Operation “Stavka”. Unknown Documents on the Murder in Rotterdam

5/29/2025

Operation “Stavka”. Unknown Documents on the Murder in Rotterdam

On May 23, 1938, in Rotterdam, Pavlo Sudoplatov, an officer of the ussr nkvd, on stalin’s instructions, assassinated OUN leader Yevhen Konovalets. New documents from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine shed light on some unknown episodes of that operation and provide answers to the question of whether top OUN leaders suspected that P. Sudoplatov and agent “Lebed” were not in their midst by chance, but acted on the instructions of the nkvd, how they were checked, what the OUN leader wanted to hear most from the “fugitives” from soviet Ukraine, why stalin insisted on Yevhen Konovalets’ assassination, and why Konovalets did not want stalin to be killed, and more.

Vasyl Khomyak–“Lebed”. The Check Had Been Passed

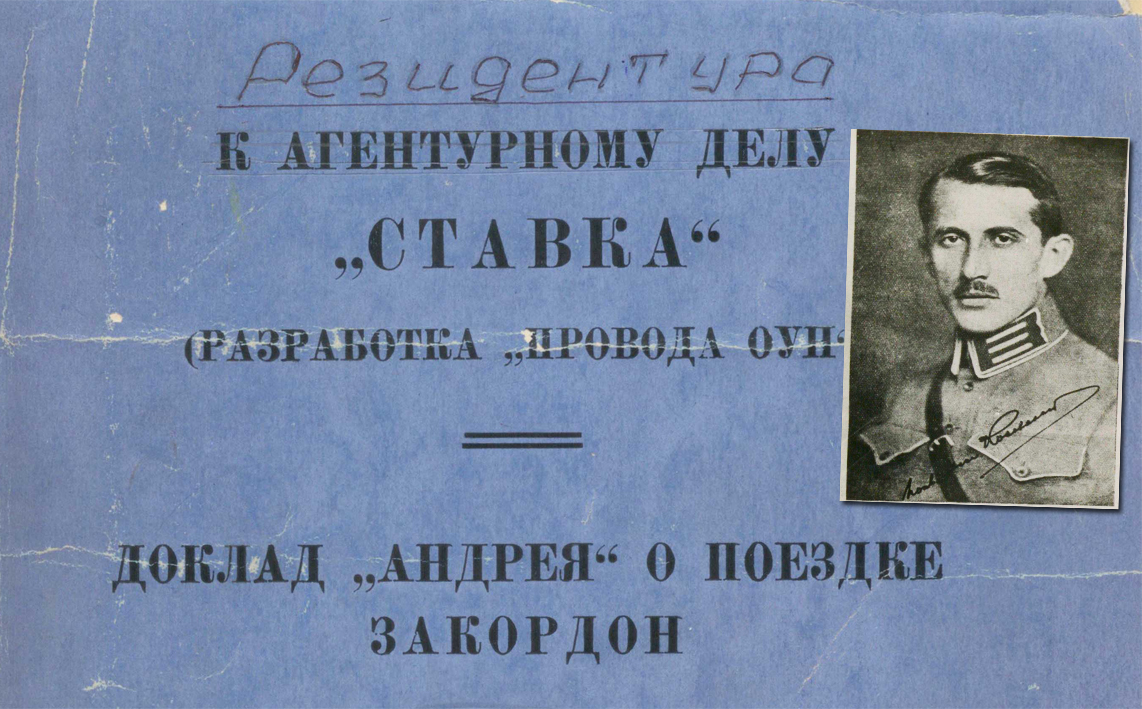

In August 1933, under the guise of a refugee from soviet Ukraine, the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr sent an agent “Lebed” abroad. He was tasked with infiltrating the OUN leadership, in particular the inner circle of Yevhen Konovalets. Some of the details of that operation and the identity of Vasyl Khomyak (“Lebed”) were described earlier on the basis of his declassified agent case file from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine. The new documents from the case code-named “Residentura “Stavka” confirm the already known facts, and also significantly supplement and specify a number of episodes related to the planning of Yevhen Konovalets’ assassination by the gpu/nkvd.

In the years of WWI Vasyl Khomyak served in the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen units of the Austro-Hungarian Army. He commanded a chota, and one of his subordinates was Andrii Melnyk. Then he was taken prisoner of war by the russians and from 1916 to 1918 was held in a prisoner of war camp in Mariupol. During the national liberation struggle, he showed up in Kyiv, where A. Melnyk introduced him to Ye. Konovalets. They fought together against units of the red army and other enemies of the UPR. After the Ukrainian Army had retreated to Poland and stopped armed resistance, Konovalets sent loyal comrades-in-arms to soviet Ukraine to organize underground centres and insurgency. One of those was V. Khomyak. He was smuggled across the border by Sotnyk Roman Sushko. But V. Khomyak failed to start underground work. In 1921, he fell into the hands of the chekists, was recruited and used in the operational cultivation of Ukrainian insurgent organizations.

Soon, a plan to infiltrate Khomyak into the OUN leadership was hatched in the bowels of the Ukrainian SSR. The direct implementation of the operation began in August 1933, when he arrived in Belgium on a soviet cargo ship and asked the local authorities for political asylum and assistance in getting to Prague.

The case file “Residentura “Stavka” contains photographs, diagrams, personal documents, as well as materials that contain information on how and why the organs of the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr chose Khomyak as a candidate for infiltration into the OUN leadership, how they prepared and took him abroad, what tasks they set at each stage, how they chose methods of communication, organized meetings with representatives of the residentura abroad, and provided funding. In particular, it is said that instead of currency, he was given gold jewelry, which included a man’s watch with a chain, a woman’s watch, a cigarette case, coins, diamond earrings and “a gold ring with a good, clear diamond of several carats”. But immediately after arriving in the Belgian city of Ghent, he found out that local banks and jewelers refused to buy russian gold and exchange it for francs. That was the first problem.

The circumstances of V. Khomyak's first meeting abroad with E. Konovalets and other leading OUN leaders, their reaction to his “escape” from the ussr, and the doubts they had about him are described in detail. This information is reflected in his report after his return from abroad a year later.

According to Khomyak’s testimony, the government of Ghent could not provide him with the necessary documents and travel permits, but instead advised him to address the relevant institutions in Brussels. There, an employee of one of the canteens, when she learned that he was a refugee from Ukraine, gave him the address of Dmytro Andriyevskyi and introduced him as a representative of the Ukrainian community. Dmytro Andriyevskyi was a member of the Provid of Ukrainian Nationalists and was in charge of organizational matters related to the OUN’s activities abroad. He immediately became interested in the “fugitive” and began to ask questions. When he found out that he personally knew A. Melnyk, Y. Konovalets, and R. Sushko, his interest increased.

D. Andriyevskyi informed Y. Konovalets and R. Sushko about the stranger by letter. In the meantime, he organized a meeting with Mykola Stsiborskyi, Deputy Head of the Provid of Ukrainian Nationalists and a member of the Provid Makar Kushnir, whom he introduced as Bohush. At the time, they were in Brussels on some business. Bohusz immediately recognized the guest and recalled that in 1918, when the Central Rada, of which he was then a member, evacuated from Kyiv to Zhytomyr, they were traveling in the same carriage.

After reminiscing about those events and mutual acquaintances, V. Khomyak was asked in more detail about the state of affairs in soviet Ukraine in various spheres of life, about people’s moods, attitude to the soviet power, and the activities of the Ukrainian emigration. This went on until two in the morning. In the following days, they continued the same communication, and two weeks later they arranged a “surprise”. They brought him to the apartment where M. Stsiborskyi was staying and led him into a room with tightly curtained windows. According to V. Khomyak, in the corner he saw a man whose face was obscured. He could not understand who it was. When the man stood up to meet him, he immediately recognized him as Yevhen Konovalets.

In his report, Khomyak emphasized that at that moment he was quite worried, realizing that he was being tested in this way. But everything went well. Konovalets gave him a hug, kissed him, and began to tell the audience how well he knew him. After the emotions had calmed down, the leader of the OUN Provid, in an absolutely different tone, asked Khomyak to tell about everything that happened to him after he was transferred to Ukrainian territory in 1920 to organize underground work. It took six hours to tell the story. The agent had been prepared for such interrogations in advance at the gpu and had a detailed legend to which he adhered.

After that, E. Konovalets additionally asked how Khomyak managed to escape from a bolshevik prison in 1921, about some Ukrainian insurgents who were also arrested by the chekists at that time, and those who managed to escape, in particular, about Osyp Dumin. He asked him what made him flee abroad and why he left his wife and son in the ussr. At the same time, M. Stsiborskyi asked him questions, trying to understand what he had done that prompted him to flee.

After lunch, the conversation continued. “I sat down on the couch with Konovalets”, the report said, “and he again began to ask me some questions that made me feel like he was trying to test me. I answered those questions sometimes calmly, but sometimes with indignation and resentment. Konovalets sensed this and told me that I should not be offended and that I myself should understand the methods the bolsheviks use in their work, and therefore I should not be offended by such questions. He asks me all those questions because he wants to work with me... That if he did not trust me, he would not have visited me. And then he told me that I should know that if it turned out that I had come for some other purpose, I would face severe punishment, despite my past” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 31. – Vol. 4. – P. 690-691).

In his report, Khomyak also wrote about other people’s suspicions that he was an agent of the gpu. However, after a letter from R. Sushko, in which he assured that he did not believe this and vouched for Khomyak, the suspicions disappeared. Then he was introduced to the main documents and plans of the OUN, directions of work, and circulars. In particular, it is said that for three months hetogether with Bohush, on behalf of Ye. Konovalets, had been preparing abstracts for the OUN Congress, so, he made copies of 300 pages and sent them to the gpu through a local resident.

At the same time, as noted in archival documents, an incident occurred with Mykola Stsiborskyi. A soviet representative who called himself Ivan Ivanovych met with him several times. He offered to go to the ussr, to see for himself how well people lived there, and then to debunk everything that the emigrant press wrote about the miserable life, famine, and repression. M. Stsiborskyi told E. Konovalets about those meetings and proposals, and the latter shared the information with some members of the OUN Provid. It was suspected that that was a recruitment attempt that failed. Some linked that extraordinary event and the intensification of the activities of the gpu of the ussr to V. Khomyak’s arrival abroad. In particular, Bohush told him about it. Khomyak pretended to be outraged. After that, Bohush assured him that Yevhen Konovalets and he trusted him, otherwise they would not have let him know.

According to archival documents, after that incident, the OUN Provid decided to intensify its work on conspiracy and to look more closely at everyone in order to timely identify those working for the bolsheviks. But, as shown by the subsequent course of events, the necessary cardinal steps in this direction were not taken.

About What Yevhen Konovalets Asked Most Meticulously

Along with testing Khomiak’s loyalty, Ye. Konovalets asked him lots of other questions. He was interested in the real state of affairs in soviet Ukraine. This knowledge determined which strategic directions and tasks in the OUN’s activities needed to be planned or adjusted first of all.

In his report, V. Khomyak listed the following questions:

“1. What caused the famine in Ukraine and wasn’t the famine deliberately organized by the party and the government to weaken Ukraine in this way, since there is no famine in russia? What about the resistance to collectivization by the peasants and is this resistance spontaneous or can it ever become organized?

2. To what extent are there sabotages in industry and who carries out those sabotages and in what way, i.e. are the sabotages organized or spontaneous?

3. How do I view the situation with the collapse of important industries and what are the views of other people I know in Ukraine, if I have had conversations with them on this matter?

4. Why does no one in Ukraine react in any way to moscow bolshevism’s brutal methods of struggle, why does no one dare to use such a powerful means of struggle as terror, since it cannot be worse than it is, because anyway millions of Ukrainians are dying of hunger, hundreds of thousands are dying in exile, and hundreds of thousands have been shot dead?

5. Who is working in the gpu, i.e. – an ideologically and politically stable element, or perhaps trash of the population, sadists for whom nothing is sacred, and knowing that the worst thing for them is the fall of the existing regime, so they are so brutally fighting all manifestations of the struggle against the existing regime, and who are they by national and social composition?

6. What is the Jewish population of Ukraine’s attitude to Ukrainians’ national struggle, what percentage is supportive, are there Jews who are against the existing regime but for a single russia, but with a different regime, i.e., for the restoration of the old russia?

7. Are there any settled russians in Ukraine who oppose the current regime? Would they take sides or remain neutral in case of an armed struggle against moscow for the liberation of Ukraine?

8. How is the party replenished, with what element – social, national, what is the political level of knowledge of the party masses, what is the strength of their convictions and how loyal is this element to the existing regime in the case of the struggle for the liberation of Ukraine from moscow? Is it possible to expect that some part of the Ukrainians who are current communists can go against moscow if the organization that will lead this struggle has no differences in social issues, but rather sets itself the task of improving this structure, adapting it to the interests of the nation and the Ukrainian independent state?

9. Do young people understand how moscow oppresses Ukraine both, economically and culturally, and are they even aware that this terrible moscow imperialism has been repainted from white to red? How do young people feel about religion, are there any prospects for the spread of religion at all, and what is their spiritual life and moral foundations, and does any morality exist? How to explain the fact that despite the party’s making every effort in the spirit of marxism, materialism, etc., there are still many young people filled with a nationalist spirit?

10. What is the national and social composition of the army, both the command and the soldiers; what are the nationalities of the career officers, border guards, their cultural and living conditions, the general development of the commanding officers, special, military-technical and other units?

11. To what extent is it true that provocation is extremely developed in Ukraine, that people do not trust each other anymore, and how can this be explained?

12. The moods of the workers and peasants and the national composition of the workers.

In addition to the above-mentioned questions, there were others that I cannot recall, as well as questions about Skrypnykism, Shumskism, Khvyliovism, etc.”

(FISU. – F. 1. – Case 31. – V. 4. – P. 431-433).

The gpu thoroughly analyzed these questions and concluded that Ye. Konovalets was quite deeply and substantively interested in soviet reality, focused on sensitive aspects of public life, and was expertly looking for vulnerabilities, and therefore was a dangerous enemy who had to be neutralized at all costs.

Pavel Sudoplatov – “Andrei”. Meetings in Berlin, Vienna and Paris

According to the case file, the OUN leadership, after more than a year of Khomyak’s stay abroad, concluded that it was better for him to return to soviet Ukraine and create an extensive underground organization to participate in the future struggle for independence. In October 1934, he returned to the ussr and reported to the nkvd (by that time already reorganized from the ogpu) that he had fulfilled his task of winning the trust of the OUN leadership. Later, in his letters abroad, he reported on the creation of an underground network and the involvement of dedicated individuals. V. Khomyak himself was allegedly the leader of the “Ukrainian Nationalist Organization”. Among the newly discovered archival documents there are several diagrams of this fictional organization with the names of its members.

All of this was done by the chekists in order, on the one hand, to strengthen the agent’s credibility, and, on the other hand, to distract the OUN forces and pass over false information about the state of affairs on Ukrainian territory. Soon after, the decision was made to introduce a staff member of the nkvd central office into the cultivation of the OUN Provid. Pavel Sudoplatov (operational codename “Andrei”) was chosen for this role. In his letters to Ye. Konovalets, Khomyak said that he had involved his distant relative, whom he had known for a long time, to work in the underground, brought him up in a nationalist spirit, and believed that the young man would make a useful fighter for the idea of Ukraine’s independence.

In July 1935, the two of them crossed the soviet-Finnish border and found themselves in Finland. Soon after, Khomyak returned to the ussr, while his “pupil”, whom the OUN codenamed “Pryimak”, and later “Pavlus”, “Velmud”, “Norman”, and “Valiukh”, stayed abroad. For several months, he was watched, studied, and tested before a decision was made to involve him in the work and initiate him into the most secret aspects of the Organization’s work abroad.

P. Sudoplatov himself partially described the process of his infiltration in his memoirs, which were published in 1997. At the same time, according to different sources and professional studies by Ukrainian historians, that information was somewhat distorted, embellished in some episodes by the author, and generally had a propaganda purpose to discredit the Ukrainian national liberation movement and its leaders. The declassified documents from the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine’s archive, published earlier, made it possible to place certain accents in those memoirs.

Currently, the case file contains P. Sudoplatov’s large memo for the period of his stay abroad in 1935-1936. It was also compiled in the tradition of the Chekist practice of the time, when subordinates tried in every possible way to report to the leadership of the nkvd exactly what it wanted to hear from them and what fit into the overall picture of a decisive struggle against the counterrevolution and implacable enemies of soviet power. For the stalinist regime, these were the Ukrainian nationalists, among whom P. Sudoplatov found himself.

Despite the certain subjectivity of the author’s presentation and assessment of the events of the time, this document, in combination with other evidence, still helps understand how he managed to gain the trust of the members of the OUN Provid, what extremely negative consequences this had for the national liberation movement and its unity in general, and what lessons should be learnt from all that.

P. Sudoplatov wrote that in Finland he was first asked about everything by D. Andriyevskyi. According to him, everything went well, without any suspicions, and he allegedly managed to win favor and trust as a result of the interview. However, it should be borne in mind that D. Andriyevskyi had never been involved in the vetting of outsiders. He was a political referent of the Provid, a good publicist, ideologist, and theorist of Ukrainian nationalism, but not a practitioner of clandestine underground struggle.

Then came a member of the OUN Provid, Omelian Senyk, whom D. Andriyevskyi introduced only by his pseudonyms, “Hrybivskyi” and “Kantsler”. He was more difficult to deal with. P. Sudoplatov characterized him as a cautious and most dangerous person for the nkvd, pointing out: “Hrybivskyi” was always watching very closely not only what I said, but also the expression of my eyes and face, my facial expressions.” In the report, P. Sudoplatov pointed out that O. Senyk allegedly did not like him. Nevertheless, after a series of meetings, OUN leaders decided to leave him abroad to gain experience and prepare for future underground nationalist work.

For six months, P. Sudoplatov lived in Helsingfors (now Helsinki) under the care of the head of the local OUN organization, Kindrat Poluvedko. The latter was an nkvd agent with the pseudonym “Pavel”, but he knew nothing about the true role of the “young member of the underground from Ukraine”.

It was only in January 1936 that P. Sudoplatov was given the necessary documents and sent to Berlin to meet with other leading OUN figures. There he lived in the premises of the Ukrainian Bureau of the OUN together with Ivan Habrusevych. The latter was in charge of ideological training of the referentura. So they talked mostly about political and ideological topics. But I. Habrusevych did not have the task of purposefully checking P. Sudoplatov. Soon, he (Sudoplatov) had a meeting with Riko Yaryi, Volodymyr Stakhiv, Mykhailo Seleshko, Orest Chemerynskyi, and other figures. The meeting was introductory and general in nature.

As noted in the report, on March 26, 1936, he had his first meeting with E. Konovalets in the presence of R. Yaryi and I. Habrusevych. The OUN leader first asked about his biography, the state of affairs in the Ukrainian ssr, the prospects for the struggle, and other general questions. A few days later, Ye. Konovalets invited P. Sudoplatov for a walking tour of Berlin, which lasted almost until midnight. During the walk, he was already looking more closely, discussing the forms and methods of work in the underground, the search for reputable people who could be involved in this work. At the same time, according to P. Sudoplatov, he did not feel any suspicion or alertness toward him. Obviously, the previous reviews of other members of the Provid of the OUN made a positive impression.

Ye. Konovalets mentioned that he would be glad if P. Sudoplatov and V. Khomyak could find and help smuggle to Europe a well-known Ukrainian with a name like Oleksandr Shumskyi, whom he would introduce to international circles to draw attention to the resolution of the Ukrainian issue. At this, he was interested in the fate of Shumskyi himself, what was happening to him and whether his escape abroad could be organized. (At that time, Ukrainian soviet and party leader Shumskyi was in exile in Krasnoyarsk for anti-soviet nationalist activities, killed in 1946 on stalin’s instructions and with the direct participation of P. Sudoplatov on his way from exile to Kyiv).

After the story about stay in Berlin, P. Sudoplatov described his trip to Vienna, where he arrived on April 11, 1936. He lived in the apartment of Roman Sushko, the chief representative of the OUN in Vienna. He characterized him as a great conspirator, a cautious and rather cunning man. In the evening, he would always curtain the windows, making sure that Bolshevik or Polish agents could not spy on what was happening inside the apartment. According to P. Sudoplatov, he asked questions that could lead to negative consequences if answered incorrectly. He attributed this to the fact that he continued to be checked. According to the report, he allegedly passed this check successfully. He pointed out that R. Sushko hugged him, kissed him and gave him his Browning pistol as a farewell gift.

In Vienna, P. Sudoplatov met a member of the OUN leadership, Yaroslav Baranovskyi. He characterized him as a nationalist fanatic and one of the most influential figures in the OUN, who was completely devoted to Yevhen Konovalets and, among other things, took care of his safety. The report emphasized that they had developed a good relationship with Ya. Baranovskyi and that the latter brought a large package of oranges to the station as a farewell.

Oleh Kandyba (codename “Olzhych”) was allegedly summoned from Prague specifically to meet P. Sudoplatov. They talked about cultural life in the Ukrainian ssr, Ukrainianization, literature, the possibility of smuggling banned works to the West and publishing them, sending literature and necessary publications to Ukraine. “Olzhych” impressed him with his radicalism in the struggle for Ukrainian national interests. Therefore, in the report, he pointed out that he “must be placed under constant surveillance in Prague”. He also added that O. Kandyba worried about his close relatives who remained in the Ukrainian ssr. “We must find them”, Sudoplatov suggested in the report, “and also keep an eye on them”.

On April 29, in the presence of I. Hrybivskyi and Ya. Baranovskyi, a meeting with Yevhen Konovalets took place in a Vienna coffee shop. The next day, the same group discussed how P. Sudoplatov envisioned the development of underground work after his return to the Ukrainian ssr, gave advice and made adjustments.

Information about the OUN underground network in the Ukrainian ssr, the growth of the circle of supporters, and the development of plans for the struggle for Ukraine’s independence was exactly what Yevhen Konovalets wanted to hear, what he desired and was trying to do himself. In this situation, P. Sudoplatov became the missing link. And he tried to fill this niche to the fullest and to please the OUN leader in every way possible.

P. Sudoplatov described in detail his meeting with E. Konovalets in the park near Schönbrunn Palace on May 16, 1936. He noted that they talked about establishing communication with the underground in the Ukrainian ssr, crossing points, tactics and methods of struggle. They also discussed individual terror. P. Sudoplatov, given the recommendations and instructions by the leadership of the nkvd, allegedly opposed the use of this method. He argued that it was quite difficult to do so in the territory of the Ukrainian ssr under the conditions of the time, especially regarding party leaders Postyshev, Kosior, and Balytskyi.

At this, he cited the following dialog:

“Konovalets: “Well, you are denying the need to use terrorist acts today, but if you had to deal with a person who was harming the Organization and it became necessary to kill him or her. Would you be able to execute such a decision?”

I: “That’s a completely different thing”.

At the same time, I began to tell a story I was making up as I went along, about how I had personally dealt with such a person a couple of years ago.

Konovalets interrupted my story and said that he did not need to know the details.

“So you have revolutionary experience”, he said.

“I do”, I replied”.

(FISU. – F. 1. – Case 31. – V. 8. – P. 132).

In this regard, interesting are the parallels with P. Sudoplatov’s memoirs from the book “Special Operations. lubyanka and the kremlin, 1930-1950”. In them, he mentioned that at an audience, stalin, speaking about further measures against Yevhen Konovalets, said that the goal was to deprive the Ukrainian movement of a leader and force its leaders to destroy each other in the struggle for power. “At parting, stalin asked me,” P. Sudoplatov wrote, “whether I correctly understood the political importance of the combat mission I was entrusted with. “I do”, I answered, and assured him that, come the need, I would give my life to fulfill the Party’s task”.

According to P. Sudoplatov, they soon returned to the discussion of the use of the method of individual terror in a conversation with Ye. Konovalets. They discussed the possibility of assassinating stalin. P. Sudoplatov himself provoked such a conversation to find out if there were any plans for that. Before that, Ye. Konovalets mentioned that a certain international group abroad was allegedly working on this issue. “But I have little faith in the success of this case,” he added, “It is unlikely that they will succeed, since stalin is very thoroughly guarded... In general, I must tell you that I, being ready to sacrifice my life to kill Kosior or Postyshev, would not raise a hand against stalin. stalin is Georgian. If he is killed, the muscovites will replace him with one of the insiders, a russian, and that will be even worse for Ukraine” (FISU. - F. 1. – Case 31. – Vol. 8. - P. 135).

Summarizing the conversation and trying to take additional credit for it, P. Sudoplatov wrote in his report that it was thanks to his persistent attempts to persuade Ye. Konovalets that individual terror methods were harmful to the cause that the latter allegedly agreed that they would not be used at least in the near future. What really happened during the conversation is unknown.

A separate part of the report is devoted to P. Sudoplatov’s stay in Paris. Here is how he described his meeting with Ye. Konovalets on June 7, 1936: “Having asked about how I was, he offered to walk with him around the city. We went on foot to the Champs Elysees, walked around almost all the major boulevards. He took me to the cemetery, showed me Petliura’s grave, and asked me to visit the grave again and lay flowers on his and my behalf. All that day, as well as the following days, with a short break, from morning till night, I was in the company of Konovalets and partly Boykiv. Together we walked from one place to another, from one coffee shop to another, he showed me some memorable places in Paris, and we went to the movies” (FISU – F. 1. – Case 31. - Vol. 8. - P. 145-146).

The report does not mention the handful of earth that P. Sudoplatov took from the grave and wrapped in a handkerchief, his emotions about it, and other emotions that he later described in his book. This is despite the fact that P. Sudoplatov reported the smallest details about each meeting. Therefore, the story with the earth could also have been invented to achieve the desired effect and for the sake of self-aggrandizement in front of the nkvd leadership.

Among the documents of the operational case “Residentura “Stavka”, there were also found reports from other nkvd agents, which show that members of the OUN Provid did not trust P. Sudoplatov as much as he convincingly described in his report. In particular, Mykhailo Seleshko, a member of the OUN department in Berlin and then Ye. Konovalets’ secretary, said in a confidential conversation that the OUN Provid did not believe P. Sudoplatov (in the report, the agent calls him by one of his pseudonyms abroad – Pavlo, Pavlus) “and quite possibly it was Pavlo, through whom the Organization came into contact with the gpu”.

When asked by the agent why the Organization cares about him so much and is so attentive to him, M. Seleshko replied: “We are 99 percent sure that Pavlo is a chekist, but one percent remains in his favor. We have great faith in the people who sent Pavlo here... Besides, Konovalets decided to be “attentive” to Pavlo to the end, just in case, so as not to give him any reason to take revenge on our people “there” if he is indeed a chekist. So Pavlo will not know what we think of him. On the contrary, we are doing everything in such a way that he has no doubt that we trust him completely.”

This is stated in agent “Pavlo” (Kindrat Poluvedko)’s message, dated July 1936. At the end of the message, it is noted that at a farewell dinner in Berlin shortly before P. Sudoplatov’s return to the ussr, M. Seleshko hinted that despite this reception, he was still not trusted in the Organization. And later, in private, he explained to the agent “that he did it in order to make it clear to “this bad guy” that his role was clear to the Organization, that it would hurt him, Seleshko, if “this bad guy” left with a clear conscience of an honest man” (FISU. – F. 1.– Case 31. - Vol. 7. - P. 194-195).

P. Sudoplatov's description of his meeting with E. Konovalets and Ya. Baranovskyi in Berlin after his trip to Paris is also important for understanding the course of all subsequent events. “We walked and talked for several hours,” the report says, “Baranovskyi translated from German into Ukrainian a message from Geneva about the arrest of Norman and others who had been conducting surveillance of Konovalets’s apartment. Konovalets told me that the arrested had found a plan of his house and that the bolsheviks apparently wanted to kill him... I expressed my sympathy to Konovalets for having to go through so much, asked him to take care of himself, to cover his tracks in Europe. The three of us discussed the possibility of Konovalets’s going completely underground. “No final decision was made... I said that it was difficult for me to speak on this issue because I did not feel competent enough. One thing, I said, is clear to me, – that Colonel should be completely safe and preserved for the Ukrainian revolution” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 31. – Vol. 8. –P. 155-156).

The Norman in question is the soviet intelligence officer Ivan Kaminskyi, who was sent to Switzerland by the leadership of the nkvd at that time with a passport of a Danish citizen Karl Nordman. The task was actually to monitor Konovalets and collect information about his plans and intentions. But not to kill him.

After P. Sudoplatov returned to the ussr in September 1936, as testified by the case file, his report on the trip was carefully analyzed by the nkvd. One of the main questions that they wanted to finally clarify was whether or not the members of the OUN Provid believed him. V. Khomyak-“Lebed” was also involved in that. He drew attention to O. Senyk’s suspicions, the actions of members of the Berlin OUN group I. Habrusevych, R. Yaryi and others, which he interpreted as provocative, R. Sushko’s insistent attempts to give P. Sudoplatov a photograph of Ye. Konovalets as a souvenir, the initiation of talk of individual terror, and other issues. Eventually, they concluded that “a number of moments characterized the Provid’s suspicious attitude to him”.

Nevertheless, the line of behavior was adjusted and it was decided to continue the operation “Stavka”. To dispel suspicions, P. Sudoplatov sent a letter to members of the OUN Provid. In it, he flatteringly tried to persuade all of them of his commitment to the Ukrainian cause. “I would like to write a lot,” he pointed out, “about how proud I am of my involvement in the movement and being one of the small organizers, about how proud I am of belonging to the Ukrainian nation... Realizing the absoluteness, inevitability, and necessity of armed struggle, we persistently forge our forces in the deep underground, believe in our truth, the Ukrainian nationalist truth. And from there, from the underground, we shout to you, our brothers, we shout: “Glory to Ukraine!” We carry this slogan in our hearts, with it we will organize the people, our brothers died with this slogan on their lips, with it we will win” (FISU – F. 1. – Case 31.– Vol. 8. – P. 238-239).

What happened next is known from open sources, eyewitness accounts, and the materials of the investigation by the Police of the Netherlands. At the same time, it is currently impossible to trace the further course of events based on the materials of the nkvd, which are stored in the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine’s archive, since the file does not contain documents related to the operation from the end of 1936 to May 1938. Those plans, instructions and briefings that reflected P. Sudoplatov’s next several trips abroad, the choice of the method and instrument of murder, the mechanism of using explosives, the escape route and other issues were developed and approved in moscow. Therefore, they are still stored there in classified archives.

The documents found in the archive of the FISU, although they do not cover all stages of the operation, still allow us to come closer to understanding what happened on May 23, 1938 in Rotterdam, to clarify the role of all parties, to understand why the stalinist regime managed to carry out this high-profile political murder, and why its perpetrator so boldly gained the trust of the members of the OUN Provid and the Providnyk (leader- Transl.) himself.