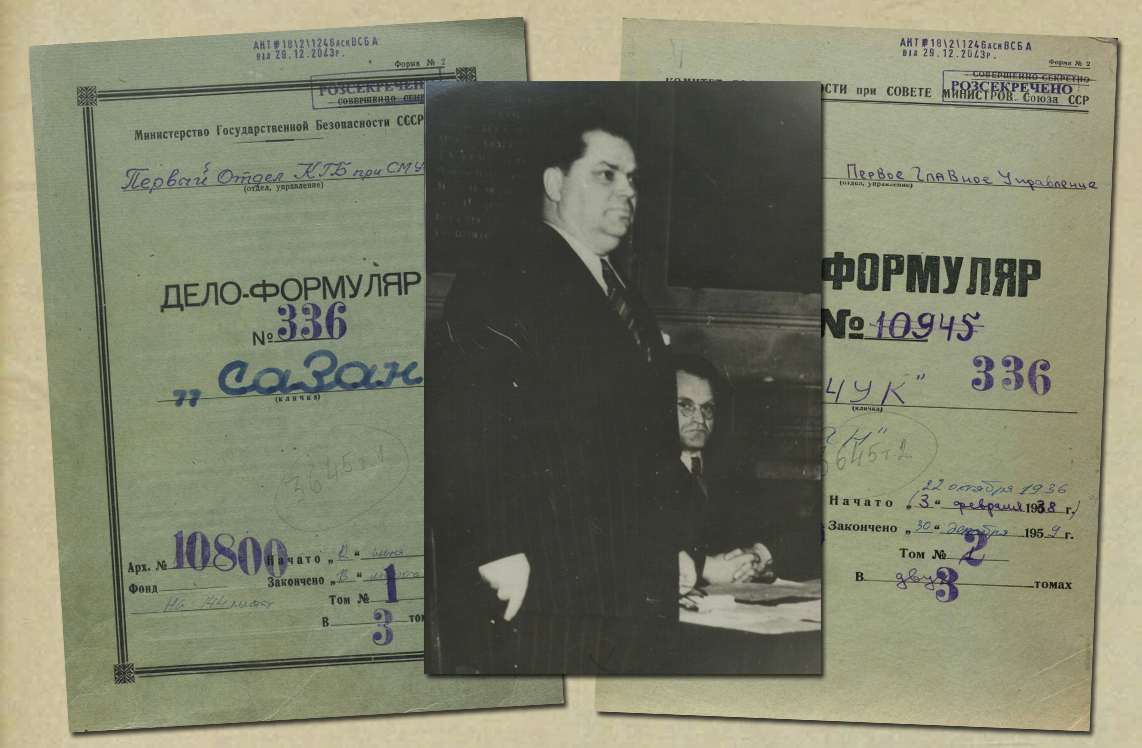

Symon Sozontiv. The Guardian of Ukrainians in France and the kgb’s “Guardianship” over Him

1/15/2026

The kgb’s operational case against Symon Sozontiv was code-named “Kauchuk” (“Rubber” – Transl.) This was because he owned a small rubber goods factory in France. But he was of interest to the chekists not only as a businessman and patron of the arts, but above all as the long-time head of the “Ukrainska Hromadska Opika” (“Ukrainian Community Care” – Transl.) in France and later as the head of the executive body of the Ukrainian National Council (Prime Minister of the Government in exile). They intended to use his certain character traits, political vacillations, and ambitions to carry out a special propaganda operation.

From A Senior Officer of the Army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic – to a Factory Director in France

In the 1950s, the ussr kgb residentura in Paris obtained some technological secrets of rubber production for aircraft tyres through its agents. That was considered a significant achievement for soviet intelligence. So, when one of the residentura’s employees involved in the case noticed the director of a rubber products factory, they wanted to pursue the matter further. But they quickly realized that the products were unlikely to be of any interest. The factory was small. Since the 1920s, it had been manufacturing rubber soles for shoes, bicycle parts, and other products for civilian use. Among other local enterprises, the factory stood out because all of its employees were Ukrainians, as was the owner. It was Symon Vasyliovych Sozontiv who drew the attention of the kgb agents. He was of greater interest to them than any scientific or technical secrets.

According to declassified documents from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine, the operational cultivation of S. Sozontiv was intensified in the mid-1950s, while the case file on him had been kept since 1936. During that period, a lot of materials were accumulated in the case, which described his life in detail. That biographical information is not even available in open sources today.

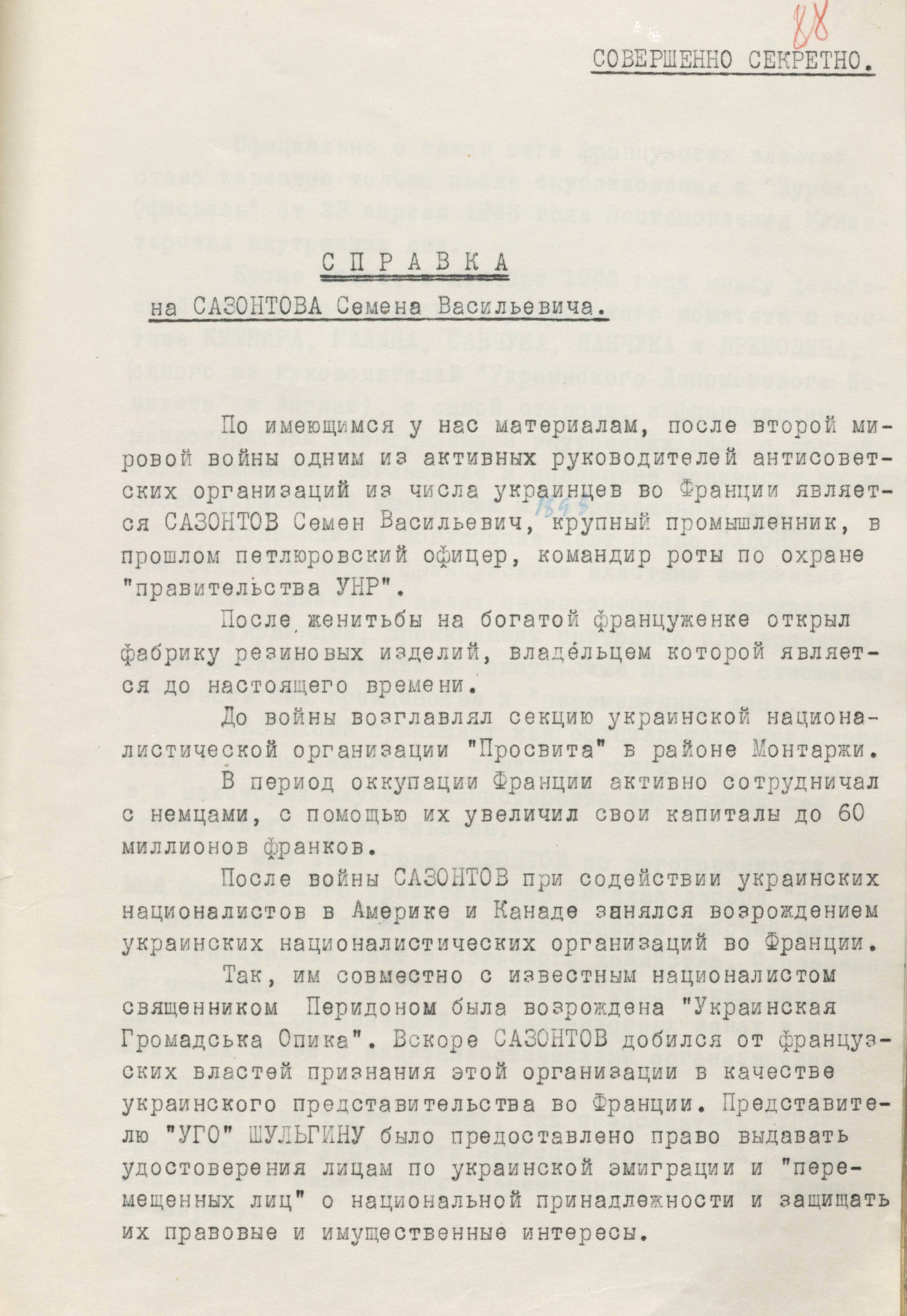

According to agents’ reports, testimonies of close relatives, and other materials obtained by the chekists, Symon Sozontiv was born into a clergyman’s family in 1898 in the village of Murafa in now Bohodukhiv district of Kharkiv region. There were three sons and five daughters in the family. Symon graduated from a technical school and in 1916 entered the Kharkiv Technological Institute. But soon he was mobilized into the army and graduated from the ensign school. During the period of the Ukrainian Central Rada, he participated in the Ukrainization of military units of the russian imperial army. In the Army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, he allegedly commanded a company that was involved in guarding the Government, held certain positions in the Zaporizhzhia Corps, and was a course senior officer in a youth school.

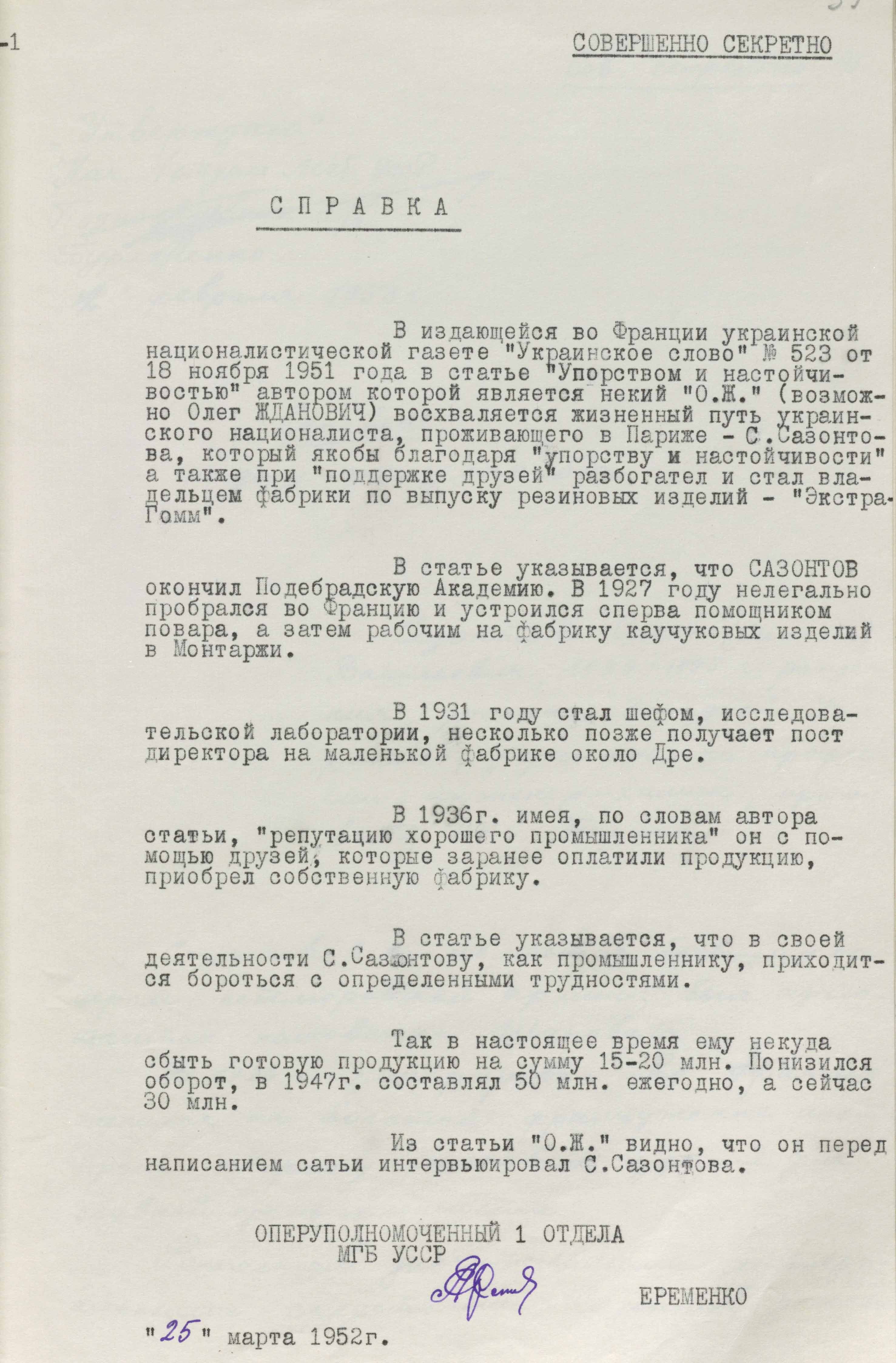

After the defeat of the liberation struggle, he ended up in Poland in camps for interned persons. In 1923, he moved to Czechoslovakia. There, in 1927, he graduated from the Ukrainian Economic Academy in Poděbrady with a degree in engineering and technology. After that, he moved to France. At first, he worked as an assistant cook, then as a laboratory assistant and head of a research laboratory. In 1937, he left for Paris. He got a job at a factory manufacturing rubber products, and soon, with the help of friends and after a successful marriage, he accumulated some capital and became the owner of a small factory.

The factory employed about 40 workers, mostly from Halychyna. There were periods of growth and decline in production. Sometimes the turnover of capital ranged from 30 to 50 million francs per year. To achieve this, everyone had to work hard. One of the agents, at the request of the nkvd residentura in Paris, described S. Sozontiv’s situation at that time and his character traits as follows: “He has a broad, lordly, and lordly despotic nature.... Earlier, when he had money, he received almost all guests, entertained them, and fed them. But then, he did not refuse even ordinary people. Many ordinary people lived in his houses, and they did not pay a penny. At the factory, he exploited workers, but he also helped people, found them jobs, and brought them from the provinces to Paris...” (FISU – F. 1. – Case 10800. – Vol. 1. – P. 140).

Other documents mention that S. Sozontiv used his own money to maintain homes where orphans of deceased Ukrainian soldiers were raised and elderly people were housed. He made substantial contributions to the Ukrainian People’s Union in France, donated to Ukrainian émigré organizations, and financed newspapers. At the same time, his activities were not limited to material support.

“Ukrainian” Should Be Written in the Passport”

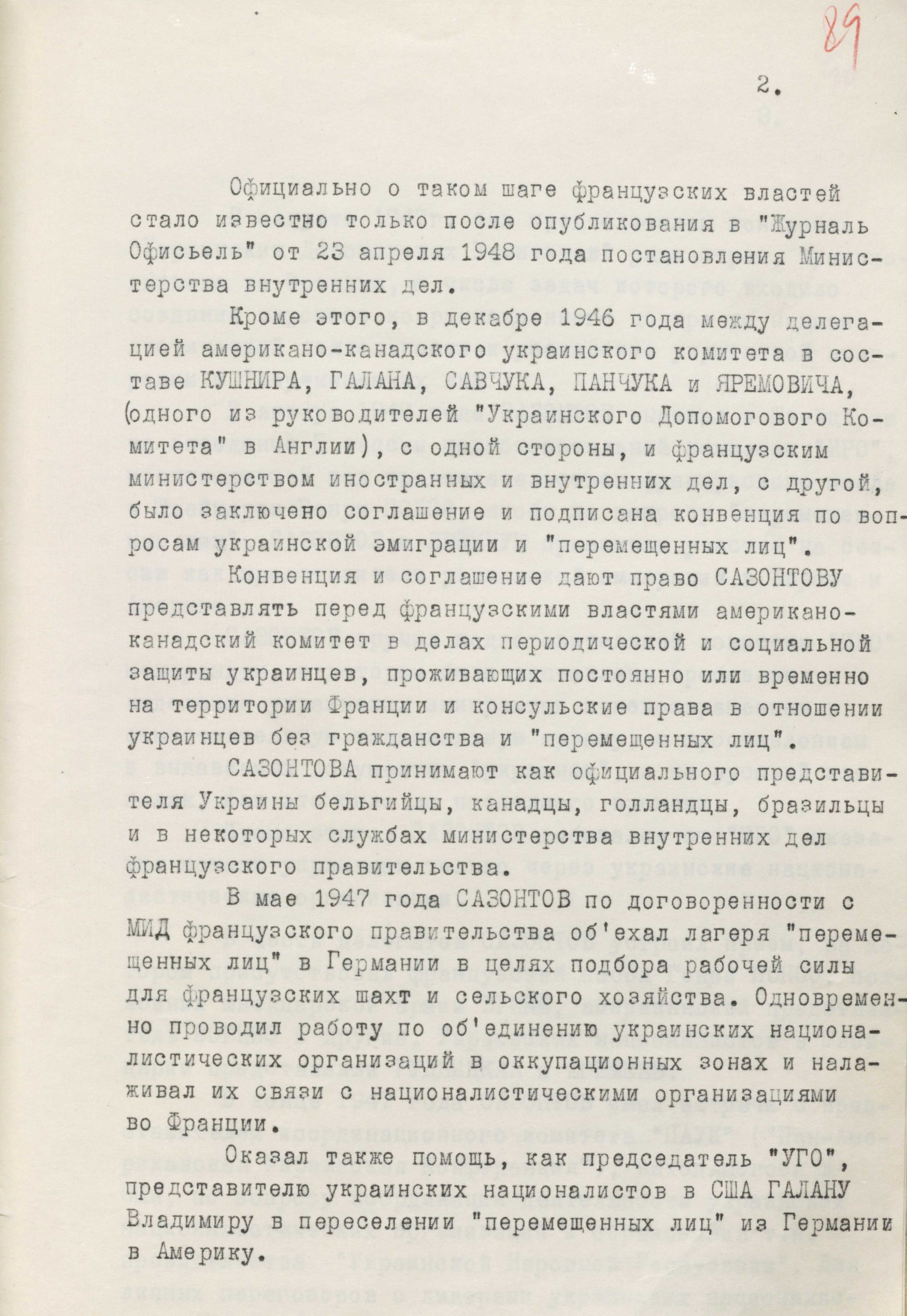

“At the end of 1946, Sozontiv created a charitable organization “Ukrainska Hromadska Opika” (“Ukrainian Public Care”– Transl.) – reads one of the kgb documents – “which, with the assistance of the American-Canadian Ukrainian Committee, was soon recognized by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior as a Ukrainian ‘office’ with consular functions, and Sozontiv then began to act as ‘Ukrainian consul’ before foreigners,” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10800. – Vol. 2. – P. 84).

The paper also says that the relevant agreement and convention were signed, recognizing “Ukrainska Hromadska Opika” as the Ukrainian representative office in France. At the same time, Oleksandr Shulhyn, a representative of the “Ukrainska Hromadska Opika”, who had long served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Ukrainian People’s Republic Government in exile, was granted the right to issue IDs to Ukrainians confirming their nationality and to protect their rights.

At this, it points out that at a meeting of one of the sessions of the International Organization for Refugees of the League of Nations, S. Sozontiv insisted that Ukrainian emigrants be separated into a separate independent national group and that “Ukrainian” be written in the nationality column when issuing documents to them. For Ukrainian activists, this issue was very important and fundamental. After all, back in the 1920s, France and other European countries believed that the Ukrainian people did not exist and that Ukrainians were an ethnographic part of the russians, and had no right to claim their own statehood, identification, and language. This was facilitated by the fact that in France, the huge russian diaspora perceived Ukrainians from eastern regions of Ukraine as ordinary russians. Those people were persistently absorbed into the russian cultural environment. Instead, a hostile attitude was cultivated to Galicians, Bukovinians, and, in particular, supporters of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, whom the russians called Petliurists and created other negative names for them. This also affected the official government circles’ attitude to Ukrainians.

Therefore, when in 1922, on the initiative of the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Norwegian researcher F. Nansen, international documents for stateless persons and refugees (so-called Nansen passports) were introduced, Ukrainian emigrants received them marked “russian”. Representatives of the Ukrainian People’s Republic Government in exile insisted that this was wrong and unacceptable in relation to Ukrainians. O. Shulhyn and V. Prokopovych were the most active in this regard. Newly declassified documents show that S. Sozontiv was also directly involved in this work.

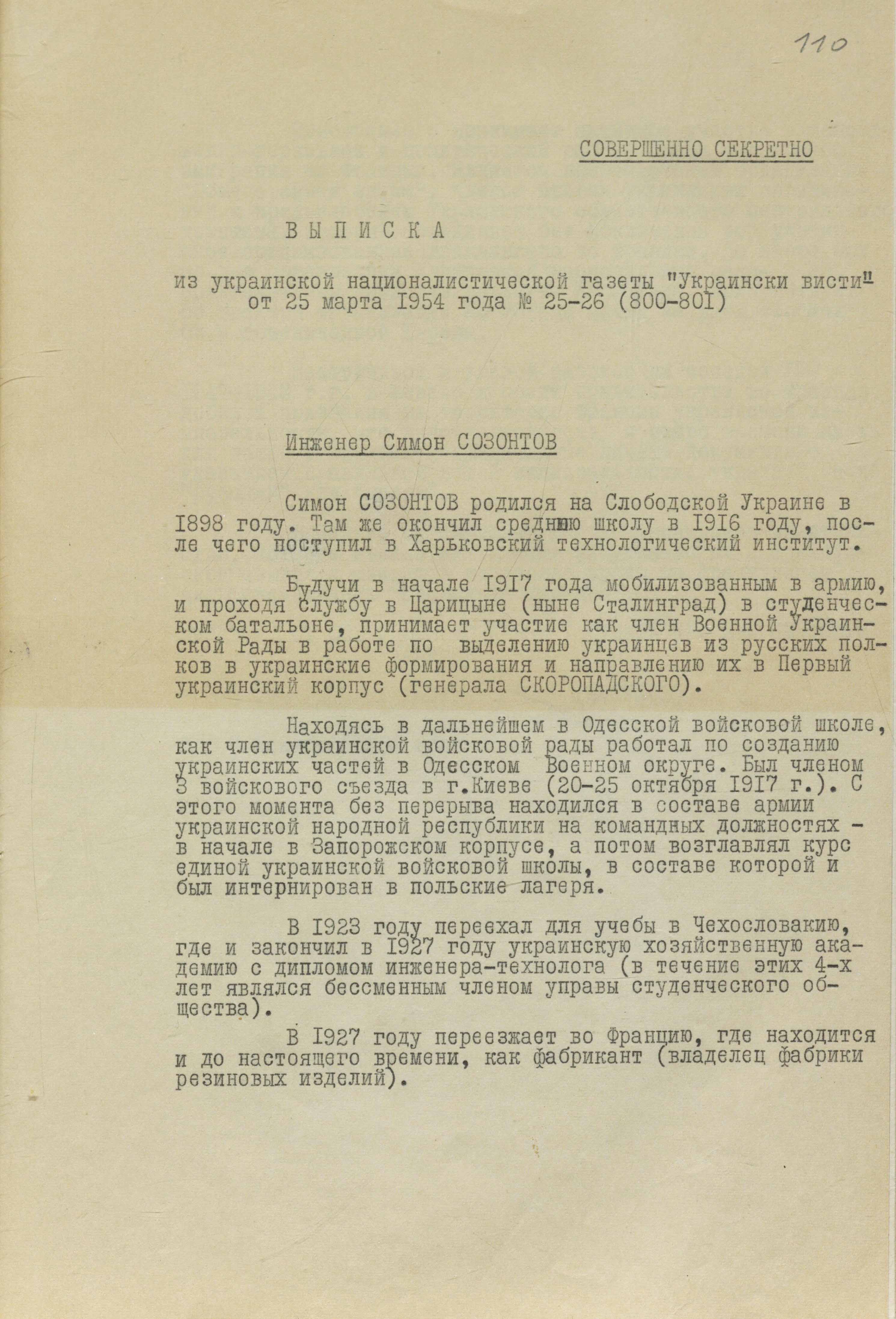

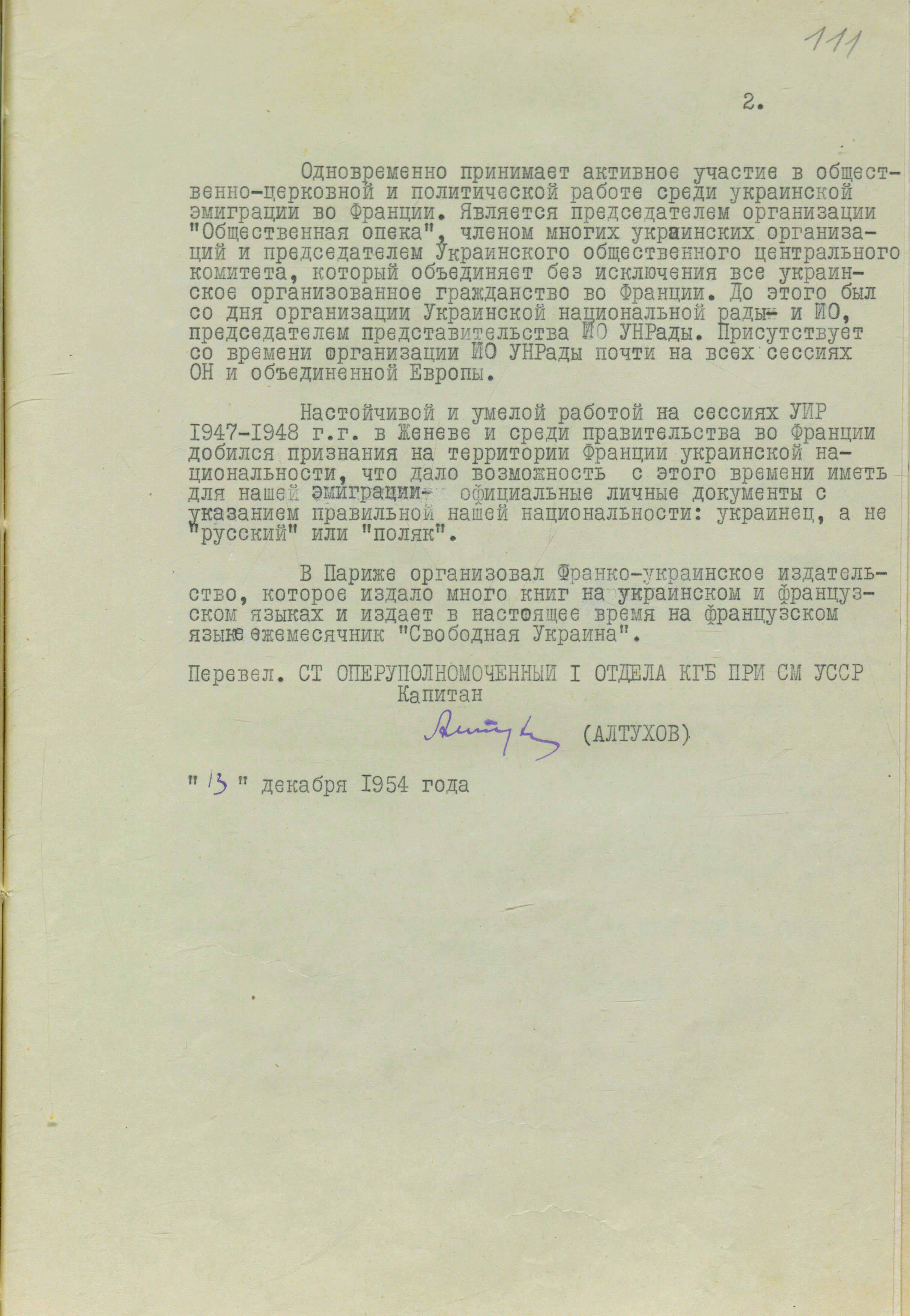

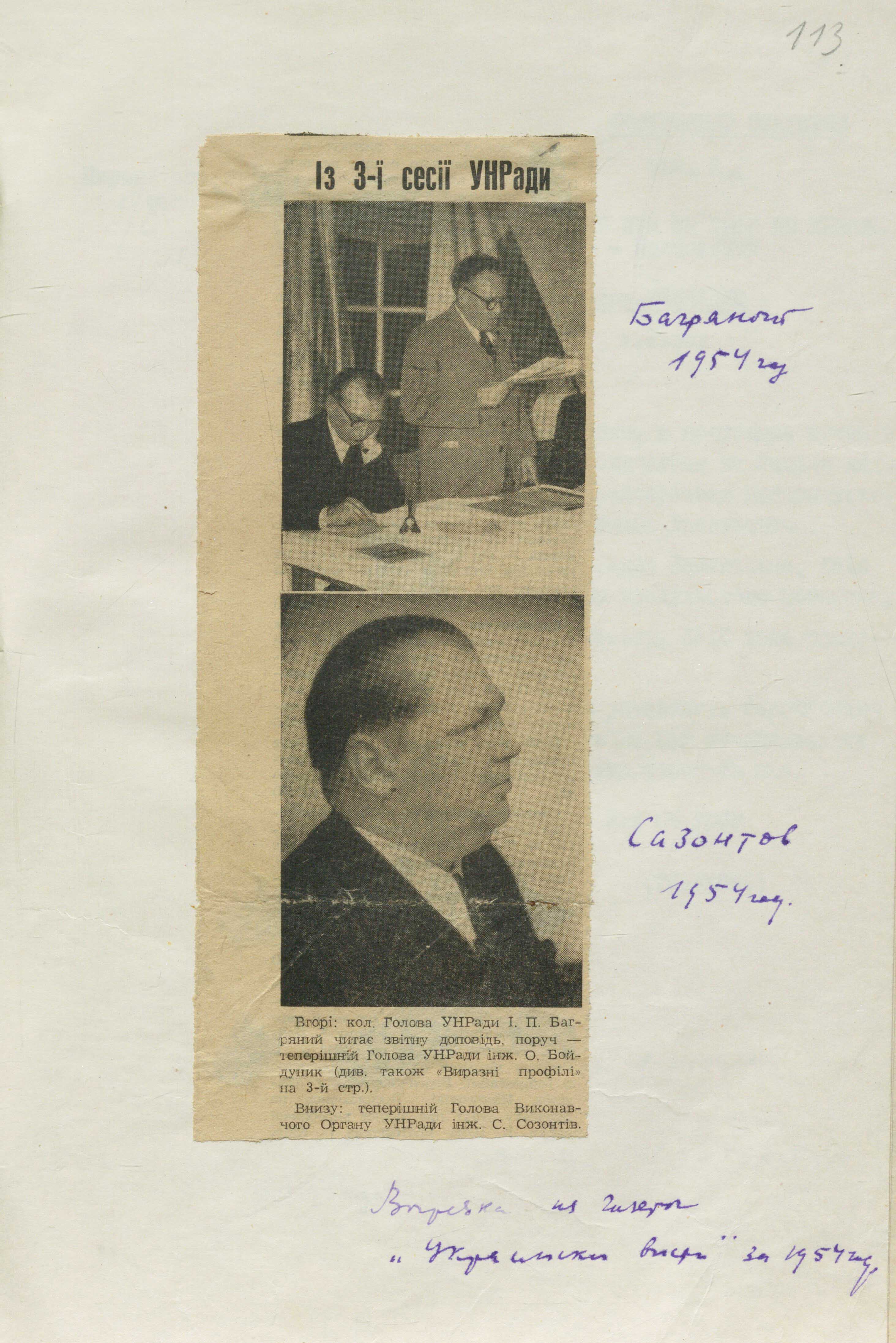

This is confirmed by a quote from the emigrant newspaper “Ukrainski Visti” dated March 25, 1954, which is attached to the case file. It mentions that S. Sozontiv, through his “persistent and skillful work at the 1947-1948 sessions in Geneva and among the French government, achieved recognition of Ukrainian nationality on French territory, which made it possible for our emigrants to have official personal documents with the correct indication of our nationality: “Ukrainian” and not ‘russian’ or “Pole” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10800. – Vol. 1. – P.110–111).

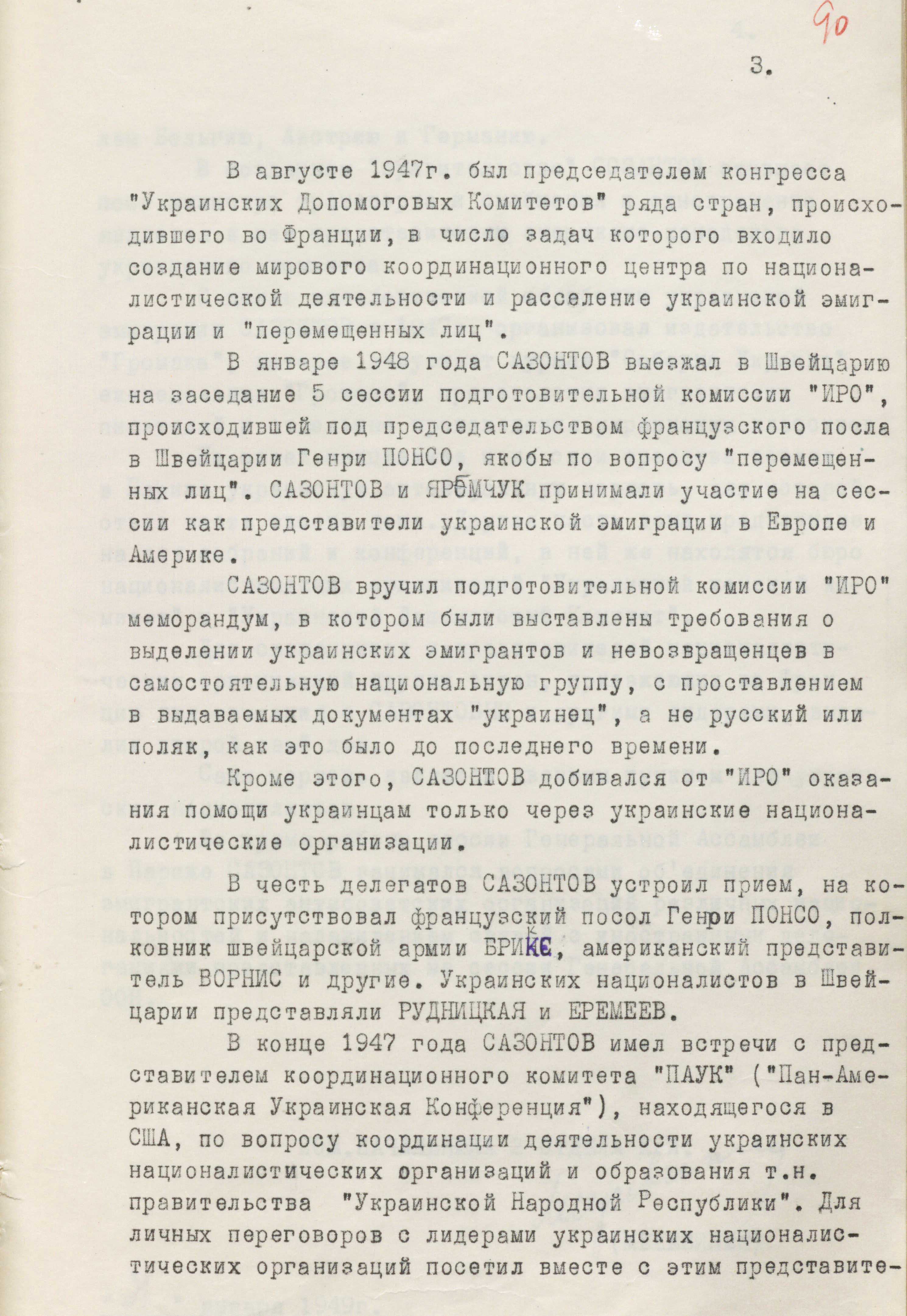

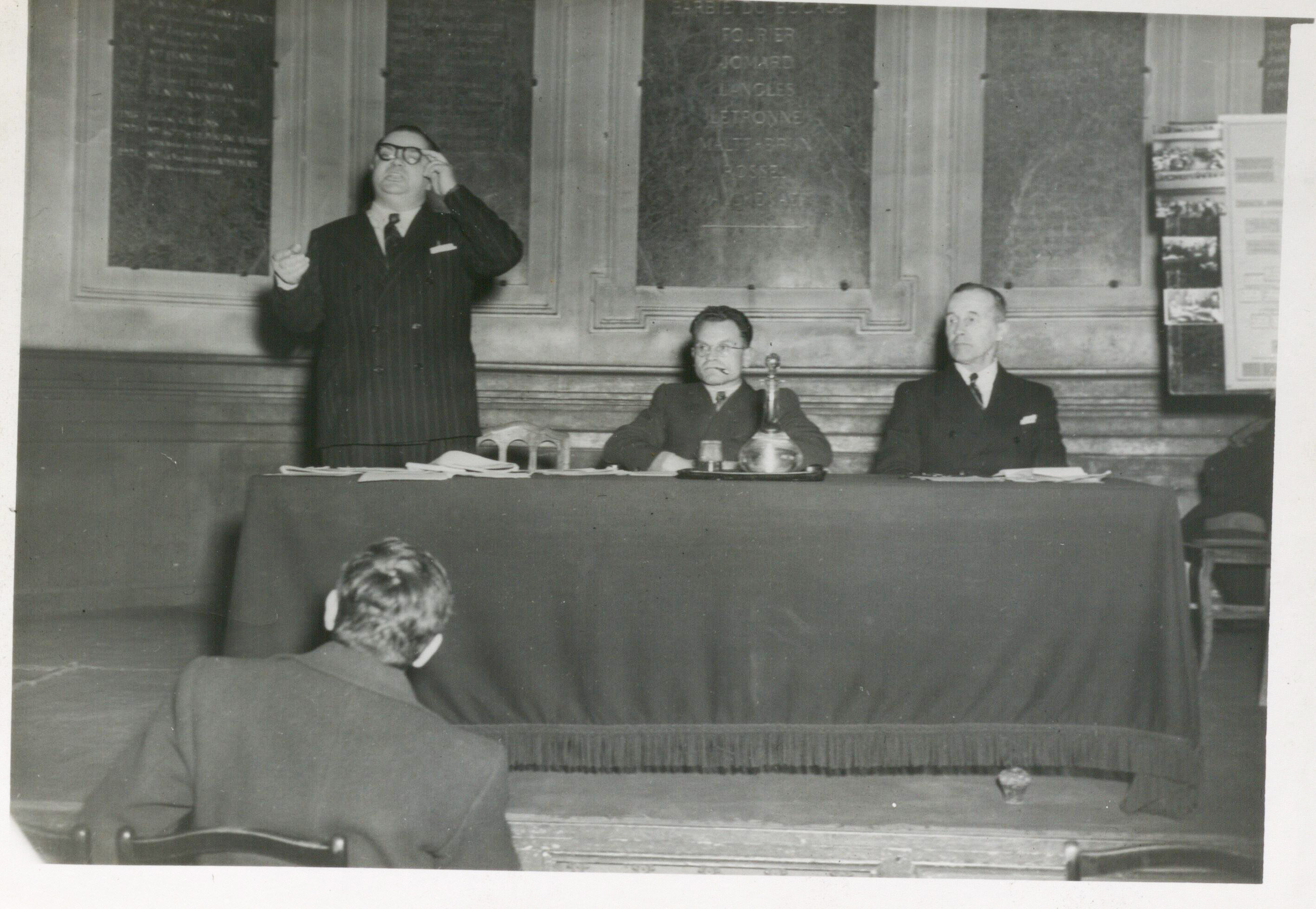

In 1940–1950, the kgb recorded S. Sozontiv’s significant activity on the international stage. They emphasized that he visited camps for displaced persons in Germany, helped Ukrainians move from there to the USA and other countries, chaired the Congress of “Ukrainski dopomohovi komitety” (“Ukrainian Aid Committees” – Transl.) held in France, and traveled to Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, and other countries to establish contacts with Ukrainian organizations.

Besides, the kgb pointed out that he showed great interest in the affairs of the Ukrainian church, in particular the activities of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church. Foreign agents reported on S. Sozontiv’s trip in the summer of 1947 to Wiesbaden, Germany, where he discussed the possibility of Metropolitan Mstyslav’s (Stepan Skrypnyk) moving to Paris to head the UAOC there instead of the deceased Archpriest Brynzan.

According to the case files, Mstyslav had an invitation to move to Canada at that time. However, he could not say No to S. Sozontiv. So, he stayed in France for several months, building up the Ukrainian church as the bishop of the Paris UAOC. In 1950, S. Sozontiv suggested that Metropolitan Polikarp (Petro Sikorskyi) move to France and, at the same time, transfer the Synod of the UAOC and the general church administration there. In return, he undertook to “build or purchase a house in Paris, where Polikarp would live and the UAOC administration would be located.”

One of the kgb reports noted the following about that activity:

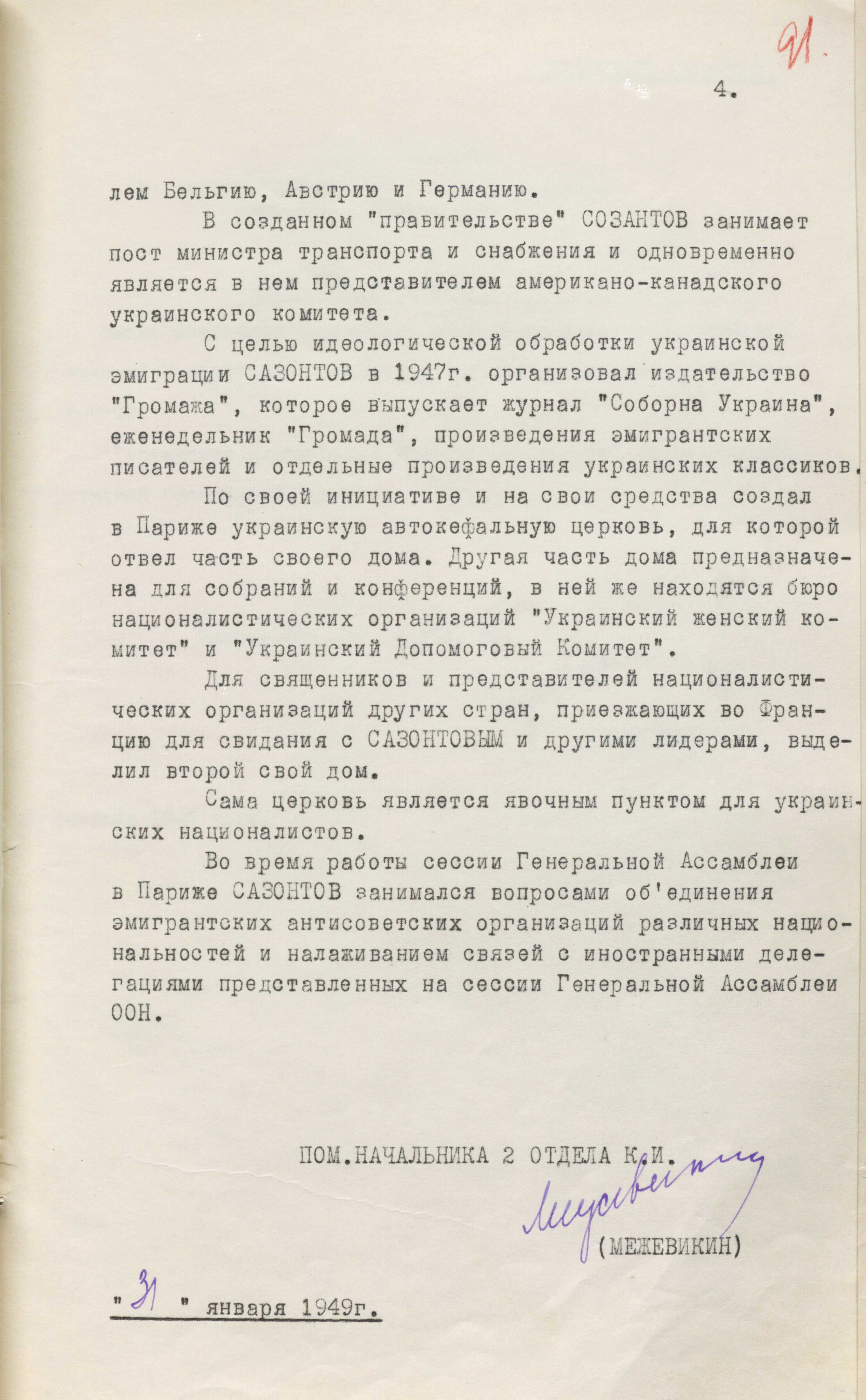

“On his own initiative and at his own expense, he established a Ukrainian autocephalous church in Paris, for which he allocated part of his house. The other part of the house is intended for meetings and conferences, and also houses the offices of nationalist organizations, the “Ukrainian Women’s Committee” and the “Ukrainian Aid Committee.”. He allocated his second house for priests and representatives of nationalist organizations who came to France to meet with Sozontiv and other figures. The church itself is a meeting point for Ukrainian nationalists” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10800. – Vol. 2. – P. 91).

Later, as shown by archival documents, when things at the factory were not going well, problems arose with financing the church premises and paying past bills and obligations. And it was then that unknown persons knocked on the door of S. Sozontiv’s apartment...

“For a Flat in Kharkiv and a Director’s Position”

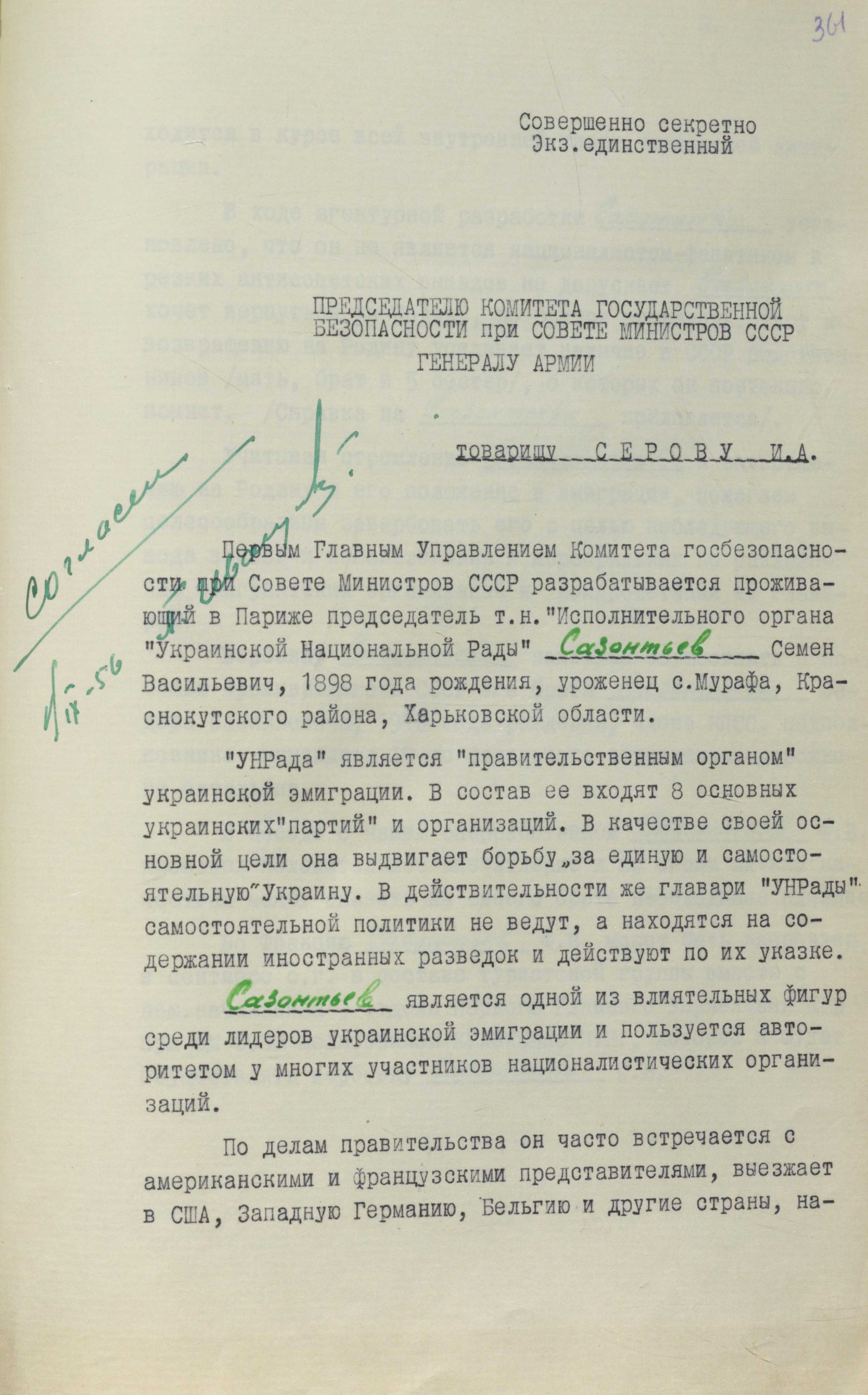

In May 1954, a document arrived in Kyiv from the central apparatus of the kgb of the ussr, stating that as a result of a series of reorganizations in the emigration Government of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, the position of head of the executive body was taken by “a vicious enemy of the soviet state, an agent of American and French intelligences” S. Sozontiv. In parallel, instructions were given to develop active measures against him. At the first stage, as was often the case in such situations, it was decided to “send greetings” from close relatives.

In the summer of 1956, a kgb agent under the cover of an official of the ministry of culture of the ussr was included in the delegation of actors from the Stanislavsky and Nemyrovych-Danchenko moscow Theater, which was going on tour to Paris. He was supposed to come to S. Sozontiv’s apartment and give his wife Yevgenia greetings and gifts from her brother in Kharkiv. That was just an excuse to meet the owner of the apartment. After general conversations about Kharkiv and life in soviet Ukraine, the guest invited the couple to the theater to see “Swan Lake”. Then there were walks through the city in the evening, dinner at a restaurant, requests to help with shopping, and casual conversations on various topics.

In his trip report, the operations officer wrote that S. Sozontiv held nationalist views, advocated for an independent Ukraine, interpreted the policies of the communist party of the ussr from the anti-soviet point of view and spoke harshly against stalin, collectivization, and russification. At the same time, he pointed out that the emigrant misses his homeland, asks to bring Ukrainian soil next time, and is afraid to return because he believes he could face a “high-profile trial”.

The conclusions noted that the first communication with S. Sozontiv showed that he was not a fanatical nationalist, agreed with some arguments in the discussions, approved of certain achievements in the Ukrainian ssr, and that his love for Ukraine, the presence of relatives in his homeland, and his expressed desire to “live out his life at home” could serve as grounds for recruitment.

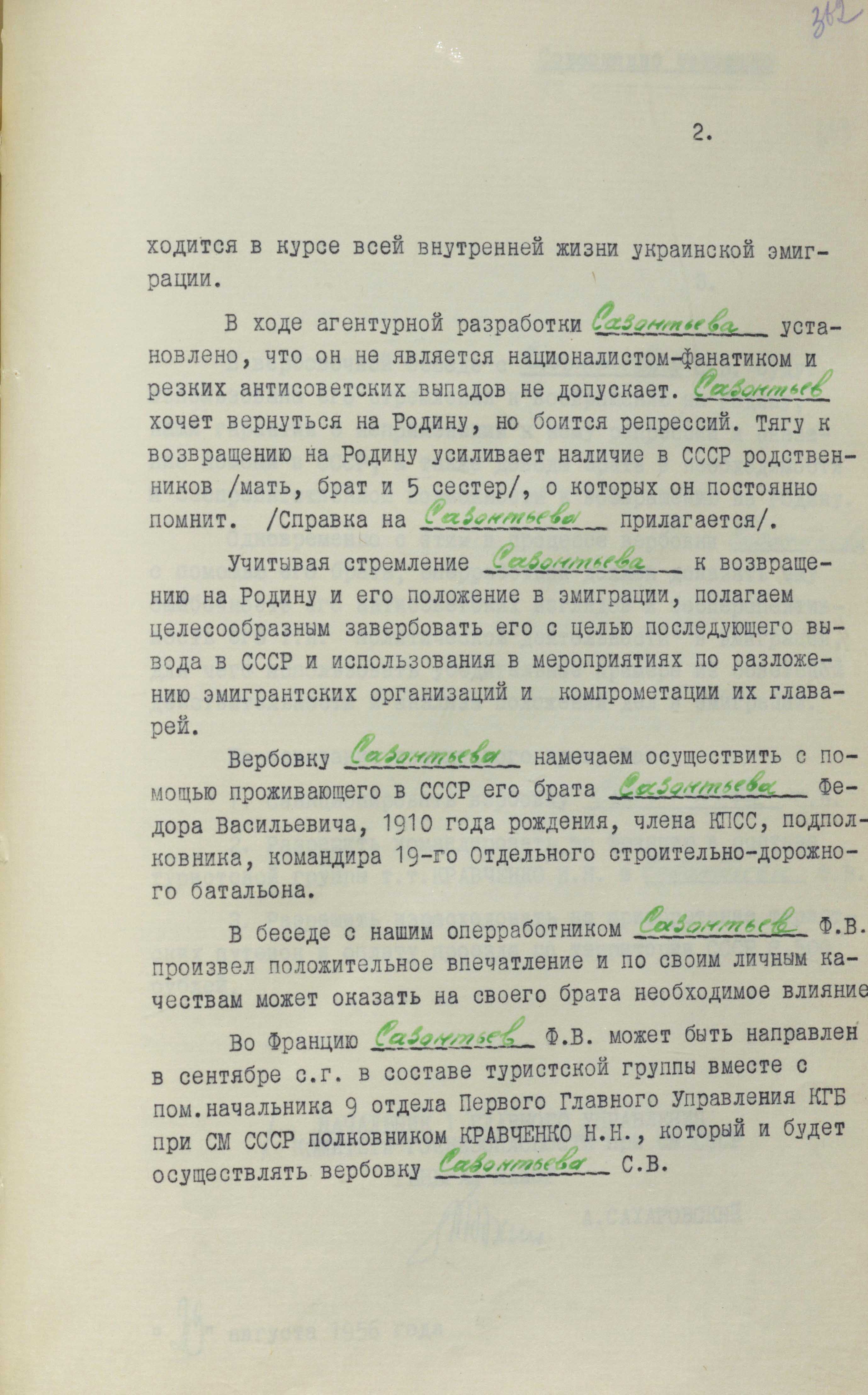

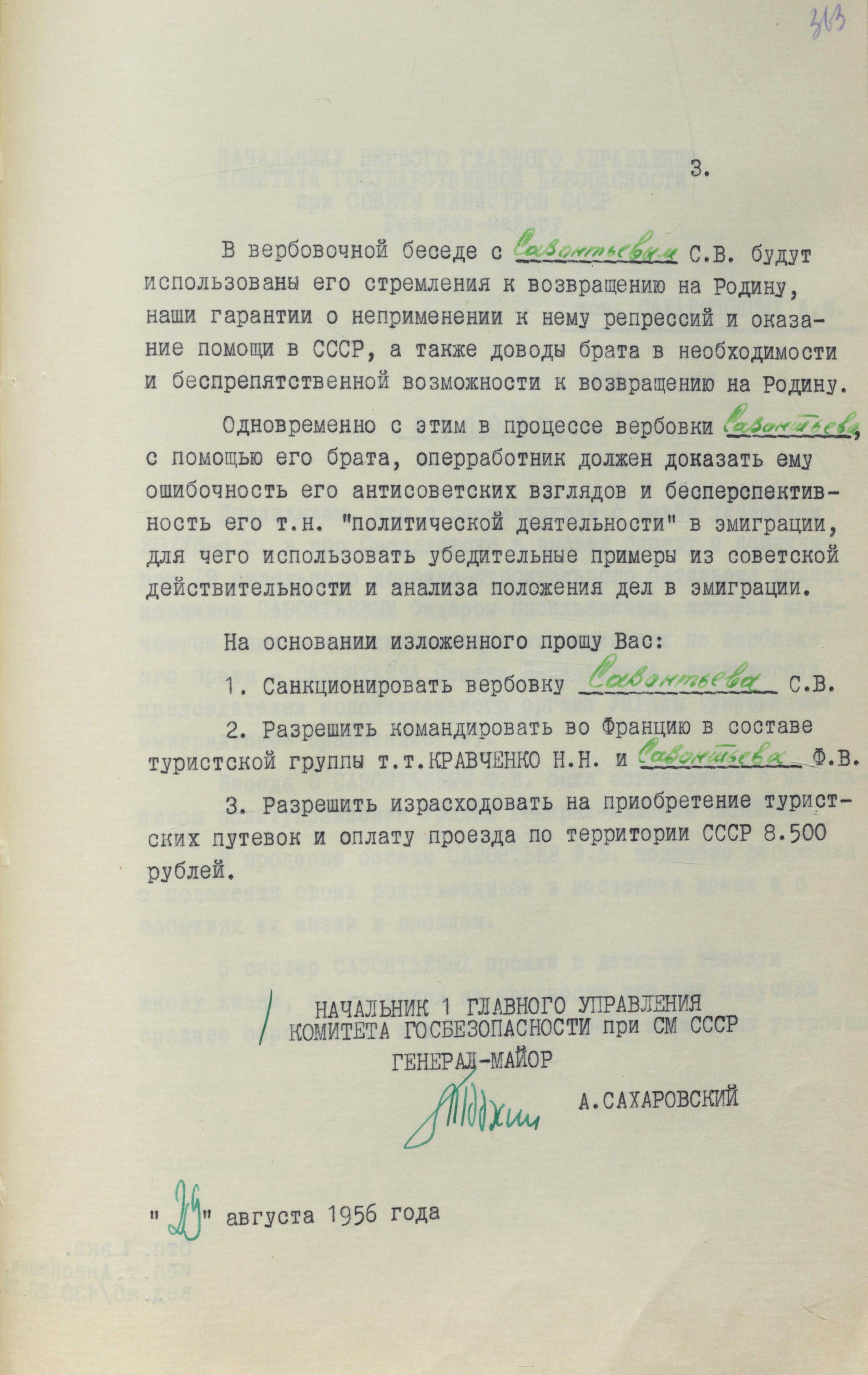

Following these conclusions, a report was prepared and signed by the head of the first main directorate (foreign intelligence) of the kgb of the ussr O. Sakharovsky, addressed to the chief of the kgb of the ussr I. Serov. It stated:

“Given Sozontiv’s desire to return to his homeland and his situation in exile, we consider it expedient to recruit him for the purpose of bringing him to the ussr and using him in measures to undermine émigré organizations and compromise their leaders.

The recruitment of Sozontiv is planned to be carried out through his brother, Sozontiv Fedir Vasyliovych, a citizen of the ussr, born in 1910, a member of the communist party of the soviet union, a lieutenant colonel, and commander of the 19th separate construction and road battalion.” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 10800. – Vol. 2. – P. 361–363).

kgb officers met with Fedir, the commander of the construction battalion, in Irkutsk, where he was serving. At first, he was wary of the visitors. He assured them that he did not correspond with his brother and knew nothing about his life. Then he confessed that he had previously been summoned for a conversation with the head of the army’s political administration on this matter. The latter informed him that his brother was living abroad and was an American spy. Since then, Fedir had been afraid of negative consequences for himself. At the same time, during the conversation, he began to condemn his brother and stated that “if I met him, I would first of all punch him in the face”.

Taking into account this position, which appealed to the chekists, Fedir was informed that the kgb wanted to use his help as an honest and devoted communist to persuade Symon to renounce his anti-soviet activities and return to his homeland. He willingly agreed to this.

So, according to the case files, in the autumn of 1956, Fedir was included in a tourist group that was being formed for a trip to France. Upon the tourists’ arrival, he was immediately met by employees of the Paris residentura, who told him over dinner what he should say to his brother the next day. They drove him to Symon’s flat, stopped at a distance, and showed him which entrance to use. They advised Fedir to take the gifts he had brought with him: two boxes of chocolates, a bottle of vodka, and a jar of pickled siberian mushrooms.

As Fedir mentioned in his report after the trip, they did not recognize each other, so much had both of them changed. Nevertheless, the conversation was warm. They mostly talked about close relatives and life in the ussr and France. The next day, they met in the park. As planned, Fedir came with an embassy employee. He introduced him as such. He also pointed out that the man was accompanying their tourist group and had volunteered to be his guide, since Fedir did not know French.

“I personally persuaded my brother Symon”, he wrote in his report, “that he should stop wandering, that he should decide and think about returning to his homeland – to Ukraine, which he praises and loves so much. At the same time, I told him that our homeland and Ukraine are suffering considerable damage from enemies, and that he, that is, Senya, must help our representatives – the embassy of the soviet union – in this matter, and in doing so he will atone for his guilt, if he feels he has any” (FISU. — F. 1. — Case 10800. – Vol. 2. – P. 397).

In turn, the “representative of the embassy” assured him that if S. Sozontiv agreed to return to the ussr, he would be provided with a good flat in Kharkiv and even some kind of managerial position at an enterprise in his field, since he was an experienced and respected person. But if he was not yet ready to make such a decision immediately, he could wait a little while and during that time prove that he really wanted to break with his current activities in exile and reconsider his views.

The conversation, which gradually took this turn, really made S. Sozontiv reconsider his views on the recent visits of guests to his home and be more cautious. This caution, even wariness, manifested itself during the next late evening visit to his place.

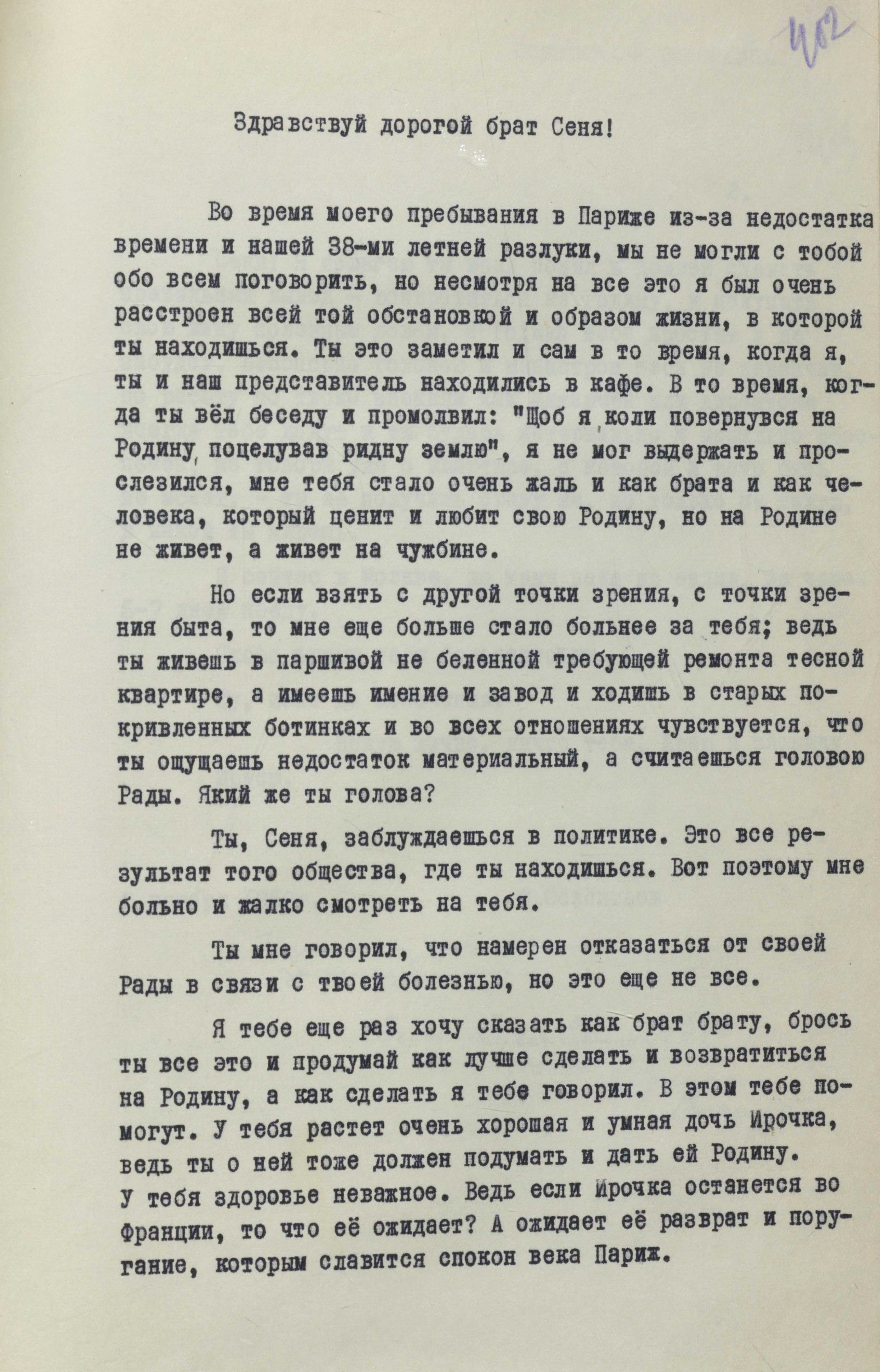

The visitor, who was already a familiar “representative of the embassy” and who was referred to as “Panas” in correspondence between the residentura and the kgb central office in moscow, described the meeting in detail in his report. He pointed out that S. Sozontiv initially did not even let him into the flat and from the very threshold asked what he wanted from him. “Panas” said that he had brought a letter from his brother. A copy of that letter, written under the dictation of the kgb agents, was attached to the case file. In addition to everyday matters, it read as follows:

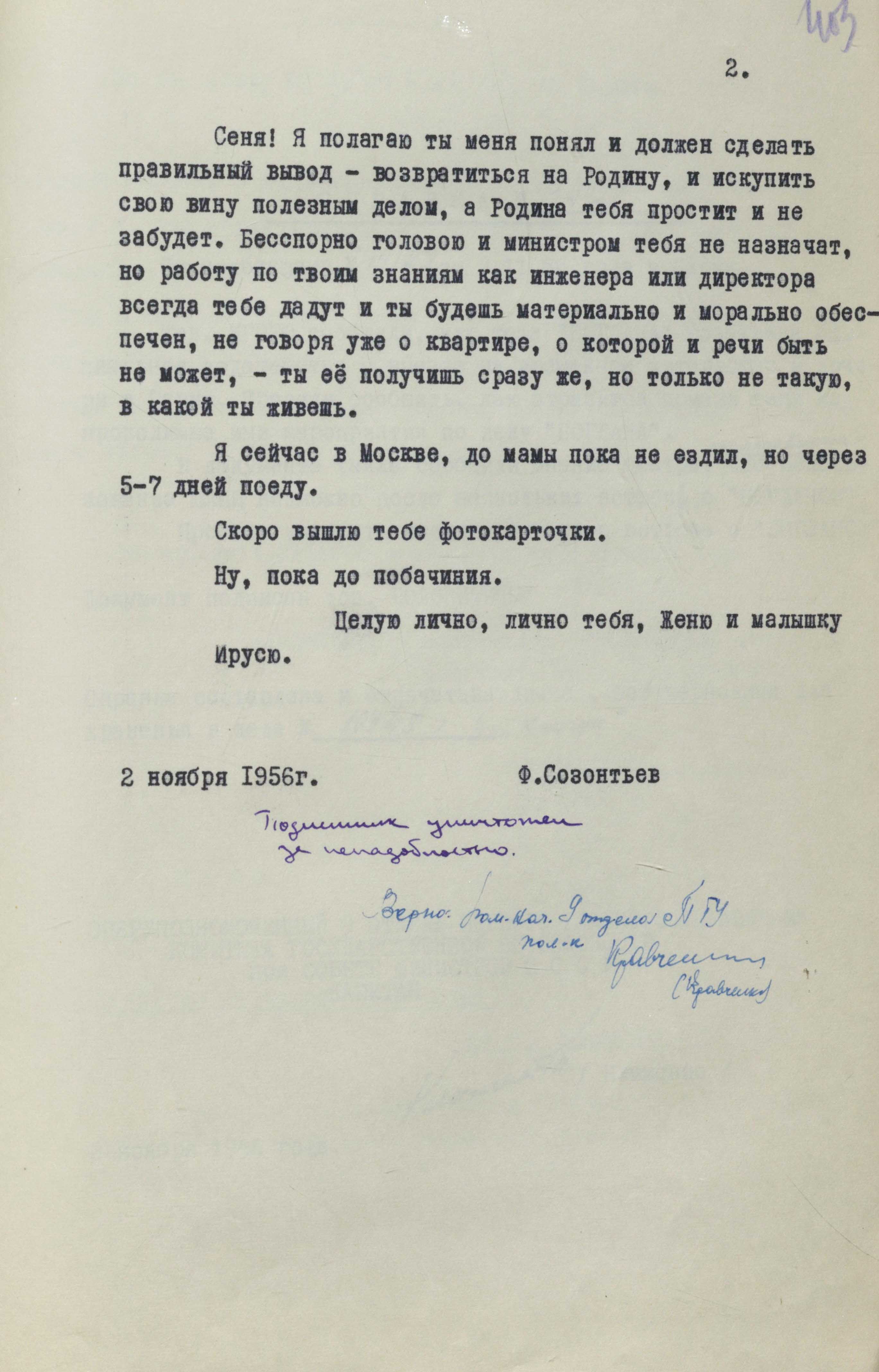

“I want to tell you once again, as a brother to a brother: give up all this and think about what is best to do and return to your homeland... They will help you with this. You have a very good and intelligent daughter, Irochka, and you must also think about her and give her a homeland... After all, if Irochka stays in France, what awaits her? She will face debauchery and abuse, for which Paris has long been famous.

Senia, I believe you understand me and should come to the right conclusion – return to your homeland and atone for your guilt by doing something useful, and your homeland will forgive you and not forget you. Of course, you will not be appointed head [of the government] or minister, but you will always be given a job that matches your knowledge as an engineer or director, and you will be financially and morally secure, not to mention a flat,– you will get it right away, and even better than the one you live in now...” (FISU – F. 1. – Case 10800. – Vol. 2. – P. 402–403).

As “Panas” wrote in his report, S. Sozontiv read the letter in front of him, snorted in dissatisfaction, and said that it was nonsense. And then he asked: “What do you want from me? First you send my brother to me, who slobbered over me, and now you come here yourself”. So, there was no substantive conversation.

After that, “Panas” came several more times, but no one opened the door. Then the “representative of the embassy” tracked down S. Sozontiv on the street and invited him for coffee. Over coffee, he asked about his health. Symon replied that he was unwell, had become prone to illness, and claimed that the reason for this was the soviet embassy’s persistent attention to him. In other words, he hinted that he might have been poisoned. “Panas” tried to calm him down, pretending to be offended, but obviously failed to persuade him otherwise.

The latest documents attached to the case state that S. Sozontiv told some leaders of the Ukrainian Revolutionary Democratic Party, of which he was a member, about his brother’s visit and the visit of an “representative of the embassy”. The URDP was headed by Ivan Bahrianyi, to whom the chekists also sent couriers to persuade him to cooperate, repent, and return to his homeland. I. Bahrianyi then resolutely rejected such approaches and told his close associates about everything, and reported it to the German police. Obviously, his party colleagues compared the events and drew certain conclusions.

One of the kgb documents states that the leaders of the URDP saw the brother’s visit as “a forced delivery by soviet intelligence for a specific purpose”. Besides, the residentura learned that S. Sozontiv had reported these meetings to the police prefecture. Consequently, moscow issued an order to stop further contacts. This happened in early 1957. At the same time, the operational cultivation continued.

One of the latest summary reports stated that at a meeting of Ukrainian nationalist organizations in France, S. Sozontiv was elected chairman of the “Committee for the Protection of Ukrainians Persecuted in the ussr”, in 1959, at the regular Congress of the “Ukrainska Hromadska Opika”, he was elected honorary chairman of the organization, headed the Ukrainian Central Public Committee in France, and was a member of the Metropolitan Council of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.

“Sozontiv was the initiator and participant of many congresses, conferences, and meetings of Ukrainian nationalists,” reads the paper, “at which he called for the unification of all Ukrainian organizations into a single organization and for establishing contacts with anti-soviet organizations of other nations for a joint struggle against soviet power.” (FISU – F. 1. – Case 10800. – Vol. 3. – P. 104).

Therefore, S. Sozontiv was constantly “looked after”. However, no active measures were planned against him. The kgb finally gave up its intentions to persuade him to return to the ussr and to bring him into contact with employees of its residentura. The chekists feared that this could lead to their arrest by the police and a high-profile scandal in the press. In 1962, a decision was made to close the case and transfer all materials to the archives. After that, S. Sozontiv continued to participate in public and political activities for another two decades. But his health no longer allowed him to do that as before.

S. Sozontiv passed away in Paris in 1980.