Ilko Borshchak. At the Cutting Edge of soviet Special Propaganda in France

3/28/2025

Declassified documents of the ogpu/nkvd of the ussr of the 1920s and 1930s from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine show that at that time the kremlin leadership had been making great efforts through its special services to promote soviet ideology around the world and to influence the labor movement abroad, the mood in the emigration community, and the world public opinion in general. Former compatriots with exorbitant ambitions, talented and authoritative individuals, and at the same time prone to all kinds of adventures, were often chosen to carry out such plans and act as agents of influence. Ilko Borshchak was one of them in France.

Who Are You, Monsieur Borshchak (Barshak)?

In the 1920s, even before the establishment of diplomatic relations between France and the ussr, soviet intelligence agents were already active in Paris. Soon, the residentura of the ogpu was making sure everything worked as the kremlin needed it to. Special attention was paid to the white-emigrant monarchist movement and physical liquidation of former generals of the russian imperial army. In parallel, a separate line of work was devoted to tracking Ukrainian emigrant organizations, in particular the figures of the UPR led by Symon Petliura.

Those Ukrainians who, after the defeat of the Liberation Movement, were forced to emigrate to France, created a number of socio-political organizations which advocated restoration of the independence of the Ukrainian state and criticized the soviet system. moscow perceived them as anti-soviet. Therefore, through diplomatic and other institutions, and especially through the residentura of the ogpu, they sought to create a kind of parallel structures that would sow discord in the Ukrainian national liberation movement abroad, hold meetings in support of the ussr, and persuade emigrants to return to their homeland, where everyone would allegedly be guaranteed a happy life, freedom and prosperity.

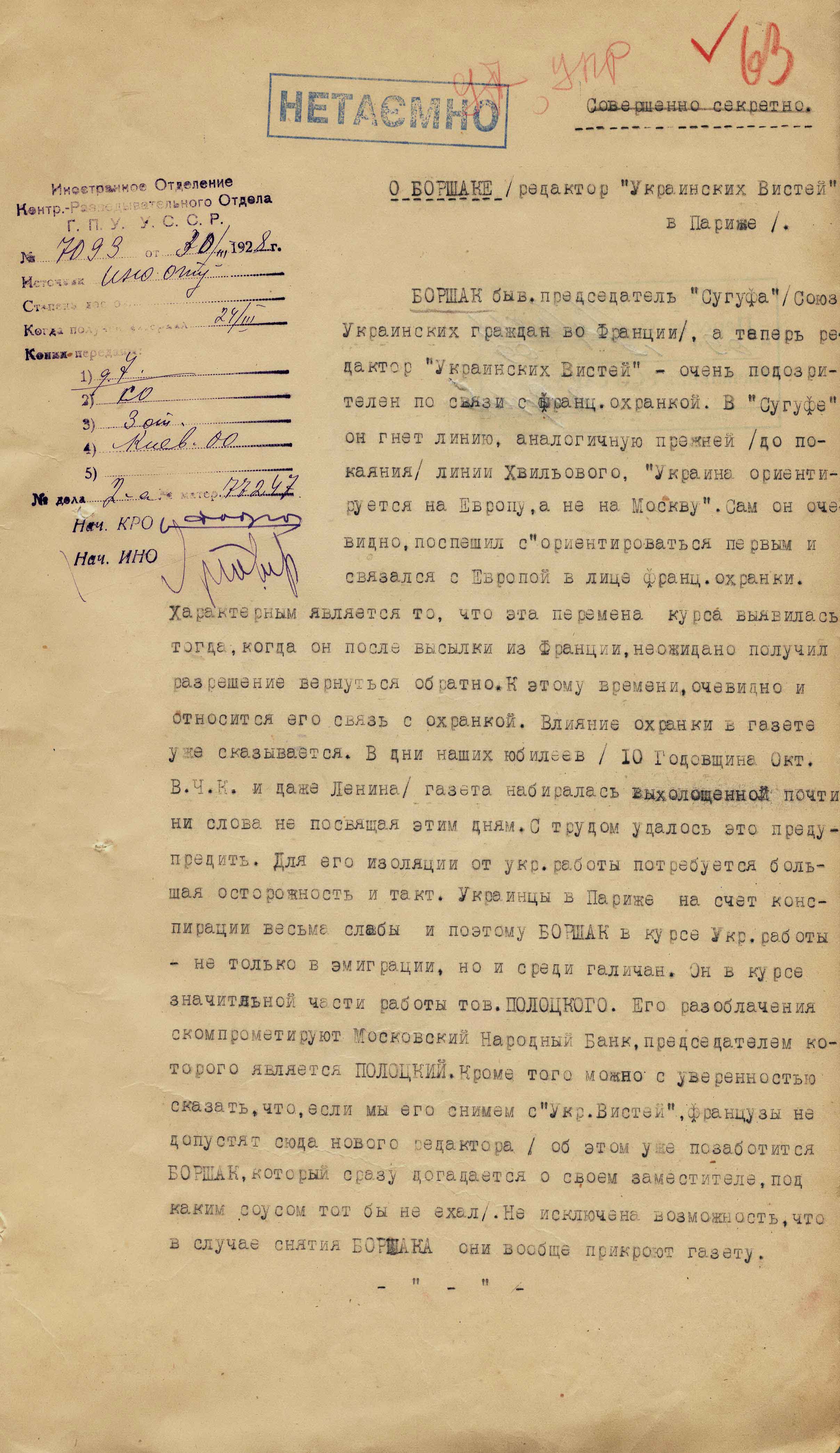

One such organization was the sovietophile Union of Ukrainians of France (SUHUF). In 1925, Ilko Borshchak became its co-founder and Secretary General. Among the archival documents that were once sent from the residentura in Paris to moscow and then to Kyiv for further operational cultivation of I. Borshchak, there is no information on when exactly he drew the chekists’ attention. At the same time, generalized reports mention that in the first half of the 1920s he was in contact with the staff of the ogpu residentura.

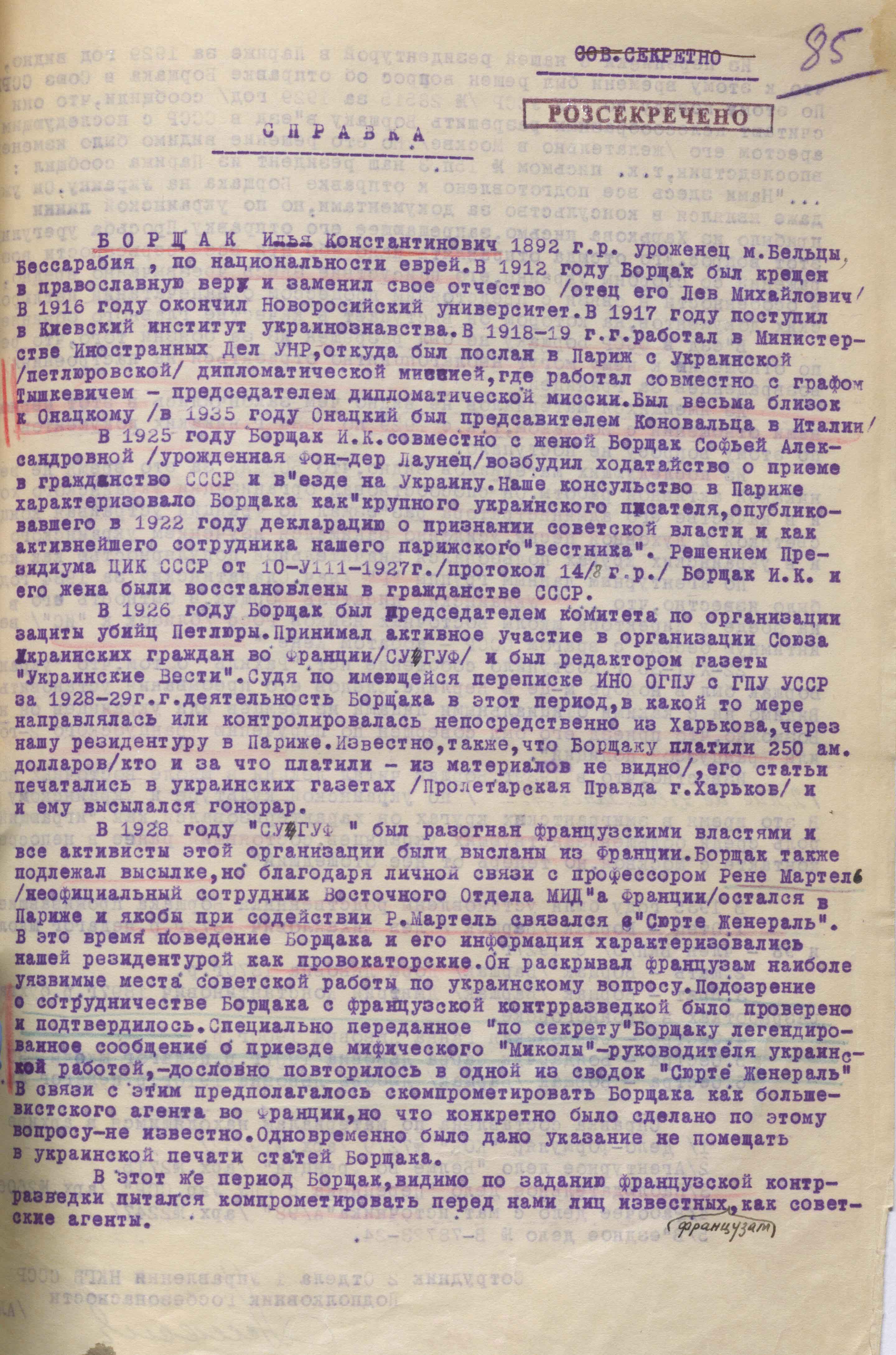

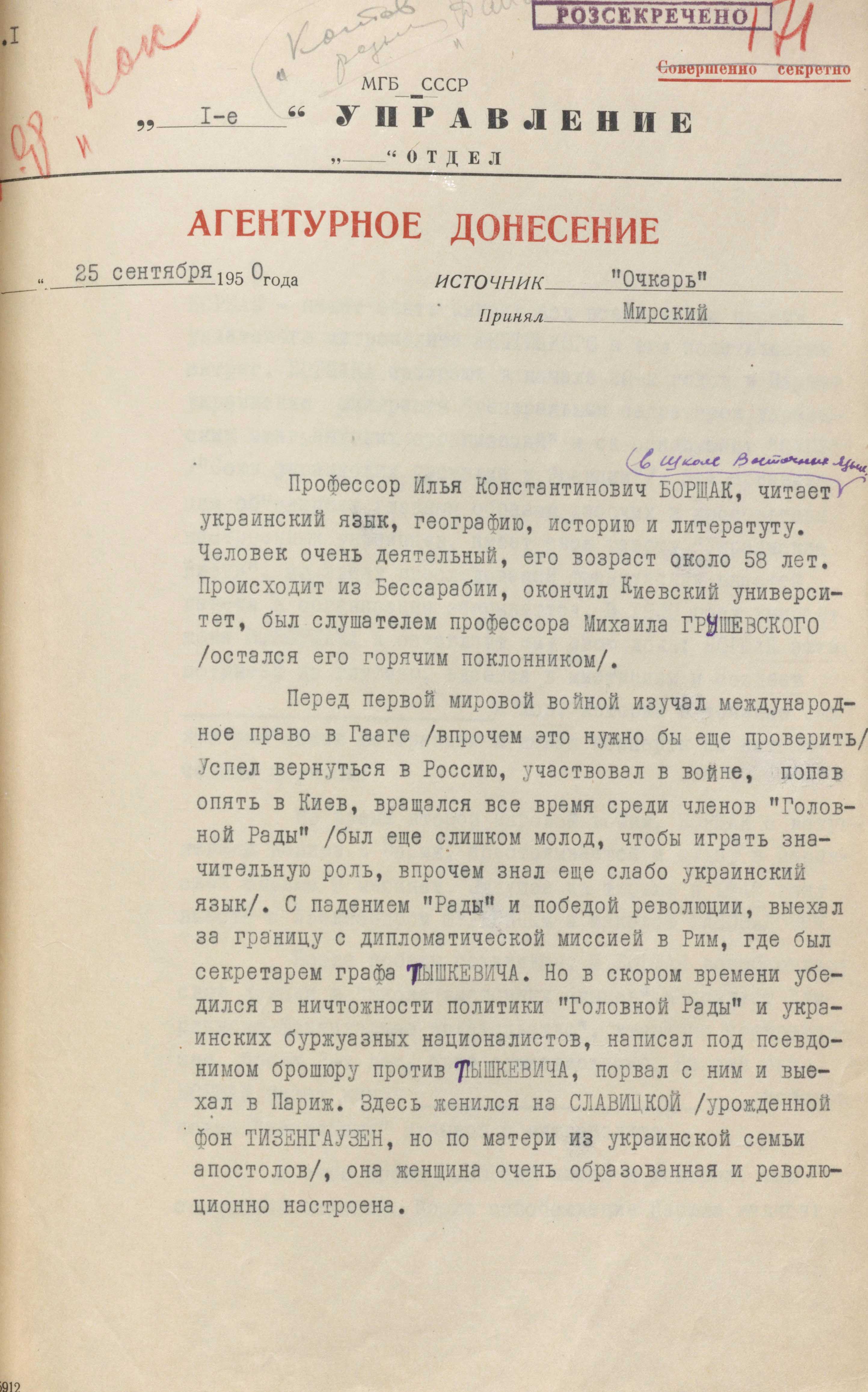

The study of I. Borshchak, as well as other objects of interest of the ogpu, began with the collection of information about his life in the ussr before emigration. At the same time, inquiries about his place of birth and close relatives were answered with a delay. It soon became clear that the reason was the different spelling of his surname and patronymic. One of the papers written by the chekists on the basis of the information collected by foreign agents states that he originated from the town of Beltsi in the Bessarabian province of the russian empire (now the Republic of Moldova), was Jewish by nationality, born in 1892 (in fact, on July 19, 1894). His father was Lev (Leib-Hersha) Mykhailovych Barshak. At the age of eight, Illia was converted to Christianity (the Orthodox faith) and at the same time his father’s name was changed to Kostiantynovych. This was done allegedly in order to avoid problems with admission to higher education institutions. As a result, he managed to enter Novorossiysk University in Odesa without any problems.

At the same time, as researchers of I. Borshchak’s life and work, including Professor of History at the Ukrainian Catholic University Vadym Adadurov, have now discovered, he made up many fables in his stories about himself abroad. He told about his birth in the Orthodox faith in Kherson in 1891 or 1892, a research trip to Europe in 1914, his detention by the Germans and return to russia via Norway, his fighting on the fronts of World War I from September 1914 to February 1918, two wounds, being awarded a St. George Cross, and his promotion to an officer. In reality, he did not fight a single day.

Later, in exile, he posed as a professional scholar, without providing any proof of his academic degrees. He explained that they had burnt in the flames of the revolutionary events of the 1917-1920s. At the same time, he began to change the spelling of his name. At first he spelled his name as Borchak, but since 1920 he had been writing it as Ilko Borschak. He was engaged in research in French archives and, based on the documents he found and which related to Ukrainian history, he published articles and books about Ivan Mazepa, Pylyp and Hryhir Orlyks, Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, Napoleon and Ukraine, and so on, which were interesting in content but with a fair share of fiction and speculation, and sometimes even fake. This gave current researchers reason to call him a master of historical mystifications.

But the soviet mission looked at his work from a different point of view. One of the ogpu’s papers reads as follows: “Our consulate in Paris characterized Borshchak as a great Ukrainian writer who in 1922 published a declaration recognizing soviet power and as the most active employee of our Parisian newspaper, “Visnyk”. At this, it was pointed out that “in 1925, I. K. Borshchak and his wife, Sophia Oleksandrivna Borshchak (née von der Launitz), applied for ussr citizenship and entry to Ukraine” and that by a decision of the presidium of the central executive committee of the ussr on August 10, 1927, they were granted ussr citizenship (FISU – F. 1. – Case 6738. – P. 85).

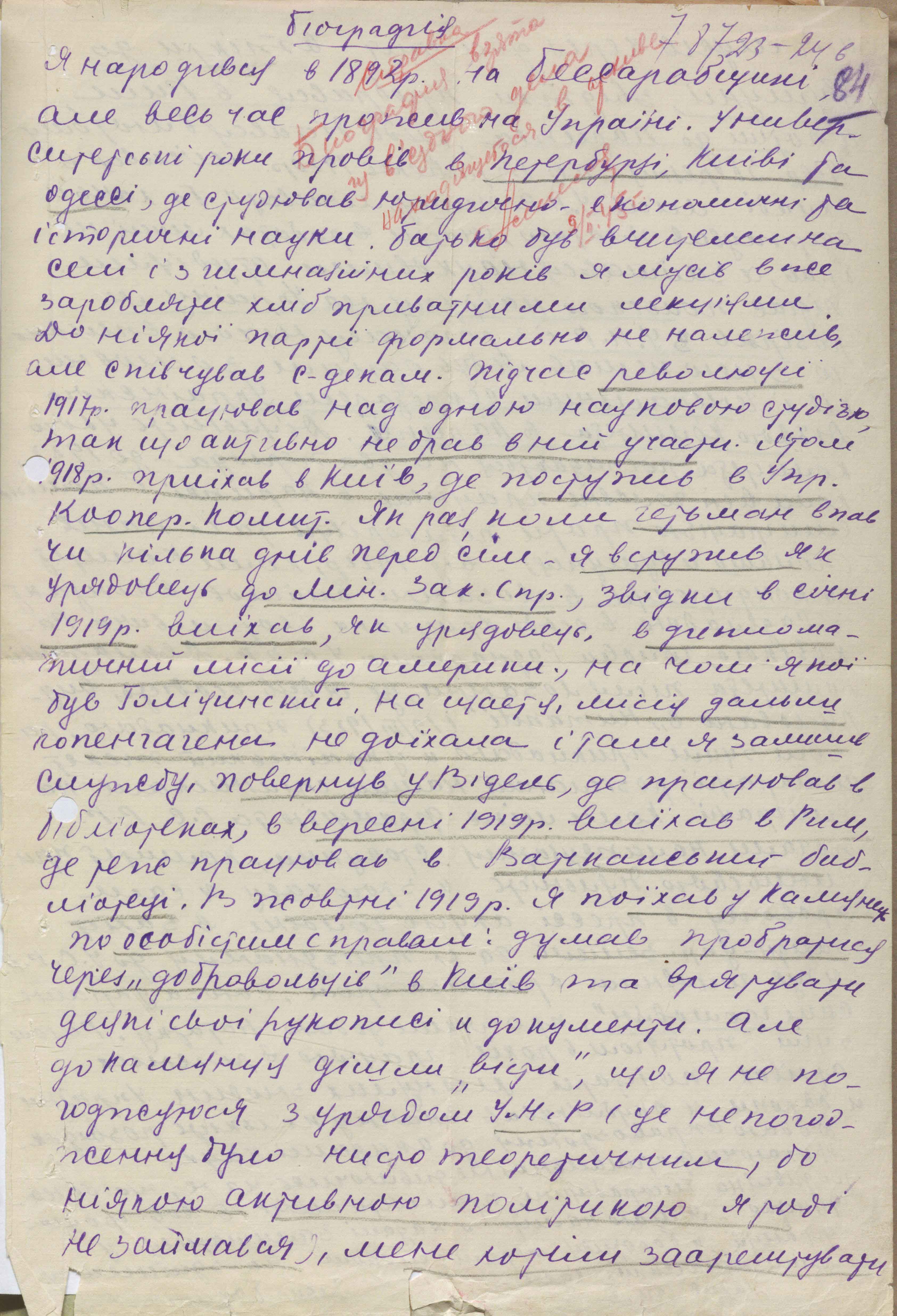

Among the archival documents there is I. Borshchak’s handwritten application request for citizenship. In it, he stated that although he was born in Bessarabia, he had lived in Ukraine all his life. He did not take part in the 1917 revolution because he was allegedly working on a scientific study at the time. During the Hetmanate, he served in the Ukrainian Cooperative Committee and in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Ukrainian State. In his words, in January 1919 he was supposed to leave for America as part of a diplomatic mission, but the mission only made it to Copenhagen. There he left the government service and went first to Vienna and then to Rome, where he did some research in libraries, including the Vatican Library. Soon after, he made an attempt to get to Kyiv through the front of Anton Denikin's Volunteer Army, but without success. In February 1920, he found himself in Paris.

“From March to May 1920,” he wrote, “I was considered to be a member of the UPR mission. I write “was considered to be” because, although I was receiving a salary, I did not participate in the mission’s work but was engaged in scientific research. During the Polish offensive against Ukraine, I broke with the UPR and since then have had nothing to do with it” (FISU. – F.1. – Case 6738. – P. 84).

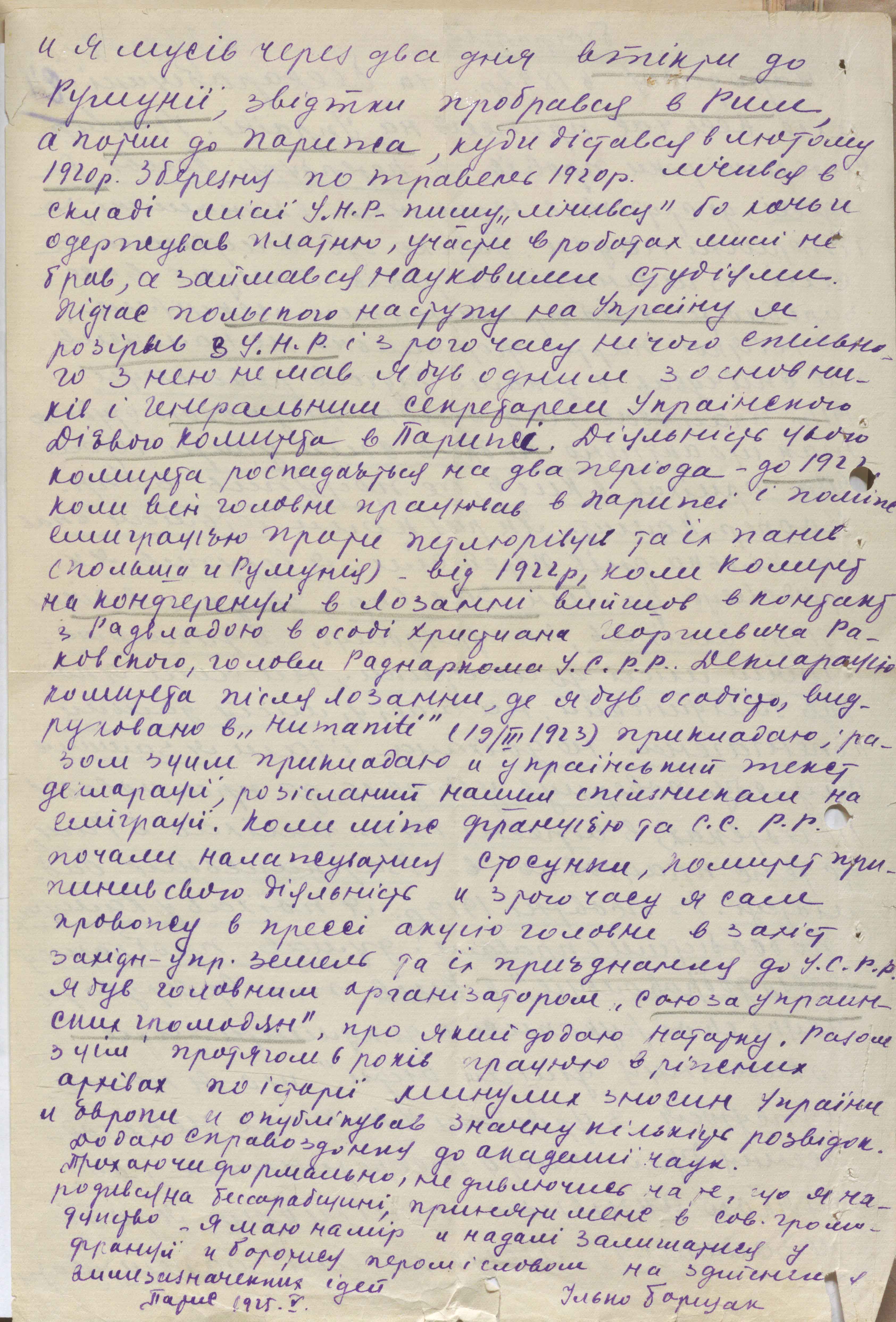

He made such statements in order to dissociate himself from the UPR in every possible way and to please the employees of the soviet mission in France. Eventually, it happened as he planned. In addition, in his petition, he reported that he was one of the founders and Secretary General of the Ukrainian Action Committee in Paris and, on behalf of the Committee, in 1922, during an international conference in Lausanne, he got in touch with a representative of the soviet government, Khrystyian Rakovskyi, the then head of the council of the people’s commissars of the Ukrainian ssr. At the same time, he prepared a declaration of recognition and support for the soviet government, which was soon published in the French communists’ newspaper L’Humanite.

There is no information in the archival documents about what exactly he was agreeing with H. Rakovskyi, what was demanded from him, and what he promised to do in exchange for citizenship. But immediately after returning from Lausanne to Paris, I. Borshchak founded the Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France and became its Secretary General.

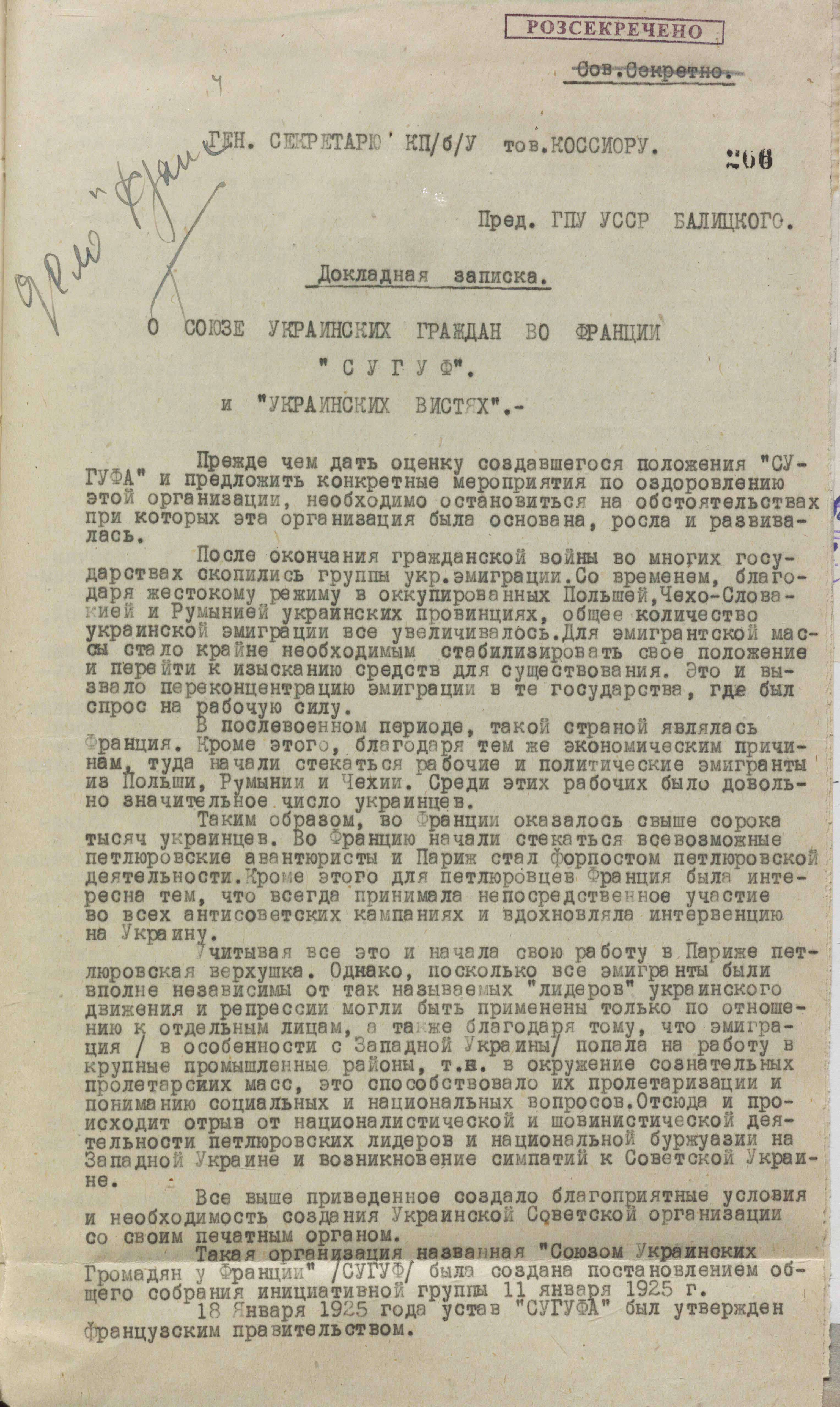

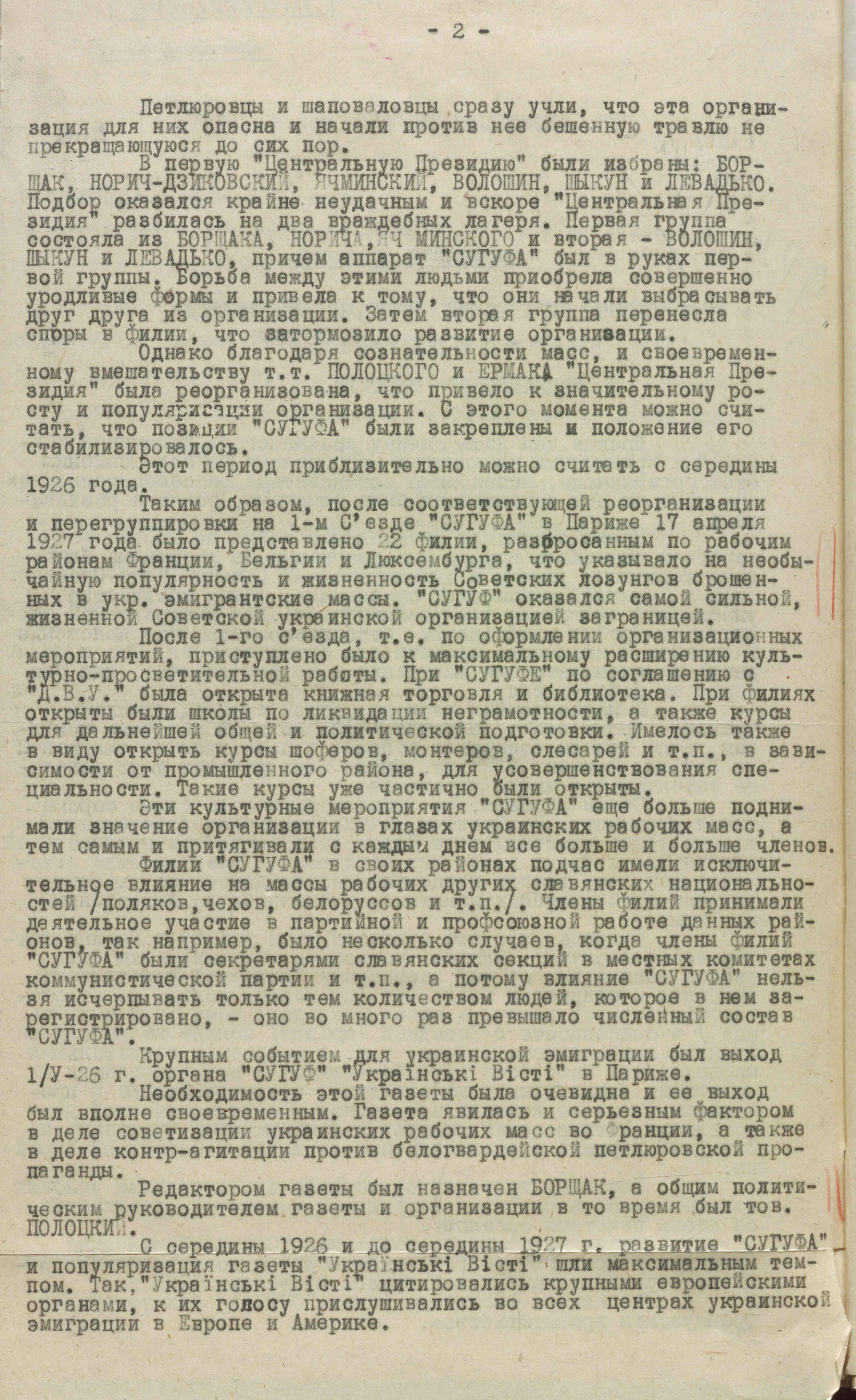

At the Head of the Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France

The archival funds of the Foreign Intelligence Service contain a memorandum from the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr Vsevolod Balytskyi to the Secretary General of the central committee of the communist party of Ukraine Stanislav Kosior “On the Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France “SUHUF” and “Ukrainski Visti”, dated May 1929. It outlines some of the circumstances and preconditions for the creation of the Organization. The point is that after the First World War, a large flow of emigrants, including those from Ukraine, went to France, where there was a demand for labor. This emigration was diverse. In Paris, former members of the Ukrainian People's Republic, who grouped around Symon Petliura and other leaders of the national liberation movement, were mostly concentrated. In large industrial regions there settled representatives of working professions who joined the local proletarian masses, among whom communist ideas were spreading.

“This is the origin,” the document points out, “of the departure from nationalist and chauvinistic activities professed by Petliura's leaders and the national bourgeoisie in western Ukraine, and the emergence of sympathy for soviet Ukraine. All of the above created favorable conditions and the need for the emergence of a Ukrainian soviet organization with its own printed organ. Such an organization, called the Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France (SUHUF), was created by a resolution of the general meeting of the initiative group on January 11, 1925” (FISU. – F.1. – Case 6738. – P. 266). According to the statute, the idea of SUHUF was to unite Ukrainians who recognized themselves as citizens of the Ukrainian ssr.

It is further noted that after interference of soviet representatives, the Central Presidium was reorganized, its branches appeared in Belgium and Luxembourg, and eventually SUHUF became the strongest soviet Ukrainian organization abroad. The Union gained even greater weight after the “Ukrainski Visti” newspaper began to be issued, edited by I. Borshchak. The document emphasized that the newspaper became a significant factor “in the cause of the sovietization of Ukrainian workers in France, as well as in countering Petliurists’ propaganda” and that it was quoted in both Europe and America. The pages of the newspaper openly proclaimed that “Ukrainski Visti” defended the United Ukrainian Soviet Republic on all Ukrainian ethnographic lands”. That is, the united Ukraine, but as part of the ussr.

The generalized information on I. Borshchak with reference to correspondence between the foreign department of the ogpu of the ussr and the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr for 1928-1929 states that his activity at that time “was to some extent instructed or controlled directly from Kharkiv, through our residentura in Paris. It is also known that Borshchak was paid 250 American dollars (the documents do not mention who and for what was payng him), his articles were published in Ukrainian newspapers (“Proletarska Pravda”, Kharkiv) and he was sent a fee ”(FISU. – F.1. – Case. 6738. – P. 85).

The archival documents also mention who funded the newspaper. In particular, the letter from moscow signed by the deputy chief of ogpu Abram Slutskyi to the chief of the foreign department of the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr Volodymyr Karelin, dated March 14, 1934, states that SUHUF “at our expense was publishing two newspapers in France – “Ukrainski Visti” (in Ukrainian) and “Junker Nouvelles”(in French)”. That is, at the expense of ogpu or in general, for soviet money. A copy of the document sent from the secretariat of the communist party of France to the secretariat of the communist (bolshevik) party of Ukraine was attached to the letter. But the attachment is missing. At the same time, the very mention of such exchange of information shows that both soviet special services and communist parties were integrated into this process.

On the pages of “Ukrainiski Visti” I. Borshchak actively opposed Simon Petliura and his policies. Not surprisingly, in 1926 he became the head of the Committee on the Organization of Defense of Samuel Schwartzbard – the killer of the Chief Otaman of the UPR. The case file mentions that under I. Borshchak’s instructions, a Lekash – Borshchak’s acquaintance travelled to Ukraine from France, who purposefully tried to collect information about the allegedly unlawful actions of the Petliurists in relation to the Jewish population. Quite possibly, all those measures were directed by the residentura of the ogpu.

On Contact in Sûreté Générale

Applying for soviet citizenship, I. Borshchak was not going to return to the ussr. Even in his application request, he pointed out: “Asking formally… to grant me soviet citizenship, I intend to continue to stay in France and fight with the pen and a word for the implementation of the above mentioned ideas”.

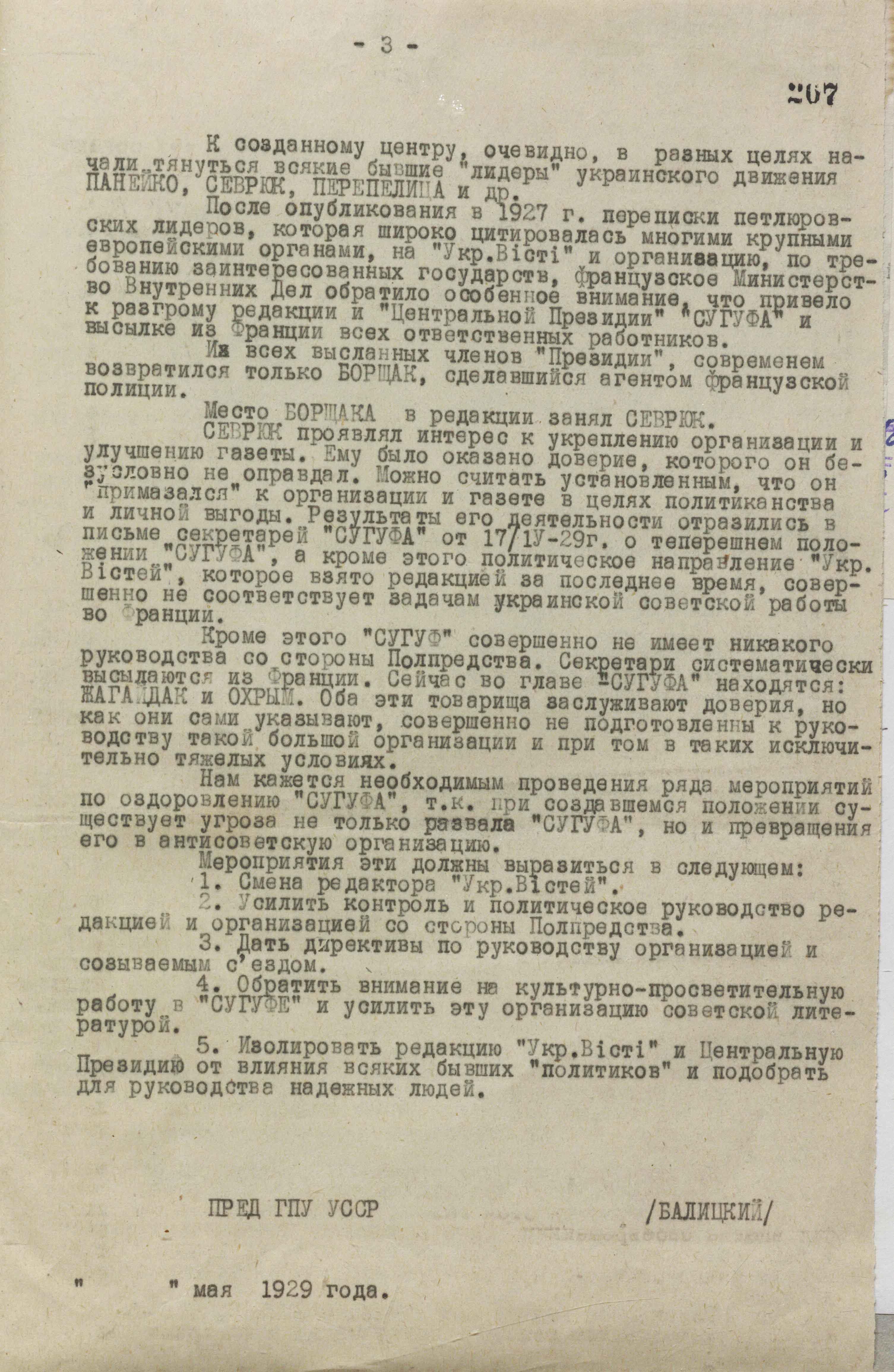

But things did not go as he and his curators had planned. In 1928, the government of France decided to deport the SUHUF leadership from France because of the latter’s open pro-soviet policy. So I. Borshchak found himself in Belgium. French historian Rene Marttel defended him and thanks to him I. Borshchak was allowed to return to Paris. But, as shown by archival documents, the ogpu residentura’s attitude to him was no longer the same as before.

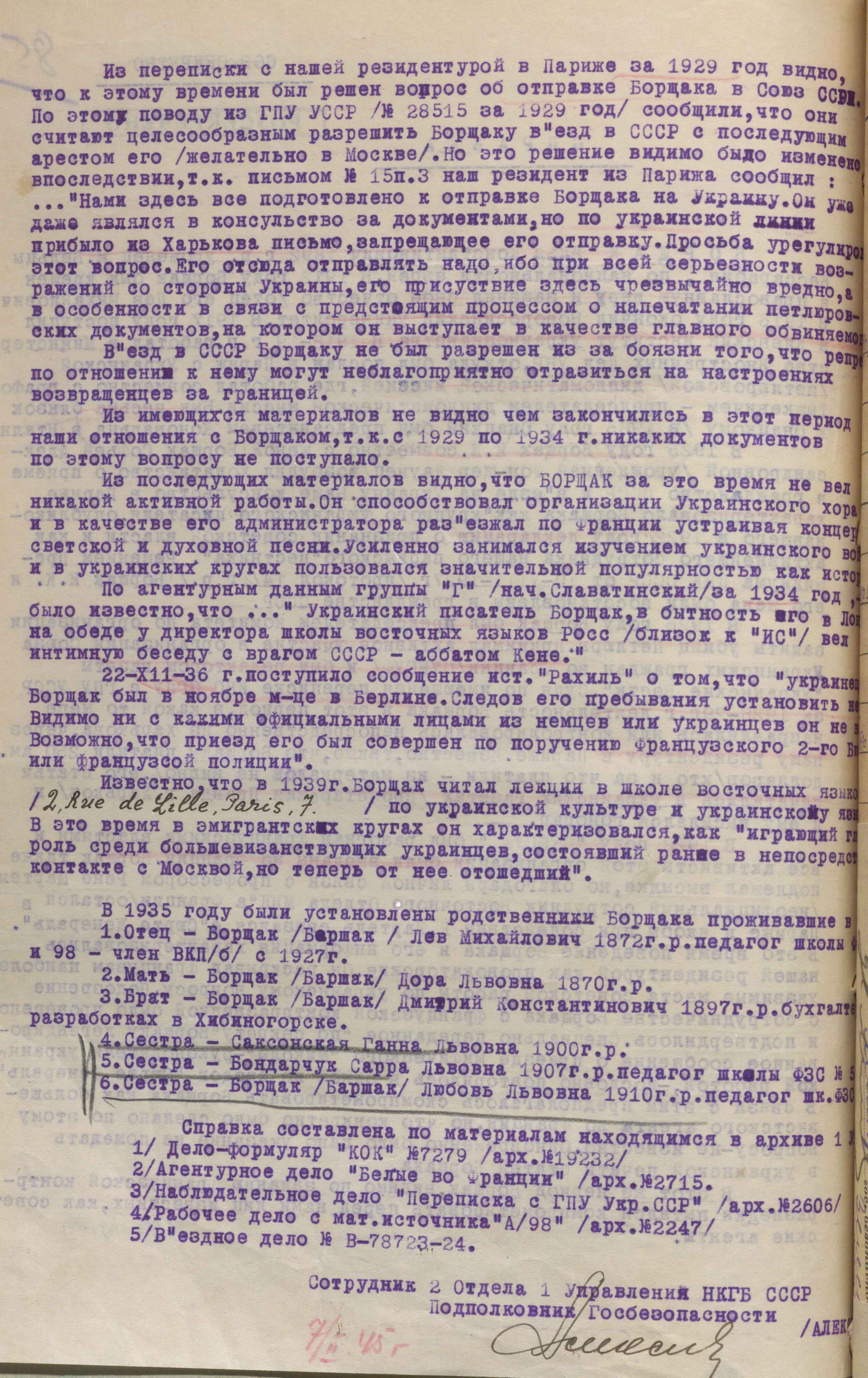

One of the documents reads as follows: “Thanks to his relations with Professor Rene Martel (related to Sûreté Générale), I. Borshchak managed to avoid eviction. According to our Paris residentura, Borshchak's behavior and information were provocative at that time. The checking revealed that I. K. Borshchak is connected with the French intelligence Sûreté Générale, which gave grounds to terminate all contacts with him” (FISU. – F.1. – Case. 6738. – P. 145-146).

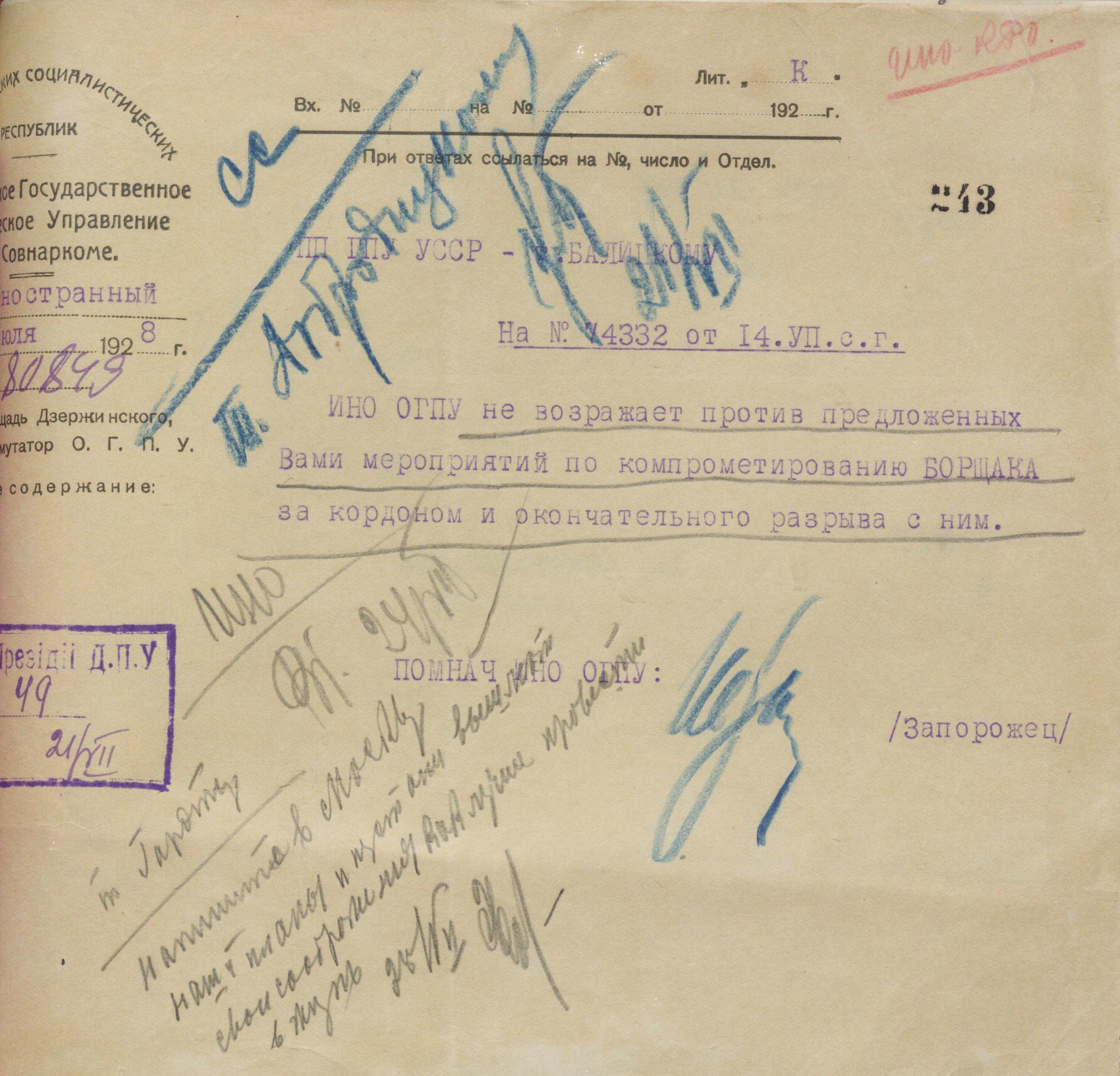

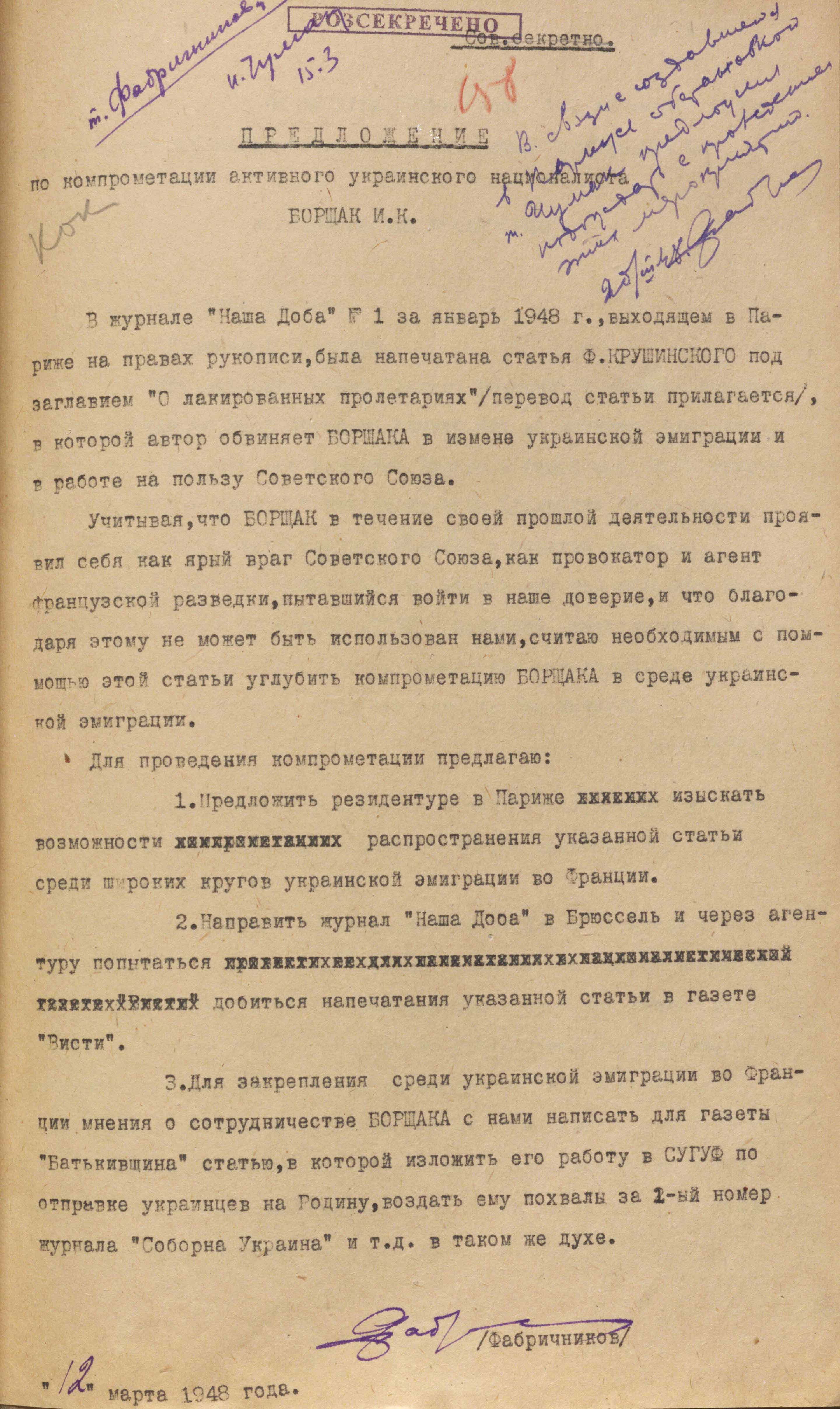

Information that I. Borshchak was involved in cooperation with French special services, in particular with political police, appears in many documents. Therefore, the soviet representative office removed him from editing “Ukrainski Visti”, and the Paris residentura started his operational cultivation. The correspondence between Kharkiv, moscow and Paris reguarding I. Borshchak’s further fate, lasted for several months. He was labeled an agent of Sûreté Générale. The decision on what to do with him was made in 1928. At that time, the following directive was sent from moscow to the chief of the ogpu of the Ukrainian ssr Vsevolod Balytskyi: “The foreign department of the ogpu has no objection to the measures you have proposed to compromise Borshchak abroad and finally break with him” (FISU – F.1. –Case 6738. – P. 60)

The gpu of the Ukrainian ssr soon reported on the fulfillment of the task: “...We have forbidden “Proletarska Pravda” to publish Borshchak’s articles, and now we will extend this ban to the entire Ukrainian press. We ask for urgent instructions on the following issues: sending letters to Borshchak that compromise him in the eyes of Sûreté Générale and publishing them in Ukrainian newspapers, as Borshchak, after learning that relations with him are finally being severed, may begin the “exposure” (FISU. – F.1. – Case 6738. – P. 73).

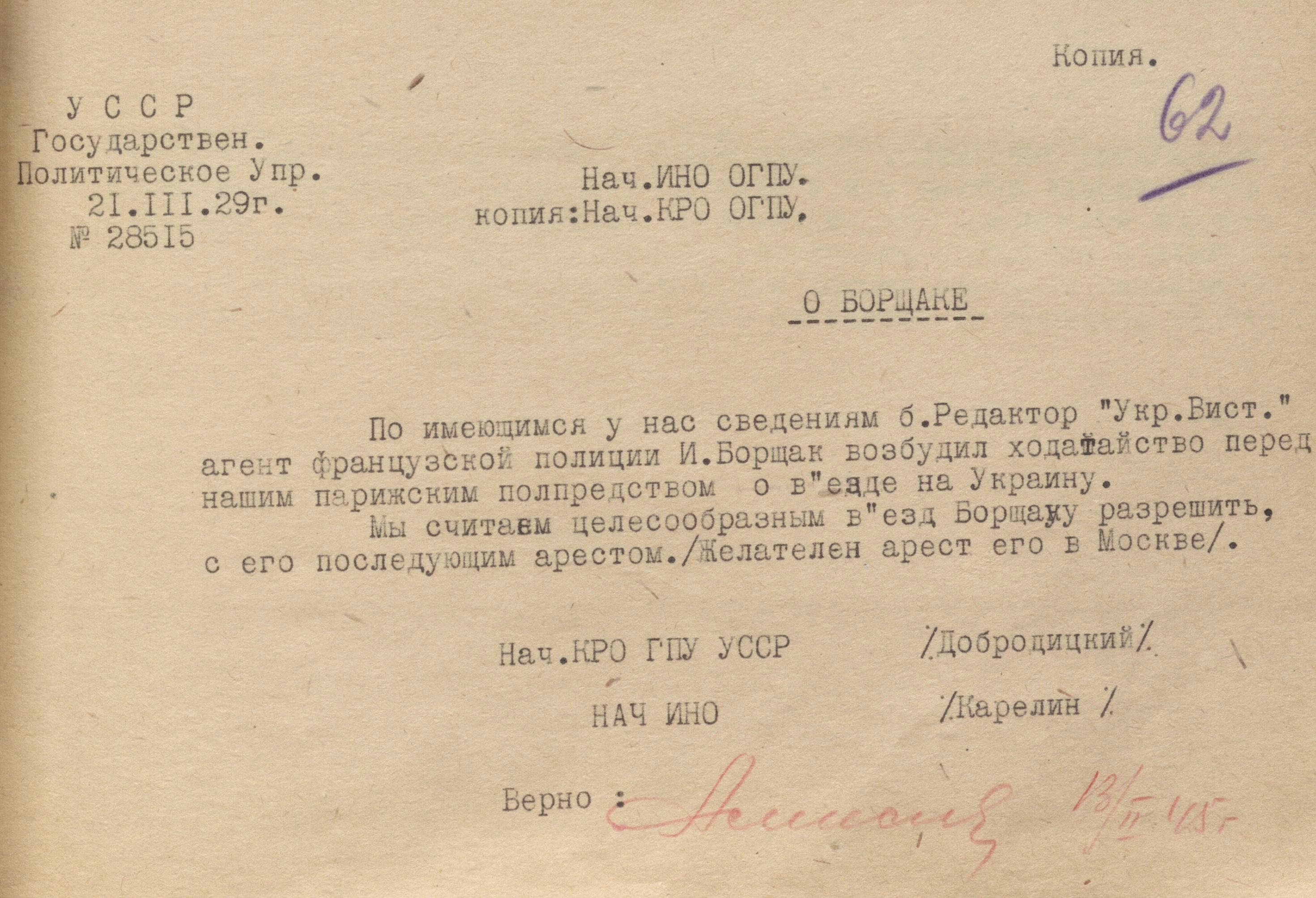

The papers, dated 1929, state that the ogpu was going to grant him permission to leave for the ussr and arrest him immediately upon his arrival in moscow. It went so far that the soviet consulate was already preparing the necessary documents for his departure. But an instruction came from the gpu of the Ukrainian ssr in Kharkiv, to suspend the process. Soon it was explained that I. Borshchak’s arrest and trial could negatively affect the mood of those Ukrainian emigrants whom the bolsheviks strongly urged to return to their homeland, where they were actually caught by stalin's secret services as unreliable or even foreign spies.

In the 1930s, the chekists lost sight of I. Borshchak for a period of time. Then his wife died, and he somewhat retreated from political activity. Instead, according to one of the intelligence reports, he created a choir with which he traveled around France for three years giving concerts in Catholic churches. In addition, he focused on promoting Ukrainian culture in France and became the founder of the Ukrainian Studies Department at the National School of Living Oriental Languages in Paris.

Unable to directly monitor I. Borshchak's activities, the gpu began operational cultivation of his close relatives who lived in the ussr. In 1935, they tracked down I. Borshchak's father Lev Mykhailovych in Odesa and summoned him for a conversation, during which they thoroughly questioned him about his sons. In 1937, during a second summons for interrogation, the father had a heart attack, which led to his death. I. Borshchak’s brother Dmytro was sentenced to a long term in prison on trumped-up charges. He was sent to the GULAG, where he died. One of the sisters was also sentenced to two years in labor camps.

Archival documents say nothing about I. Borshchak’s attitude to those events. On the other hand, the repression of his close relatives did not make him an implacable critic of the soviet regime. Moreover, his opinion about Ukraine’s place in the world order did not change. A report dated 1950 states that after the liberation of France from the Nazis, he published an article in a Parisian newspaper in which he defended the idea that Ukraine could never have been united had it not been for the ussr. He stated that he was in favor of the Ukrainian soviet republic, but for the one that existed during the heyday of Ukrainization.

No information was found in the archival documents about his second attempt at that time to obtain permission to return to the ussr. He allegedly had already received a passport and was preparing to travel, but at the last minute changed his mind, – as stated by open sources, under the influence of information about the miserable life in the ussr and the resumption of repression. One of the reports from the Paris residentura only mentions his visit to the soviet consulate in 1947 without specifying the purpose.

In general, as shown by the documents, the bolshevik regime needed I. Borshchak only when he clearly fit into the scheme of soviet special propaganda abroad. At that time, he was provided with all possible support in leading the Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France, editing the newspaper “Ukrainiski Visti”, publishing articles in newspapers and magazines in the ussr, and was paid for his services. When the chekists realized that he was playing a double game, they tried to compromise him in emigrant circles as a bolshevik agent. No past services to the soviet government were taken into account. This was done to everyone. They treated everyone as a waste material with which they could do anything. When someone retired, changed one’s views and beliefs, or refused to cooperate, someone else was found to replace him/her.

By the decision of the board of the ussr kgb of July 31, 1959, tThe operational case against I. Borshchak was left in progress for some time. Although he was seriously ill at the time, he was struck by paralysis and lost his speech. So, he was no longer a person who needed to be neutralized at all costs. But they still tried to collect information about him to the last days of his life. They pointed out that there were not enough agent capabilities in his immediate environment for active cultivation.

Ilko Borshchak died on October 11, 1959. He left behind many mysteries which researchers of his work and scientific activities are still trying to solve.