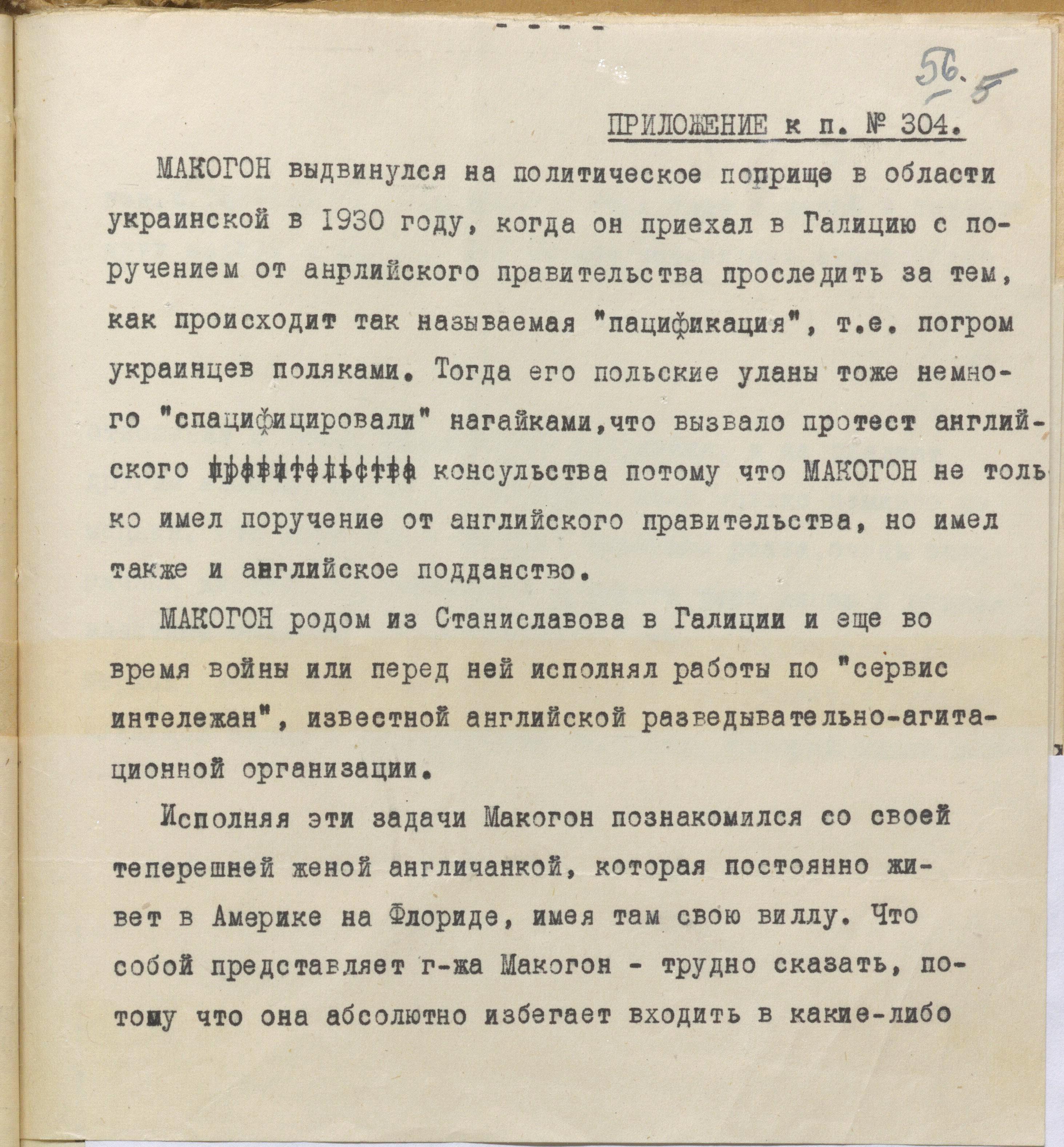

Yakiv Makohin. Founder of the “Ukrainian Press Bureau in London”

10/1/2021

Galician Yakiv Makohin, who came to Europe from the United States in the early 1930s, immediately became the object of interest of influential figures of Ukrainian emigration and Soviet intelligence. He pretended to be a retired Colonel of the US Marine Corps and a descendant of Ukrainian Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovskyi, bought villas and apartments in Italy and Switzerland, in his car with his beautiful and wealthy American wife he had traveled half of Europe, and contributed a lot to support the Ukrainian national liberation movement and to draw the world’s attention to the Ukrainian question. At this, he cultivated a halo of mystery and secrecy around his persona, which is why he was often thought to be an American, or an English, or some other spy.

Declassified archival intelligence documents partially shed light on who Yakiv Makogin really was and how sincerely he acted in the interests of Ukraine's independence. However, they are based on scattered testimonies of people who did not know him very well, on intelligence reports, as well as assumptions and conclusions of agents of the NKVD of the USSR, often contradictory, and this does not allow to form a holistic picture of his life and work. Nevertheless, Ya. Makohin, until recently almost unknown to the general public, is an extremely interesting and noteworthy figure in the Ukrainian history of the time, and his ascetic work on supporting and promoting Ukrainian interests deserves due appreciation from today's standpoint.

The online encyclopedia “Ukrainians in the United Kingdom” provides brief information about Yakiv Makohin. “Jacob (Yakiv) Makohin”, the biographical reference reads, “is a Ukrainian-American military, public figure and philanthropist; he was born September 27, 1880, probably in the village of Vyazova (Zhovkva district, Lviv region, Ukraine; at that time - Zhovkva povit, Austrian Galicia); died January 13, 1956 in Boston, Massachusetts, USA; buried in Arlington National Cemetery (Virginia, USA)”.

The online encyclopedia “Ukrainians in the United Kingdom” provides brief information about Yakiv Makohin. “Jacob (Yakiv) Makohin”, the biographical reference reads, “is a Ukrainian-American military, public figure and philanthropist; he was born September 27, 1880, probably in the village of Vyazova (Zhovkva district, Lviv region, Ukraine; at that time - Zhovkva povit, Austrian Galicia); died January 13, 1956 in Boston, Massachusetts, USA; buried in Arlington National Cemetery (Virginia, USA)”.

It is noted that in 1903 he emigrated to the United States, and from 1905 to 1921 he served in the US Marine Corps. In 1917 he got American citizenship. During World War I, as well as later, according to the encyclopedia, he may have worked for American intelligence. This assumption is confirmed only by the postscript “according to some sources”. But there is no documentary evidence of this.

It is noted that in 1903 he emigrated to the United States, and from 1905 to 1921 he served in the US Marine Corps. In 1917 he got American citizenship. During World War I, as well as later, according to the encyclopedia, he may have worked for American intelligence. This assumption is confirmed only by the postscript “according to some sources”. But there is no documentary evidence of this.

In 1920, he married Susan F. Fallon (1891–1976), the daughter of a wealthy American Admiral. Some publications claim that she was willing to accept and always supported the version that Yakiv was the only descendant of the Cossack Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovskyi, although there was no evidence of this. At the same time, the couple showed great ambitions and aspirations to be equal in the society, their exclusiveness and mystery.

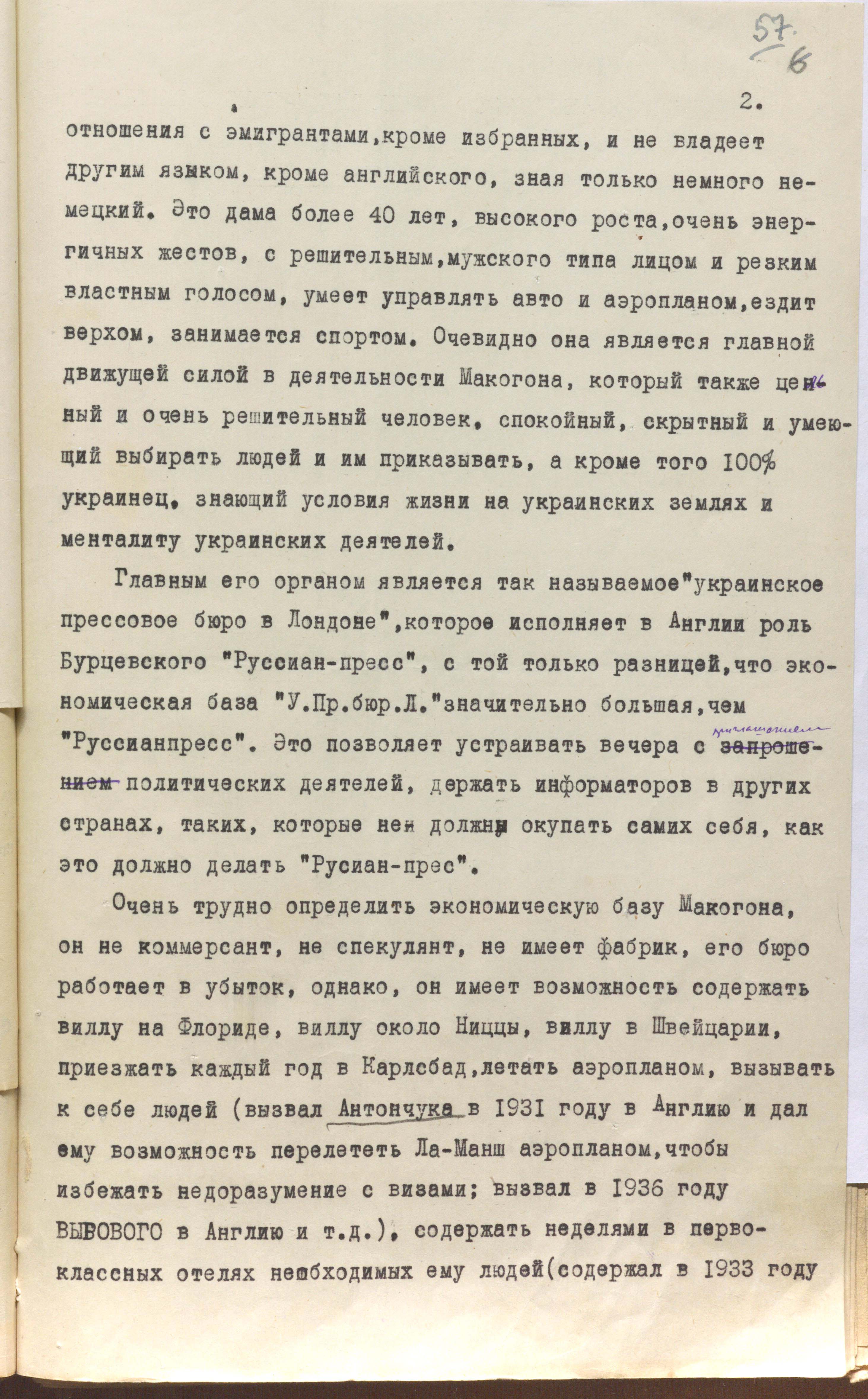

“It is difficult to say who Mrs. Makohin is”, says one of the archival documents, “because she completely avoids relations with emigrants other than the chosen ones and does not speak any language other than English, she only knows German a little”. She is a lady over 40 years old, tall, with quite energetic gestures, with a determined, masculine face and a sharp authoritative voice, knows how to drive a car and an airplane, rides a horse, goes in for sports. Obviously, she is the main driving force in the activities of Makohin, who is also an agile and very determined man, calm, secretive, able to attract people and order them, and being a one hundred percent Ukrainian, knows the living conditions in Ukrainian lands and the mentality of Ukrainian figures” (BSA of the SZR of Ukraine.— F. 1. - Case 9770. – P. 56–57).

Given the fact that Makohin emigrated to the United States at the age of 23, he already had a formed character at that time and managed to absorb his love for the Ukrainian land, culture and history. This is evidenced by his entire subsequent life. Overseas, he tried to closely monitor the events taking place in his homeland. He worried about the hard living conditions in Western Ukraine, the oppression of the Ukrainians’ rights.

Given the fact that Makohin emigrated to the United States at the age of 23, he already had a formed character at that time and managed to absorb his love for the Ukrainian land, culture and history. This is evidenced by his entire subsequent life. Overseas, he tried to closely monitor the events taking place in his homeland. He worried about the hard living conditions in Western Ukraine, the oppression of the Ukrainians’ rights.

In 1923 and 1930, he and his wife traveled to Europe for several weeks to learn how his countrymen lived. He talked to leading Ukrainian politicians from among the supporters of the governments of the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Western Ukrainian People's Republic in exile. He visited his native Galicia, met with activists of the Ukrainian National Democratic Union. His trip was reflected in the documents of the NKVD of the USSR. One of the special reports stated: “Arrived from Lviv in Chernivtsi in his own car accompanied by my wife, driver and secretary. Then - by car – went to Bucharest, then to Bulgaria, Budapest”(BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. – P. 42).

Makohin took a lot of photos, talked to locals, wrote down his impressions, bought ancient icons, carpets, embroidered shirts. What he saw excited him greatly. Back in the United States, he prepared and published at his own expense a collection of materials about the needy life of Ukrainians translated into English and French. Published in large numbers and distributed in many countries around the world, the book attracted the world community’s attention to the Ukrainian issue.

At the same time, he began to spread among Ukrainians in North America the idea of uniting the efforts of all Ukrainian emigration organizations to hold an information and political action in Europe, which he was ready to sponsor. Soon the idea arose to establish a press office in one of the European capitals, which would collect and spread among different countries true information about Ukrainian people, their fate and centuries-old desire to have their own independent state, about the living conditions of the time.

Mykola Tymoshyk, Doctor of Philology, Professor, Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Higher School of Ukraine, spoke in detail about the first concrete steps on this path and in general about Yakiv Makohin’s multifaceted ascetic activity. According to his research, at the end of January 1931, Makohin wrote to leading Ukrainian figures in different countries, as well as Galicia and Bukovina, with a specific proposal, which consisted actually of two points:

1. He is ready to allocate for two years his own funds for the establishment of the Ukrainian Press Bureau, until the Ukrainian emigration accumulates during this time the amount needed to ensure the continued existence of such an institution.

2. The main and constant point of the program activities of the bureau should be: indifference to politics and avoidance of any group; the bureau should serve not a party, a group of individuals or an individual, but the entire Ukrainian community.

Yakiv Makohin then bought an old two-story building in central London. The inscription in Ukrainian and English “The Ukrainian Bureau in London” soon appeared on it. In November 1931 he founded a branch of the Ukrainian Bureau in Geneva, and in January 1932 in Prague. He invited the well-known historian and sociologist Volodymyr Kysylevskyi, a former legionnaire of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen who had defended his doctorate at the University of Vienna, received Canadian citizenship, and was editing the “Western News” Ukrainian Catholic weekly in Edmonton.

The work of the Bureau was to collect, analyze and summarize everything that was published in the world press about Ukraine, and to prepare on this basis information reports, bulletins and brochures. They were translated into different languages, printed in large numbers and sent free of charge around the world. The Bureau also cooperated with foreign journalists and British parliamentarians, supported charitable projects aimed at protecting Ukrainians abroad. In particular, Makohin provided financial support to the Museum of the Liberation Struggle of Ukraine in Prague, donated funds for Ukrainian scientific and cultural events, publishing, business trips abroad of scientists from Western Ukraine, scholarships for students and more.

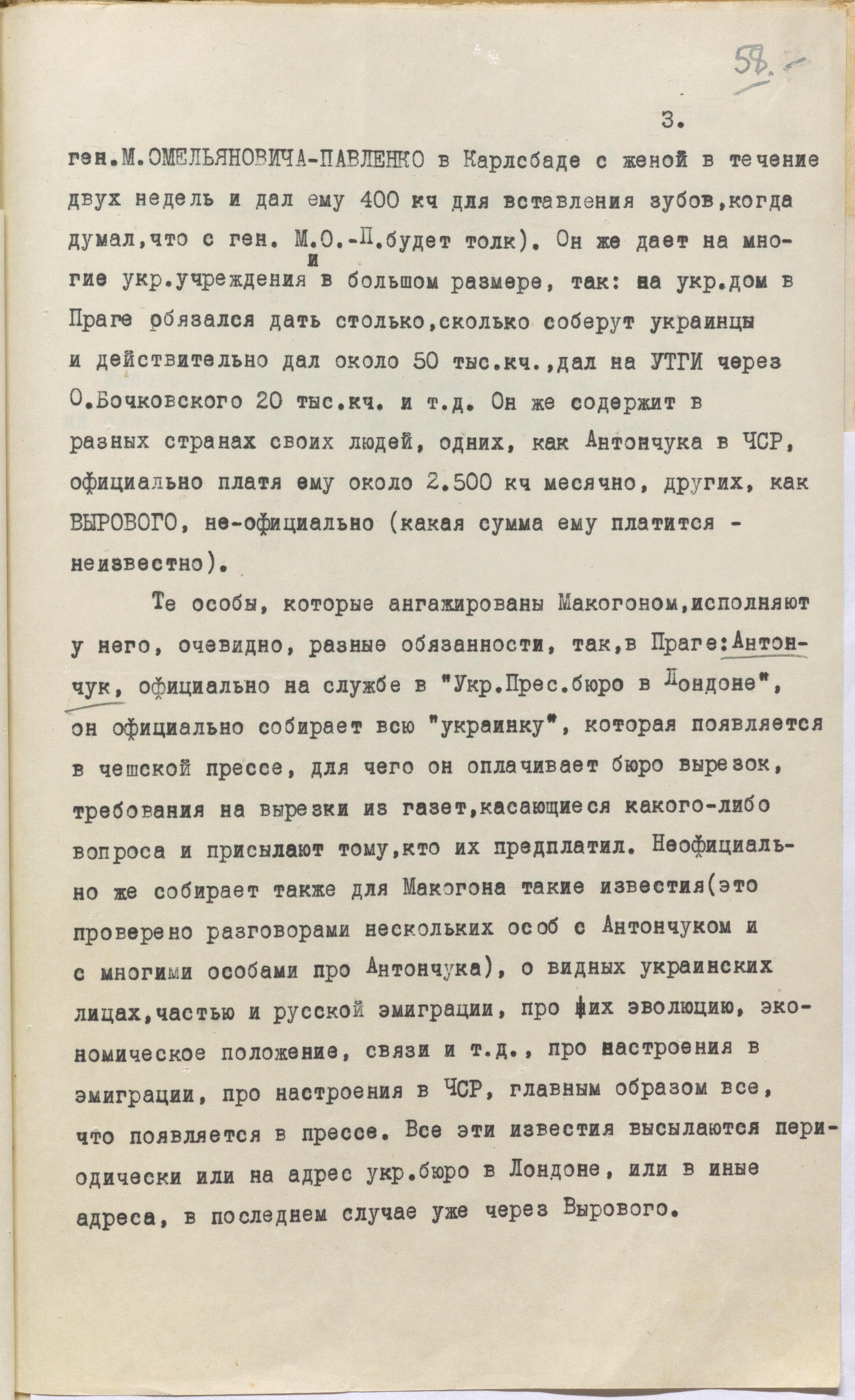

This activity and its financing are repeatedly mentioned in the Intelligence’s archival documents. For example, one of them reads: “It is very difficult to find out the economic base of Makohon, he is neither a businessman, nor a profiteer, he has no factories, his office is unprofitable, but he can afford a villa in Florida, a villa near Nice, a villa in Switzerland, annual travelling to Carlsbad, flying by plane, inviting people (invited Antonchuk in 1931 to England and gave him the opportunity to cross the English Channel by air to avoid misunderstandings with visas; in 1936 he invited Vyrovyi to England), sponsors the needed by him people’s staying for weeks in first-class hotels (in 1933 was paying for General M. Omelyanovych-Pavlenko’s staying in Carlsbad with his wife for two weeks and gave him 400 Czech crowns for dental prosthetics, when he thought that Gen. M. O-P would be useful). He also gives a lot to Ukrainian institutions and in large amounts, for example: He promised to give the Ukrainian House in Prague as much as the Ukrainians themselves would collect, and in fact gave about 50 thousand Chech crowns… He supports his people in different countries, some like Antonchuk in Czechoslovakia, officially giving him a salary of about 2,500 Check crowns a month, others, like Vyrovyi, unofficially (the sum paid is unknown) (BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. - Case 9770. - P. 57–58).

According to archival documents, at that time Ya. Makohin lived mostly in Switzerland and Italy. From time to time he visited Great Britain to resolve urgent matters. And then he did not miss the opportunity to meet with Yevhen Lyakhovych, who was in London in the mid-1930s as a representative of the OUN and sought the British government’s support for the Ukrainian liberation movement.

In fact, Ye. Lyakhovych and Ya. Makohin complemented each other with their activities. Thus, from the first months of his stay in London, Ye. Lyakhovych developed an active information work - he appeared with articles in the British press and spread materials about Ukraine among British journalists. He soon wrote a pamphlet in English entitled “The Ukrainian Question” on about fifty typewritten pages. In doing so, he tried to fill the gap in the UK's lack of political literature on Ukraine in English. He also contacted British parliamentarians and journalists to draw attention to the Ukrainian issue through them. Especially fruitful were his relations with the well-known British international journalist, military, historian, economist, scientist engaged in Ukrainian studies and public figure Lancelot Lawton.

Similarly, through the Ukrainian Press Bureau in London, Ya. Makohin was spreading information about Ukraine and worked through British diplomats and journalists. At the same time, unlike Ye. Lyakhovych, he had a powerful financial resource, which allowed him to attract more opportunities and a wider range of people. The Bureau purchased newspapers, magazines and bulletins at its own expense, including Ukrainian periodicals from Galicia, Bukovina and Transcarpathia, new Ukrainian books published in America and Western Europe, as well as publications of scientific and educational institutions of Ukrainian emigration. “As a result of conversations with Ya. Ye. Makohon”, Yevhen Lyakhovych later recalled, “we decided to cooperate in London without losing our separate positions, that is, his of a sponsor of private information bureaus and mine of a representative of the political movement.( in the case file, the spelling “Makohon Yakiv Yukhymovych” is repeatedly used. - Note).

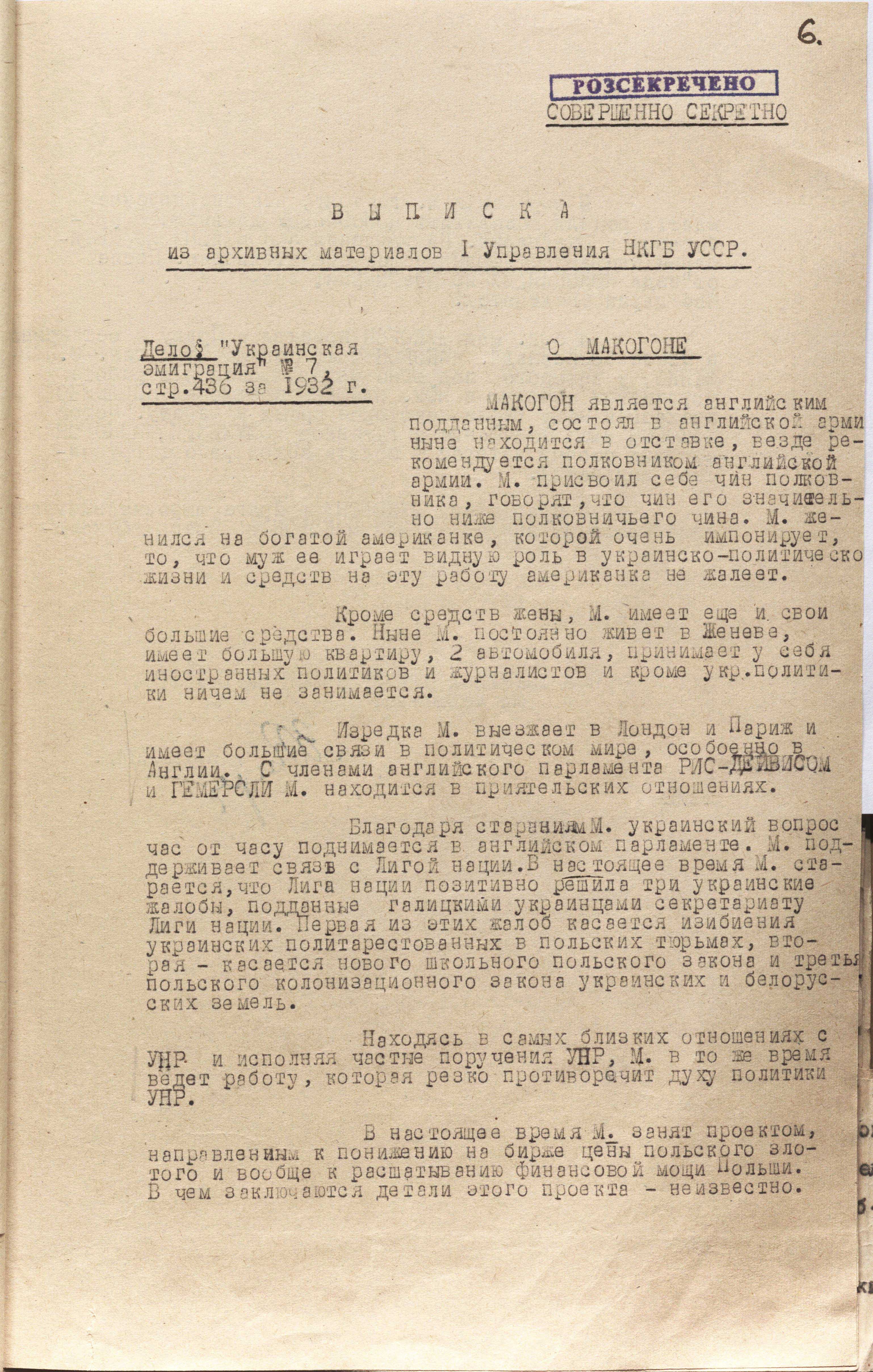

Ya. Makohin had supporters and followers in both Houses of the British Parliament. An archival document of 1932 mentions his contacts: “He has great contacts in the political world, especially in England. He is friends with members of the English Parliament Reis-Davis and Gemersley. Thanks to M.'s efforts, the Ukrainian issue is periodically raised in the English Parliament. M. maintains ties with the League of Nations. At present, M. is trying to get the League of Nations to resolve positively the three Ukrainian complaints submitted by Galician Ukrainians to the Secretariat of the League of Nations ”(BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. - P. 6).

Archival documents repeatedly mention Ya. Makohin's meetings with politicians in Rome, Prague, Geneva, Paris and other countries, his contacts with influential figures of Ukrainian emigration — Yevhen Konovalets, Yevhen Onatskyi, Andriy Livytskyi and others. In particular, this concerns the leader of the UPR government in exile A. Livytskyi’s intention to meet with him. “It is high time to contact with the famous Makohin”, reads the special report of the Foreign Department of the USSR ODPU of December 5, 1933, “who has English acquaintances”. Livytsky himself has no English acquaintances and wants to use Makohin's… Contact with Makohin is needed badly by Livytskyi” (BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. – P. 28).

Archival documents repeatedly mention Ya. Makohin's meetings with politicians in Rome, Prague, Geneva, Paris and other countries, his contacts with influential figures of Ukrainian emigration — Yevhen Konovalets, Yevhen Onatskyi, Andriy Livytskyi and others. In particular, this concerns the leader of the UPR government in exile A. Livytskyi’s intention to meet with him. “It is high time to contact with the famous Makohin”, reads the special report of the Foreign Department of the USSR ODPU of December 5, 1933, “who has English acquaintances”. Livytsky himself has no English acquaintances and wants to use Makohin's… Contact with Makohin is needed badly by Livytskyi” (BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. – P. 28).

Another document for 1931 states:

“The famous British agent Makohin made in May and June a trip to Europe to negotiate with right-wing groups of Ukrainian emigrees and unite them for joint action.

Makohin negotiated with Hetmanites, Ukrainian nationalists and well-known Petliurites, expressing the need to organize a single governing center. Only if the Ukrainian organizations accept this proposal, they can count on the full support of British politicians” (BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. - P. 3).

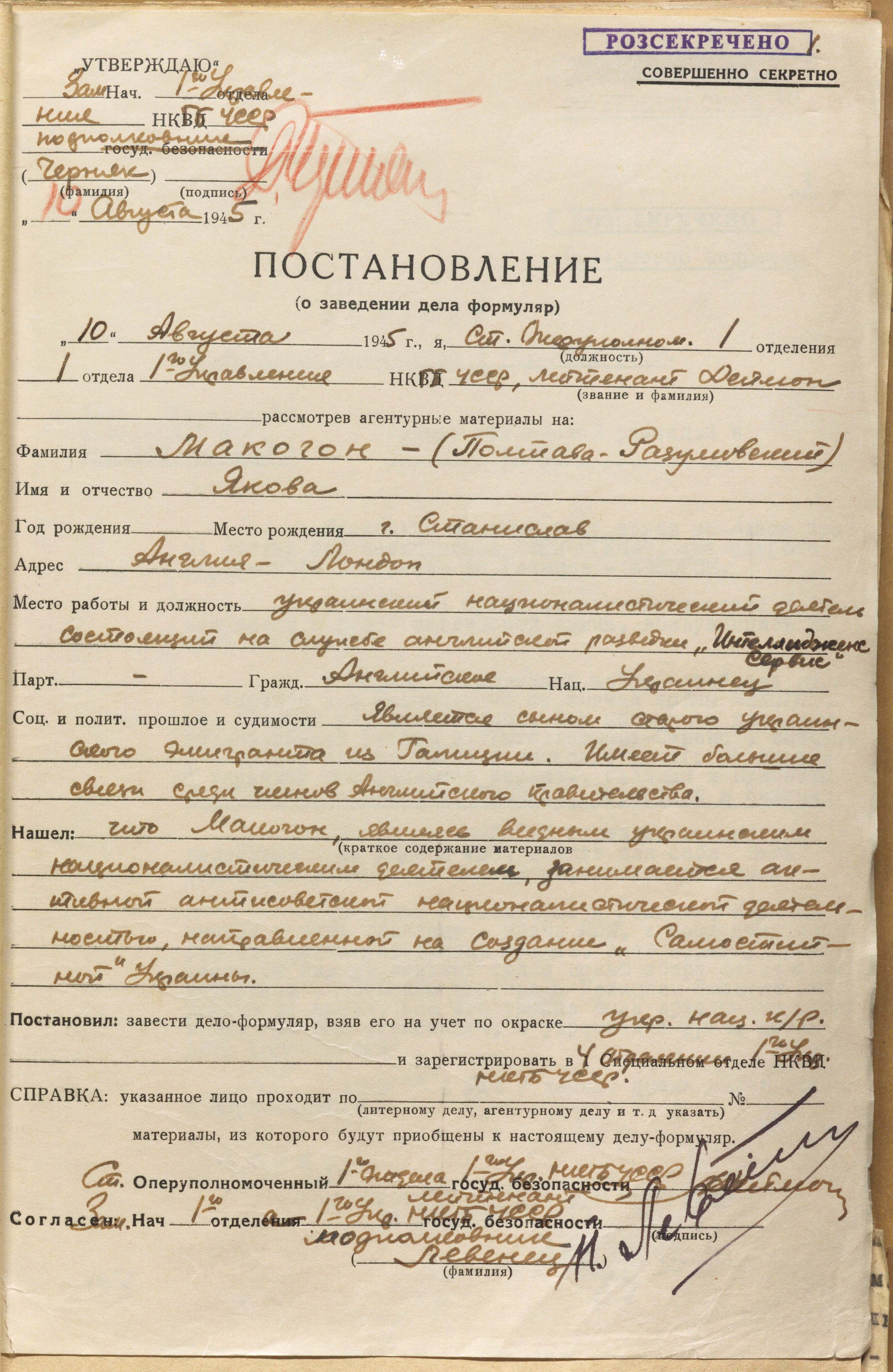

There is nothing special about the GPU documents mentioning Ya. Makohin as an English agent. At that time, almost all activists of the Ukrainian emigration were in the materials of operational cases as agents of foreign intelligence. Yakiv was often called an English and American spy. In particular, a former resident of “Intelligence Service” in Lviv. The resolution to file a case against him reads as follows: “Place of work and position: Ukrainian nationalist figure working for the British “Intelligence Service".

Besides, he was even called a Polish agent, which was absolutely contrary to logic and common sense, given his attitude to the then Poland’s policy in Western Ukraine. One of the documents mentions him as a combined American-Polish agent. “Makohin's Geneva, London and Paris bureaus”, the document said, “are intelligence offices for Poles and Americans. The Poles subsidize the UPR through Makohin. Makohin's money is also provided by the Americans ”(BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. - P. 25).

Besides, he was even called a Polish agent, which was absolutely contrary to logic and common sense, given his attitude to the then Poland’s policy in Western Ukraine. One of the documents mentions him as a combined American-Polish agent. “Makohin's Geneva, London and Paris bureaus”, the document said, “are intelligence offices for Poles and Americans. The Poles subsidize the UPR through Makohin. Makohin's money is also provided by the Americans ”(BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. - P. 25).

Finally, after a series of reports and inquiries in this regard, in October 1935, the Foreign Department of the State Security Directorate of the NKVD of the Ukrainian SSR came to the following conclusion: “British intelligence is especially interested in him. Romanians suspect that Makohin is a Soviet agent, while the British tend to assume two options: either he is an American intelligence agent or an ordinary political adventurer who acts at his own discretion as long as he has enough money” (BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F. 1. – Case 9770. - P. 43).

Evidently, such conclusions were prompted by Ya. Makohin’s lifestyle and, not least, adventurism. For example, the documents state that in 1934 he and his wife crossed the Polish-Ukrainian border with forged Hungarian passports and spent several days in Soviet Ukraine near Chernivtsi, where they got acquainted with the living conditions of Ukrainians. Other documents, citing Susan Fallon, say there were quite a few such border crossings.

During his travels in Europe, Yakiv Makohin liked to mention that he was a Colonel of reserve, although in fact, according to archival documents, he only served as a Captain. While the words on the tombstone say “Second Lieutenant” – i.e. the primary military rank of officer in the US Armed Forces. Besides, he worked under various names and surnames, such as Makukhin, Makhonin, Men-Ogen, Jack McOwen. And also - Poltava-Rozumovskyi. He called himself the successor of the Cossack Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovskyi and a contender for the Ukrainian throne in case of restoration of an independent Ukrainian state.

And this also to some extent left an imprint on his perception by the environment and special services. At the same time, despite his undisguised ambitions, attempts to demonstrate his allegedly high status in the society and spending a lot of money on villas, apartments, planes, cars and an elite lifestyle, he sacrificed a lot for the Ukrainian cause.

As Professor Mykola Tymoshyk points out in his studies, Yakiv Makohin, in addition to financing the activities of the Ukrainian Press Bureau in London and several of its branches in other countries, contributed a significant amount of his own money to the construction of the Ukrainian House in Prague. The Bureau became a sponsor and patron of the Ukrainian Plast publishing house, which was founded in Prague in 1933. The Ukrainian Bureau was a collective member and financially supported a number of Ukrainian scientific, publishing and cultural societies, such as Supporters of the Ukrainian Academy of Economics in Podebrady, Sich, Supporters of Ukrainian Song, Supporters of Ukrainian Books, the Union of Ukrainian Journalists and Writers and others.

After two years of the Ukrainian Bureau’s hard work, the disparate circles of Ukrainian emigrants faled to accumulate funds for further financing of the project. Yakiv Makohin continued to take care of it for several years. Soon, according to open sources, he went bankrupt and suspended his work. At the beginning of World War II he lived in Alassio (Italy), from where he left for the United States in 1940 or 1941. There he retired from active political life and lived on his ranch.

After the World War II, the MGB of the USSR tried to revive the case of Yakiv Makohin. In August 1945, a corresponding case-form was instituted. But seven years later, a decision was made to stop his cultivation “due to lack of intelligence capabilities”.

Yakiv Makohin died on January 13, 1956 in Boston. Buried in Arlington National Cemetery. After his death, his colleague in the national liberation struggle, Yevhen Lyakhovych wrote in the article “The OUN's Activities in London in 1933–1935”: “Frequent conversations with Ye. Makohin and his wife, who were especially active in the affairs of Ukrainian bureaus, wore off my distrust of them. I was convinced of their good will and desire to help Ukrainians in their quest for an independent state. That help, of course, could only come from the means they had. Ya. Makohin often repeated: “The most important thing is the cause of liberation; everything else must be subordinated to it”. “ I never had and now do not have any reason to doubt his honesty”.

Yakiv Makohin died on January 13, 1956 in Boston. Buried in Arlington National Cemetery. After his death, his colleague in the national liberation struggle, Yevhen Lyakhovych wrote in the article “The OUN's Activities in London in 1933–1935”: “Frequent conversations with Ye. Makohin and his wife, who were especially active in the affairs of Ukrainian bureaus, wore off my distrust of them. I was convinced of their good will and desire to help Ukrainians in their quest for an independent state. That help, of course, could only come from the means they had. Ya. Makohin often repeated: “The most important thing is the cause of liberation; everything else must be subordinated to it”. “ I never had and now do not have any reason to doubt his honesty”.

(Picture of Ya. Makohin from the archives of Mykola Tymoshyk)