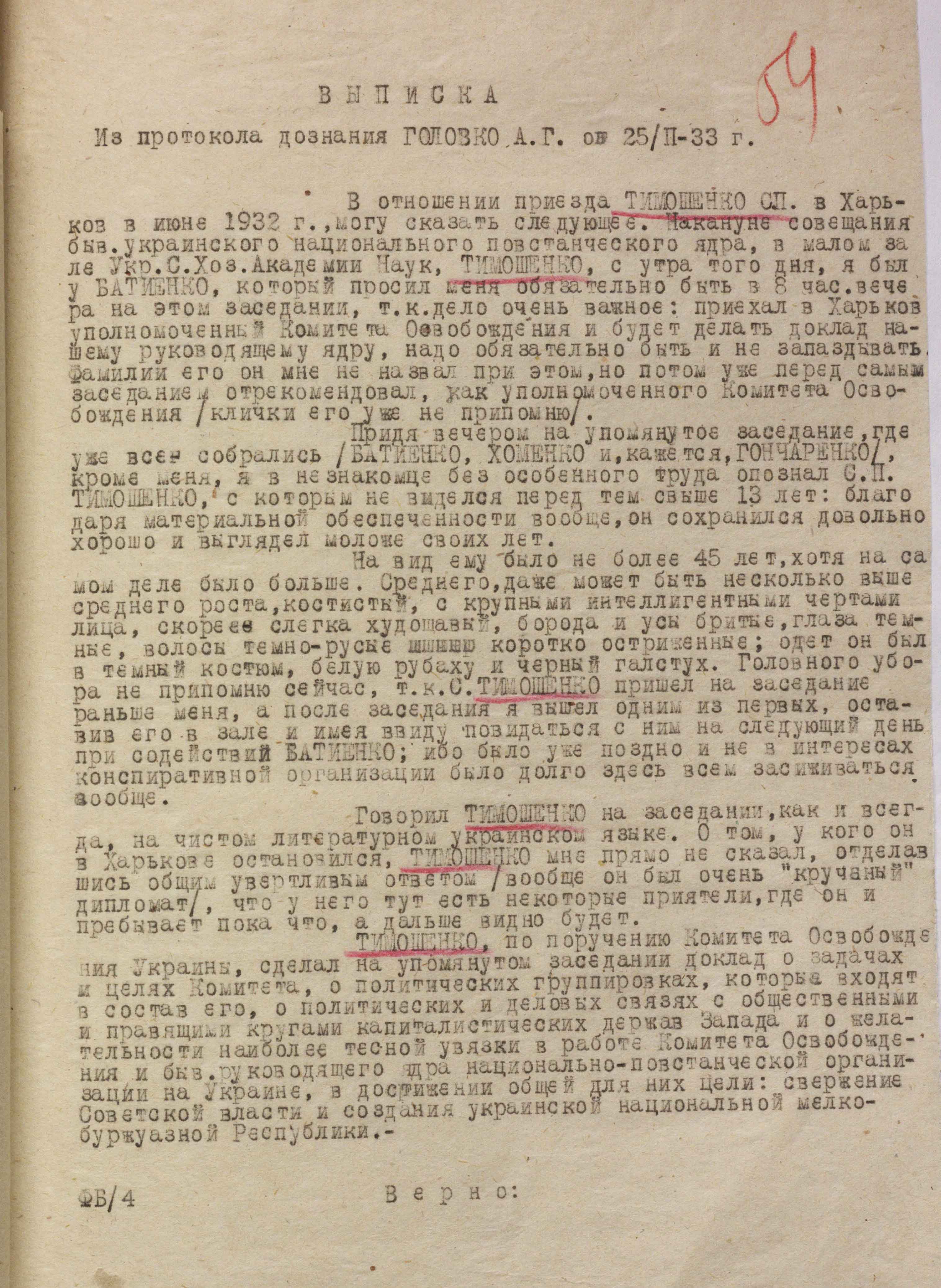

The case file includes protocols of interrogation of Andrii Havrylovych Holovko, former Chairman of the Kharkiv Zemstvo Provincial Assembly (1918), who was arrested by the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr in January 1933 and executed in March of that year for counterrevolutionary espionage and sabotage in agriculture. During the interrogation, A. Holovko testified about S. Tymoshenko’s illegal arrival under a different name in Kharkiv in June 1932 to hold a secret meeting. According to the interrogation protocols, he knew S. Tymoshenko well from their previous work together in Kharkiv. He testified about him as follows:

“...Among specialists and Ukrainians, he is considered a fairly well-known architect, an expert in the Ukrainian artistic and national style. According to his political views, he belongs to the liberal Ukrainian bourgeoisie... In Kharkiv, he lived in the house of the former Ukrainian bourgeois I. H. Boyko in Dzerzhynskyi Street. S. Tymoshenko’s circle of main acquaintances consisted of such nationalists as the late artist S. I. Vasylkivskyi, his (Vasylkivsky’s) manager –artist O. O. Nikolaiev, M.I. Mikhnovskyi, engineer Kollard, Academician D. I. Bahalii, M. F. Sumtsov, and others... Everywhere I heard only positive words about Tymoshenko as a Ukrainian architect; he was characterized as a professional in the best possible way. He was fond of the Ukrainian style, Ukrainian painting, knew well the works of the late artist S. I. Vasylkivskyi and helped me to see some of them, which were not available to the general public...”

(FISU. – F.1. – Case 7166. – Vol. 1. – P. 43).

He said that his meeting with S. Tymoshenko took place in June 1932. He was asked to come to the small hall of the Ukrainian Academy of Agricultural Sciences in the evening. There was allegedly a meeting of “members of the leading national-insurgent link of Ukraine, who saw the overthrow of soviet power and the creation of a Ukrainian national petty-bourgeois republic as the main task of their activities”. Obviously, A. Holovko wrote these and other phrases and testimonies for the interrogation report under the dictation of the chekists.

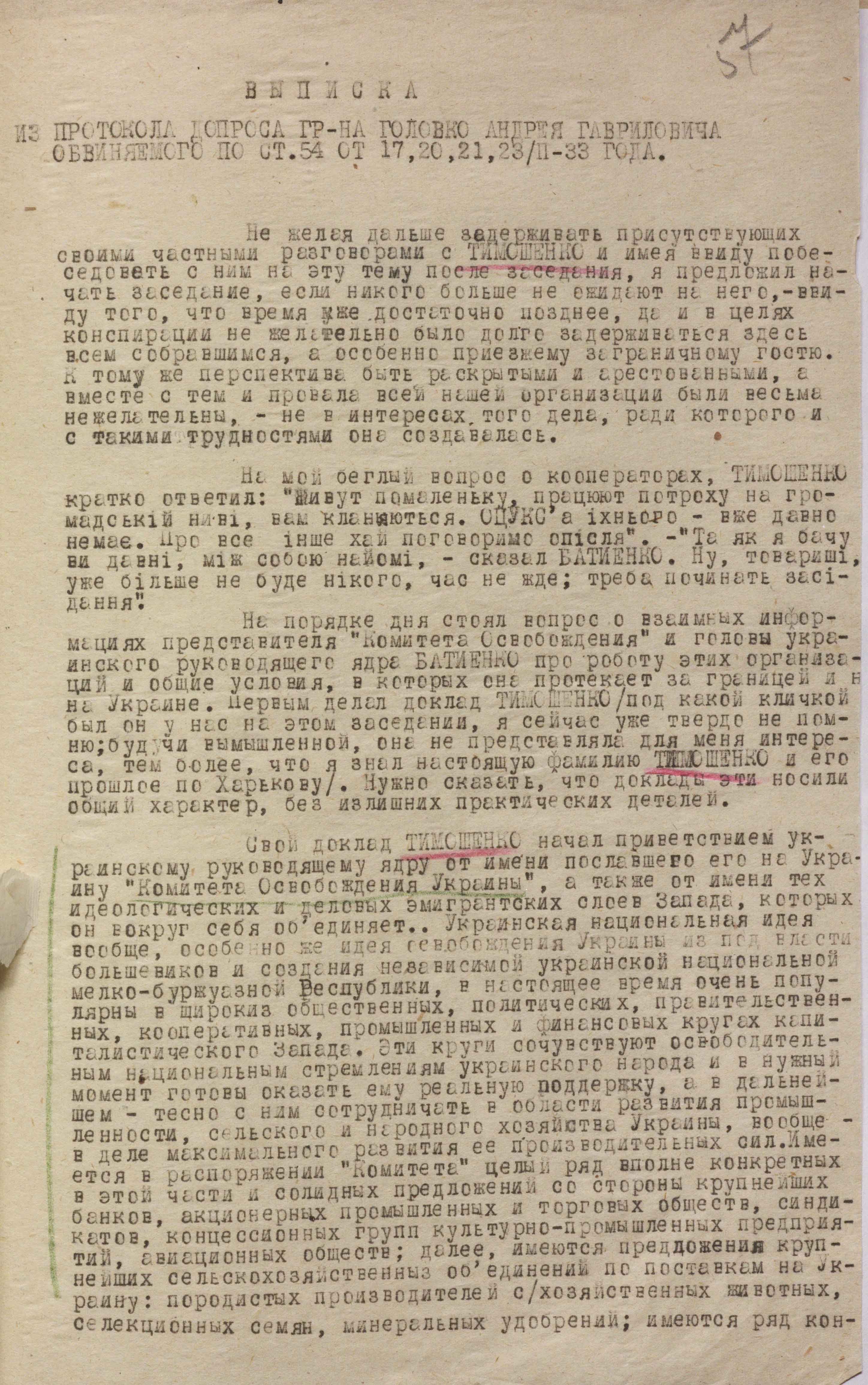

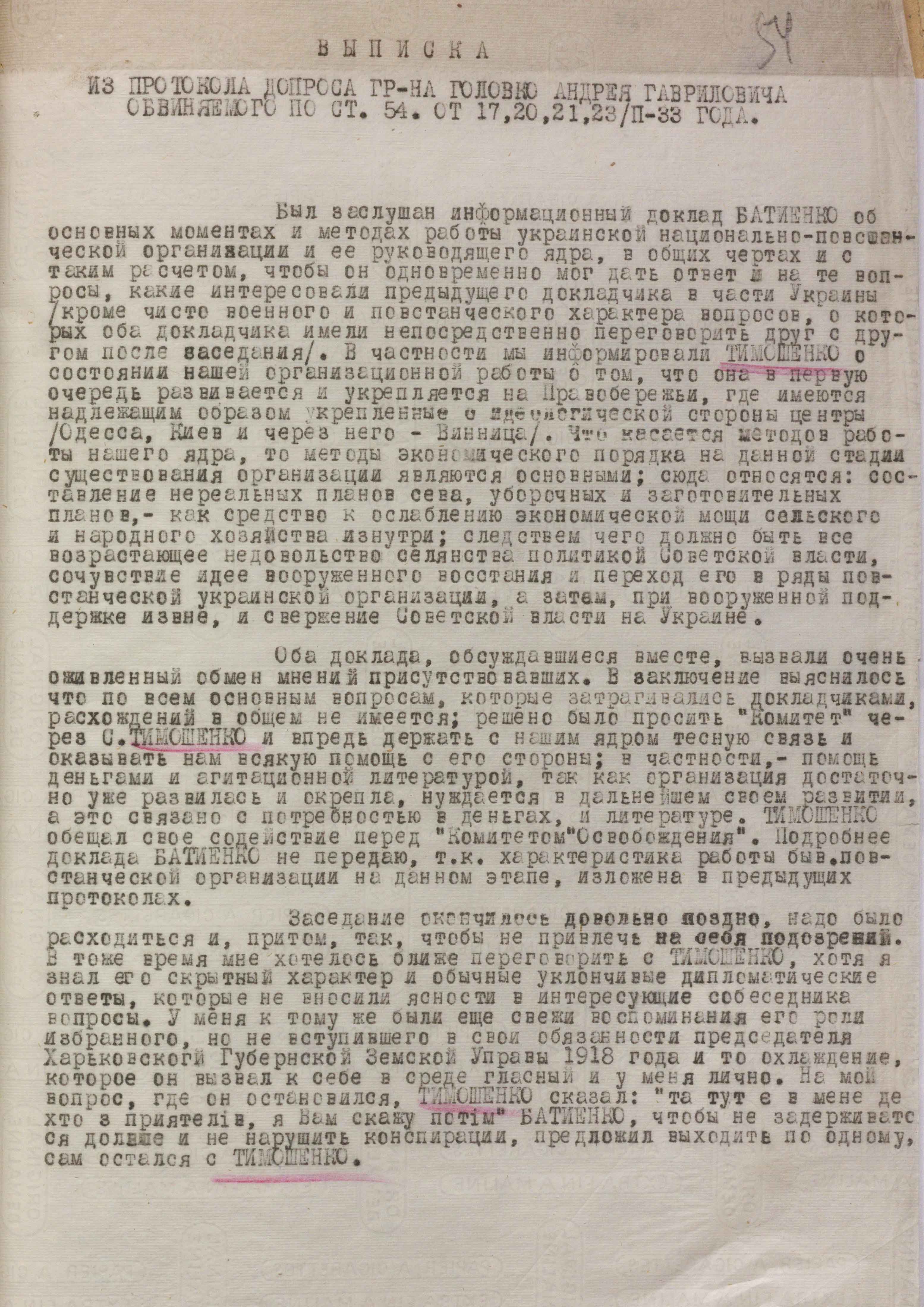

In particular, he referred to S. Tymoshenko as an authorized representative of the “Committee for the Liberation of Ukraine” who secretly arrived in Kharkiv to participate in the meeting and stayed with his friends, but did not say with whom exactly. The meeting discussed the situation in soviet Ukraine, a plan for further joint actions, the provision of material assistance, ways to obtain weapons, and other issues. A. Holovko recounted Tymoshenko’s speech at the meeting. However, the phrases from the interrogation report are similar to most of the testimonies of people repressed at the time in Kharkiv region and other regions of soviet Ukraine.

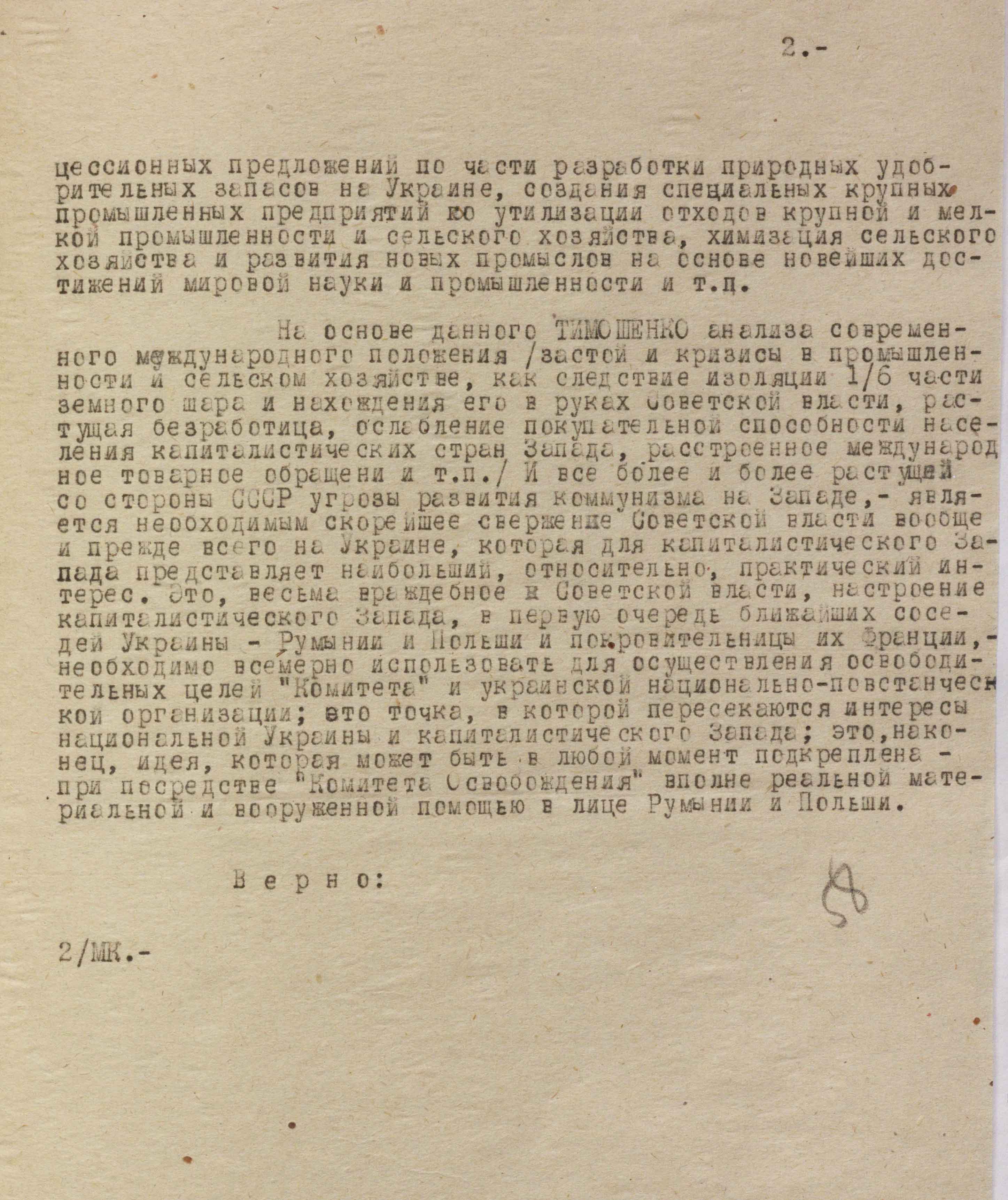

“The Ukrainian national idea in general,” Tymoshenko allegedly said, “and especially the idea of liberating Ukraine from the bolshevik rule and creating an independent Ukrainian national petty-bourgeois republic is now very popular in the broad public, political, governmental, cooperative, industrial and financial circles of the capitalist West. These circles sympathize with the liberation national aspirations of the Ukrainian people and are ready to provide them with real support at the right time, and in the future to cooperate closely with them in the development of industry, agriculture and the national economy of Ukraine, and in general in the maximum development of its productive forces. The “Committee” has a number of quite specific and solid proposals from large banks, joint-stock industrial and commercial companies, syndicates, concession groups, cultural and industrial enterprises, aviation companies; there are also proposals from large agricultural associations to supply Ukraine with good breeds of farm animals, breeder seeds, mineral fertilizers; there are numerous concession proposals for the development of natural resources in Ukraine, the creation of large industrial enterprises with utilization of industrial and agricultural waste, chemicalization of agriculture and development of new industries based on the latest achievements of world science and industry...”

(FISU. – F.1. – Case 7166. – Vol. 1. – P. 57-58).

Such testimonies must have been produced by the chekists as part of a large-scale campaign to expose the so-called underground anti-soviet organizations, the existence of which was invented or artificially created in order to arrest maximum of people who disagreed with the communist party’s policies under this pretext. That was a period of a new wave of repression and artificially created famine in villages. In 1932, a special resolution of the politburo of the central committee of the cpsu was issued, which instructed the chief of the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr Stanislav Redens, together with the secretary general of the communist party(of bolsheviks) of Ukraine Stanislav Kosior, to “develop a special operational plan for the liquidation of the main kulak and Petliura counterrevolutionary ”nests”. At the same time, the “Operational Order of the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr No. 1” was issued, in which the chekists were assigned “the main and most important task of an urgent breakthrough, exposure and defeat of the counter-revolutionary insurgent underground and the task of a decisive blow against all counter-revolutionary kulak-Petliura elements that actively counteract and disrupt the main measures of the soviet government and the party in villages”. The underground organization, the “Committee for the Liberation of Ukraine”, was liquidated by the gpu back in 1929. The trial of members of the mythical “counter-revolutionary organization” “SVU” (“Spilka Vyzvolennia Ukrainy” – “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine”– Transl.), which allegedly existed in the Ukrainian ssr since 1926 and united anti-soviet intellectuals, took place in 1930. By fabricating new cases and trying to revive the non-existent “Committee for the Liberation of Ukraine”, the chekists were preparing the ground for the subsequent total pogroms that were launched en masse in 1932-1933, when stalin decided to finally put an end to “Ukrainization.”

Information about Tymoshenko’s visit to Kharkiv and his participation in a secret meeting was extracted by the chekists from A. Holovko and some other city residents in February 1933, eight months after the event. All of this gives reason to question some of the facts and details. S. Tymoshenko’s secret arrival and his meeting with a certain circle of people he trusted could well have taken place. He had a lot of unfinished business in the city and personal drawings and manuscripts that he would have preferred to find and take with him. As his fellow emigrants recalled, back in 1921, after a search of his apartment, the chekists took away everything related to his design bureau-workshop in two trucks, along with the archives, which contained all copies of projects and other important documentation. Among them, there were all the works in the Ukrainian architectural style.

There is no information in the case file about the details of Tymoshenko’s stay in Kharkiv. For some time, he fell off the radar of the chekists, but his operational cultivation did not stop. A document dated October 1935 states that as a former Minister of Railways of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, he might have had long-standing good connections among railway employees whom he could have involved in counterrevolutionary and sabotage activities. “In this connection,” it was noted, “it is necessary to thoroughly identify and cultivate all the persons who know him. This work should be carried out with extreme caution, since we are doing a very important work around Tymoshenko abroad” (FISU. – F.1. – Case 7166. – Vol. 1. – P. 98).

Operational cultivation was intensified in the second half of the 1930s, when he became an Ambassador to the Polish Sejm. In 1939, a document was sent to Kyiv from moscow, which contained a cryptic phrase about an “important work abroad”. It read as follows: “For several years now, the issue of recruiting Serhii Tymoshenko has been studied, but it has not been resolved yet. Given Tymoshenko’s extremely important role in the Ukrainian nationalist movement in Volyn, his great authority (he was re-elected Ambassador to the Polish Sejm in the last election), we consider recruiting Tymoshenko to be one of our most important tasks. Please collect all information about Tymoshenko’s family and other ties in Ukraine” (FISU.– F.1. – Case 7166. – Vol. 1. – P. 119).

According to declassified documents, while the chekists were collecting information on close relatives, World War II broke out. There was an opportunity to look for S. Tymoshenko in Lutsk, which had already been occupied by the Red Army units and which, along with all western Ukrainian lands, was part of the Ukrainian ssr. But he was not found in the city. Then they sent an orientation to all the local nkvd units, and searched for him in belarus. This continued in the following years. All in vain.

Meanwhile, S. Tymoshenko managed to leave the country in time. He lived and worked as an engineer in Warsaw, Lublin, Prague, and other cities. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, he found himself in a camp for displaced persons. Only his pre-war Polish citizenship saved him from extradition to the soviet authorities. In 1946, with the assistance of his younger brother Volodymyr, he emigrated to the United States. He spent the last years of his life in Palo-Alto, California. There he designed several churches and other buildings for the Ukrainian community in Canada, Argentina, Paraguay, and the United States. In total, he left behind a rich creative heritage – more than 400 different buildings and architectural complexes. He is the author of the tombstone on Symon Petliura’s grave in Paris.

S. Tymoshenko passed away on July 6, 1950, without leaving written memoirs about some of the secret aspects of his participation in the struggle to restore Ukraine’s independence. Streets in Konotop, Kovel, Lutsk, and Lviv are named after him. A memorial plaque in Kharkiv reads that “Serhiy Tymoshenko, an outstanding architect, one of the creators of Ukrainian architectural modernism, Minister of Railways of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, Rector of the Ukrainian Economic Academy, and Senator of Rzeczpospolita, lived in this house”.