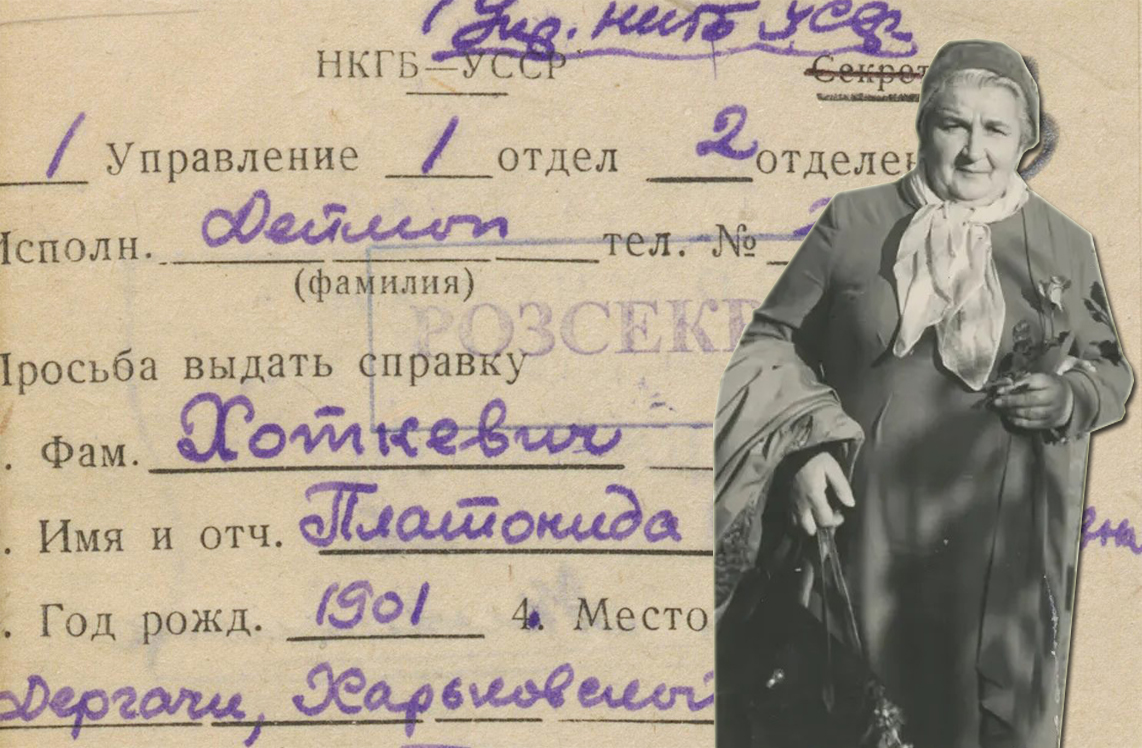

Platonida Khotkevych. “So That She Would Not Publish Anything About Her Husband”

12/31/2024

In the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine, a thin file was found on Platonida Khotkevych, the wife of a prominent Ukrainian writer, literary critic, art historian, bandura player, composer, historian, ethnographer, and theater figure Hnat Khotkevych (born December 31, 1877), who was repressed by the stalinist regime and shot dead on October 8, 1938, for “participating in counterrevolutionary activities and spying for Germany”. His wife was tracked down by smersh (The name смерш (smersh) was coined by joseph stalin as a shortening of the russian-language phrase cмерть шпионам (smertʹ shpionam, "death to spies"- Transl.) in Prague after World War II and arrested “so that she would not publish anything about her husband”.

The case allows us to learn only fragmentarily about where Hnat Khotkevych's wife was and what she did during the war, how she ended up abroad, and why she became subject to stalin's secret services’ special attention. At the same time, her story is yet another testament to the horrific practice of the postwar punitive system, when people who were listed as so-called enemies of the soviet power, counterrevolutionary elements, Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists, or even those who simply did not want to return to their homeland for fear of reprisals were tracked down, arrested, or even kidnapped in the soviet occupation zone and even beyond.

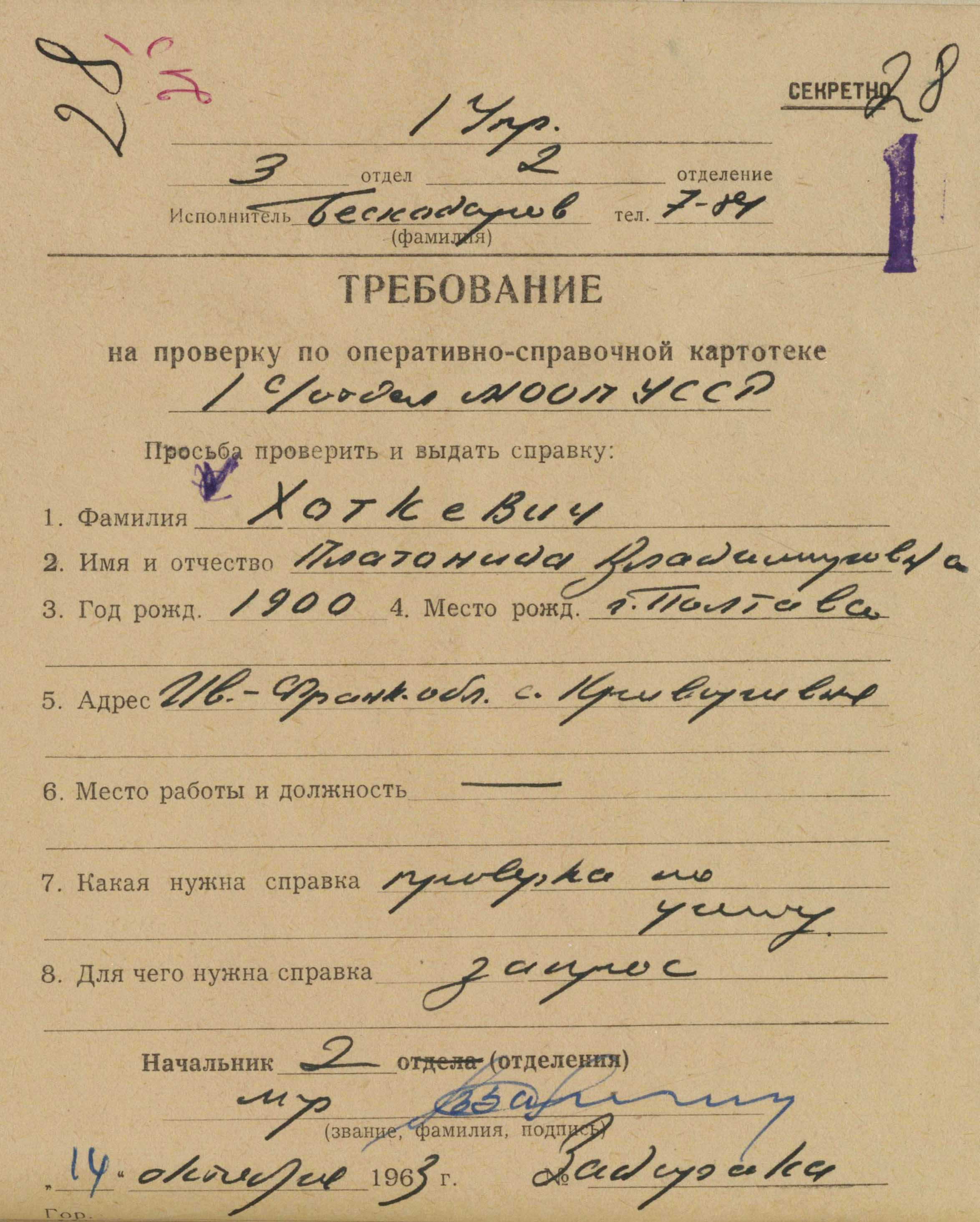

One of those numerous lists is mentioned in the case file. It is an excerpt from agent “Boris”’ report dated December 9, 1944. In it, the nkvd agent named and characterized those who remained in the territory occupied by Nazi troops. He referred to them as “traitors and Ukrainian nationalists”. The total number of people on the list is unknown. Platonida Khotkevych is listed as the 34th person. The following is pointed out about her:

“...a resident of Kharkiv, the wife of a well-known Ukrainian nationalist convicted of political crimes against the soviet power Hnat Khotkevych. A teacher by profession.

In Lviv, she worked in the social security department of the UCC [Ukrainian Central Committee], where she was very active in the resettlement of families of Ukrainians fleeing the eastern regions. The UCC leaders absolutely trusted her... A committed nationalist, she was evacuated from Lviv to Krynica, Muszyna, Nowy Sącz...”(BSA of FISU. - F.1. – Case 7198. - Vol. 2. - P. 3).

The people's commissar for state security of the Ukrainian ssr Serhiy Savchenko made a rather eloquent resolution on the agent’s report. In it, he set the task to take a form-based record of all those who fled abroad and begin to cultivate them, to collect information on each person and their close relatives who remained in the ussr. It was also necessary to check who of the fugitives was a member of the agent apparatus, and, depending on the information collected, to establish contact with them for further use, and in case of refusal, to liquidate them.

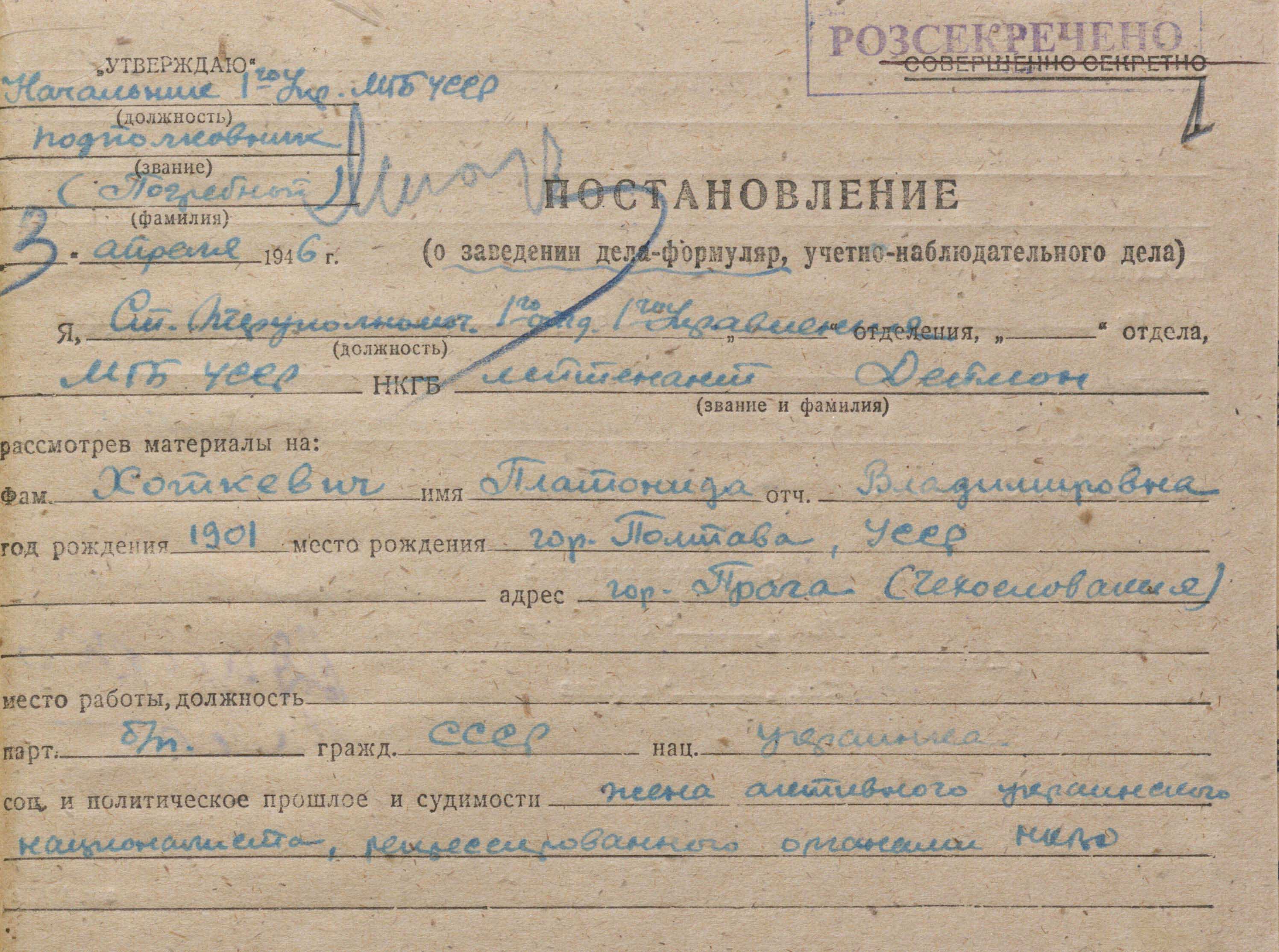

Then the repressive machine began to gain momentum. As such lists were numerous, the chekists did not get round to each person immediately. The case against P. Khotkevych was opened in June 1945. The decision stated that she was the wife of a repressed Ukrainian nationalist. There is no information about him in the case file. But at least the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr had some general information about him, otherwise they would not have shown such interest in his wife.

In the interwar period, Hnat Khotkevych was a fairly well-known figure in the literary and artistic community. He was a Ukrainian theater and socio-political activist, composer, writer, translator, bandura player, violinist, pianist, singer, screenwriter, playwright, historian, art critic, ethnographer, teacher…

In the 1920s – 1930s, a collection of his works was published in eight volumes. The most significant achievement of his prose work was the romantic story from Hutsuls’ life, “The Stone Soul”. He studied and popularized the works of Hryhoriy Skovoroda, Taras Shevchenko, Yuriy Fedkovych, and Olha Kobylianska. He translated a lot from world classics – Shakespeare, Moliere, Schiller, Hugo. He was the founder, organizer, and director of student, village, and workers' theaters. He wrote dramatic works for them, some of which were not very favorably received by the authorities of the time. In particular, in the tetralogy “Bohdan Khmelnytskyi”, he condemned the Pereyaslav Agreement as an act that led to the enslavement of Ukraine by russia.

Besides, Hnat Khotkevych created a kind of Kharkiv school of bandura playing, published the first textbook of bandura playing, taught a bandura class at the Kharkiv Music and Drama Institute, and led the Poltava Bandura Chapel, for which he created a respectable repertoire. In total, he composed about 600 pieces of music, including romances, choruses, string quartets, and large-format works for the bandura and a bandura orchestra.

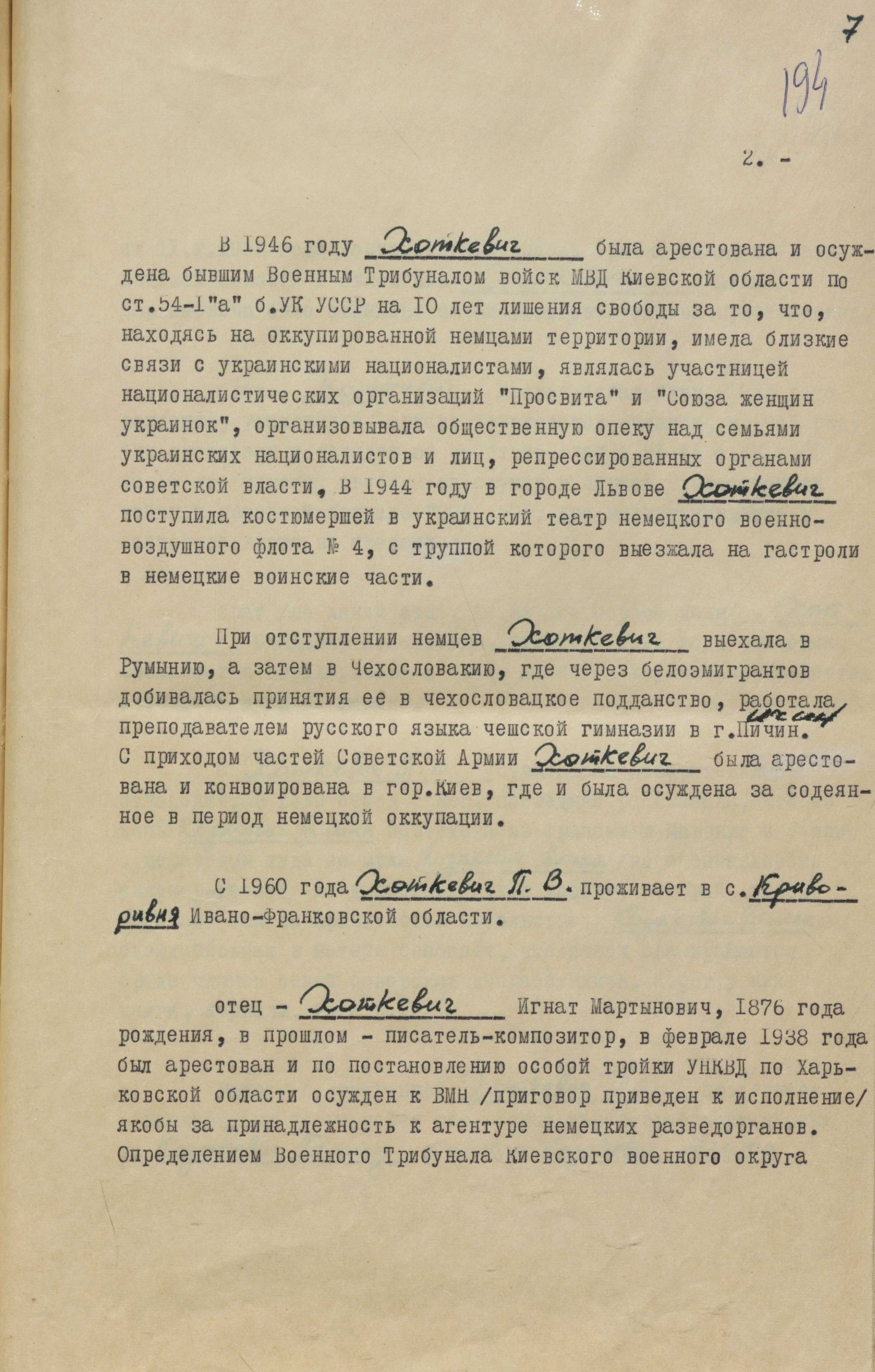

He was arrested on February 21, 1938, on suspicion of participating in an “anti-soviet Ukrainian nationalist terrorist organization”. During interrogations, nkvd investigators beat a confession out of him that he became a nationalist after moving to Halychyna in 1906 and meeting Olha Kobylianska, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Kyrylo Studynskyi, Filaret Kolesa, Mykhailo Rudnytskyi, and Oleksandr Barvinskyi. Allegedly under their influence, in 1913 he returned to russia as an ardent nationalist. Under pressure, he “admitted” that he had recruited a number of figures for espionage activities who provided valuable economic, technical, and military information. He allegedly passed all this information to German intelligence through his teacher of the German language. Therefore, he groundlessly pleaded guilty to espionage for Germany and to participating in a “Ukrainian nationalist insurgent organization”.

On September 29, 1938, the “special troika” sentenced Hnat Khotkevych to death by firing squad with confiscation of property. On October 8, 1938, he was executed in the basement of the Kharkiv internal prison of the nkvd. His wife Platonida Volodymyrivna (the artist's third wife) remained at large with their two children, a son Bohdan and a daughter Halyna. She knew nothing about her husband's fate and for a long time did not know if he was alive at all.

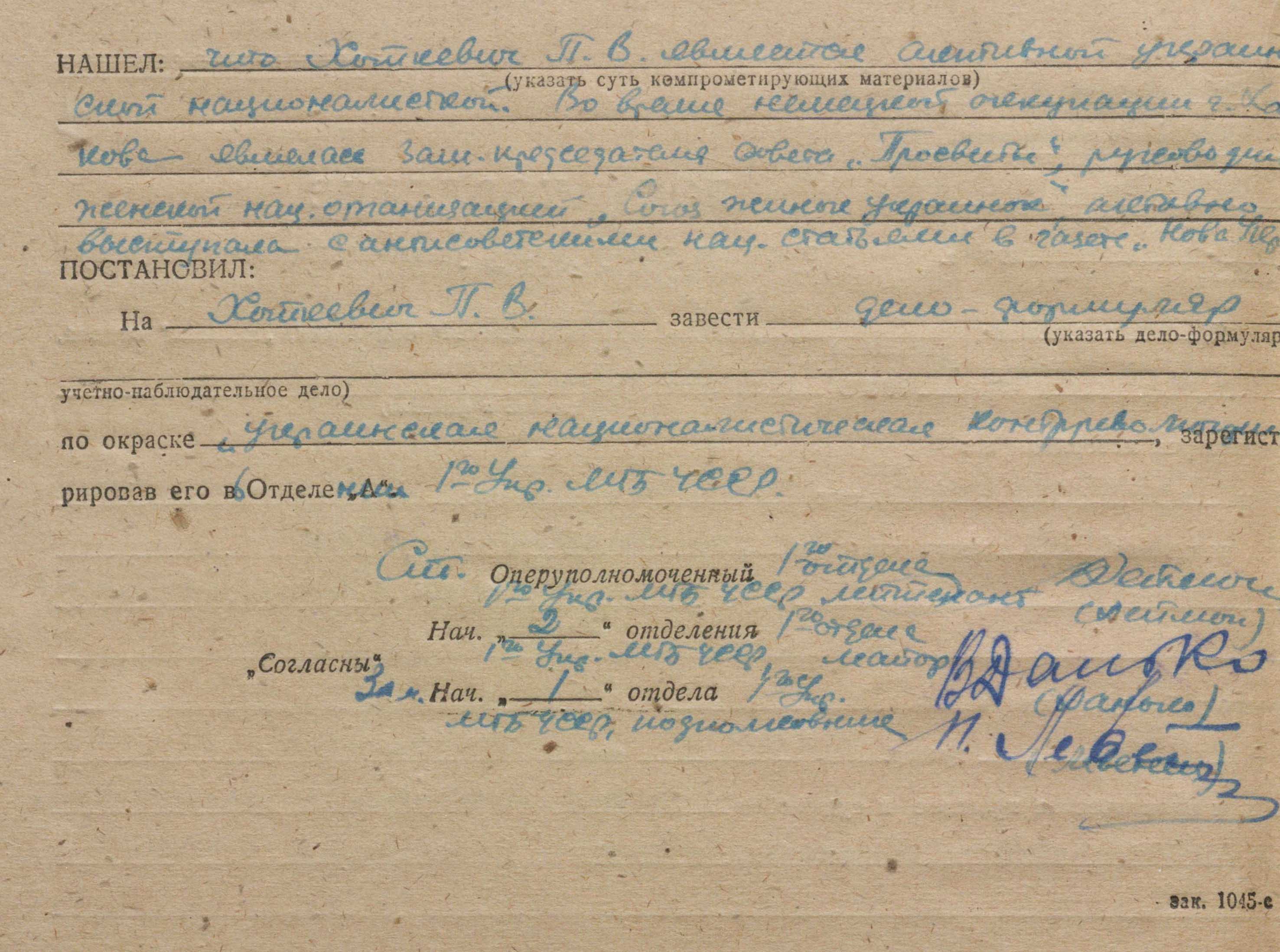

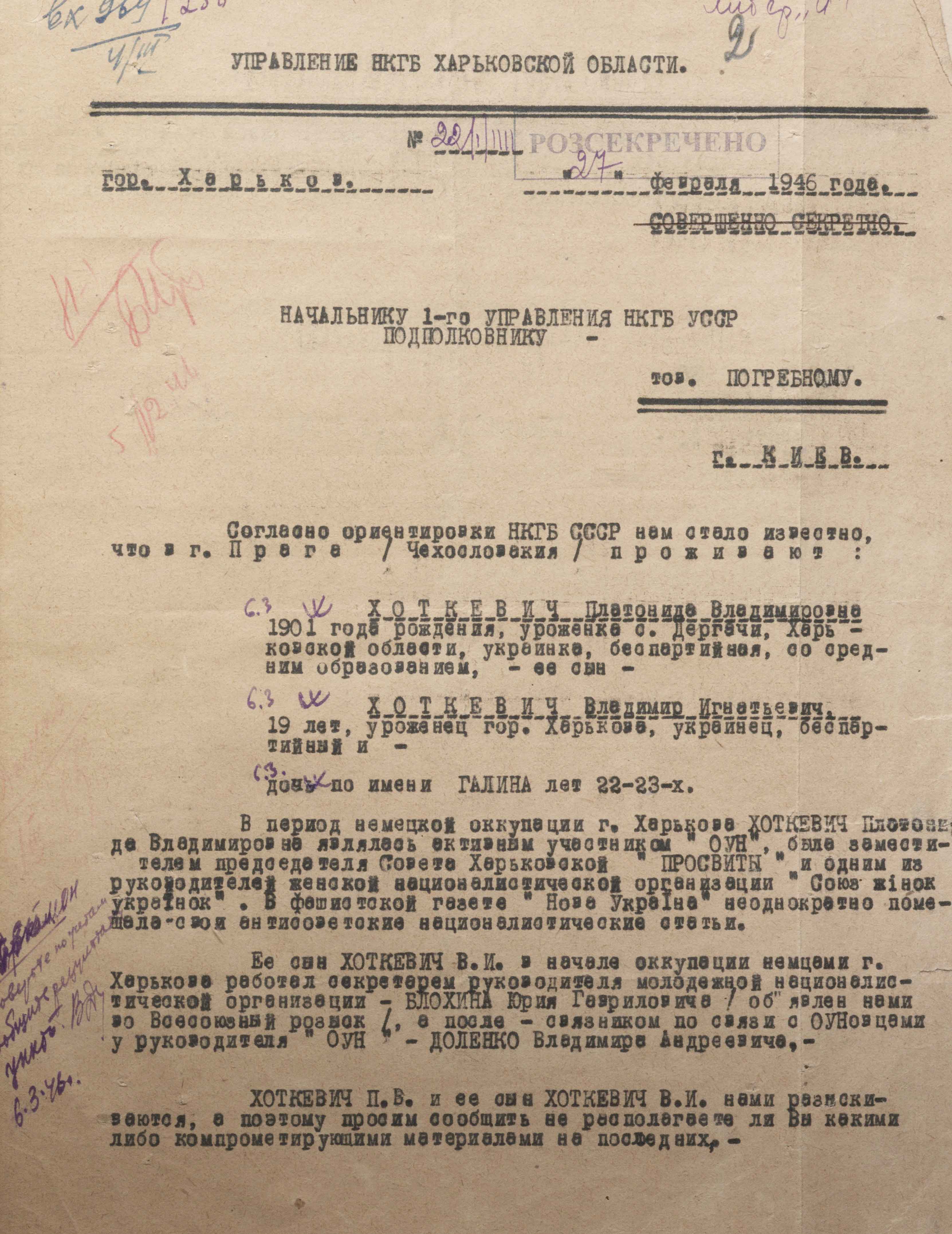

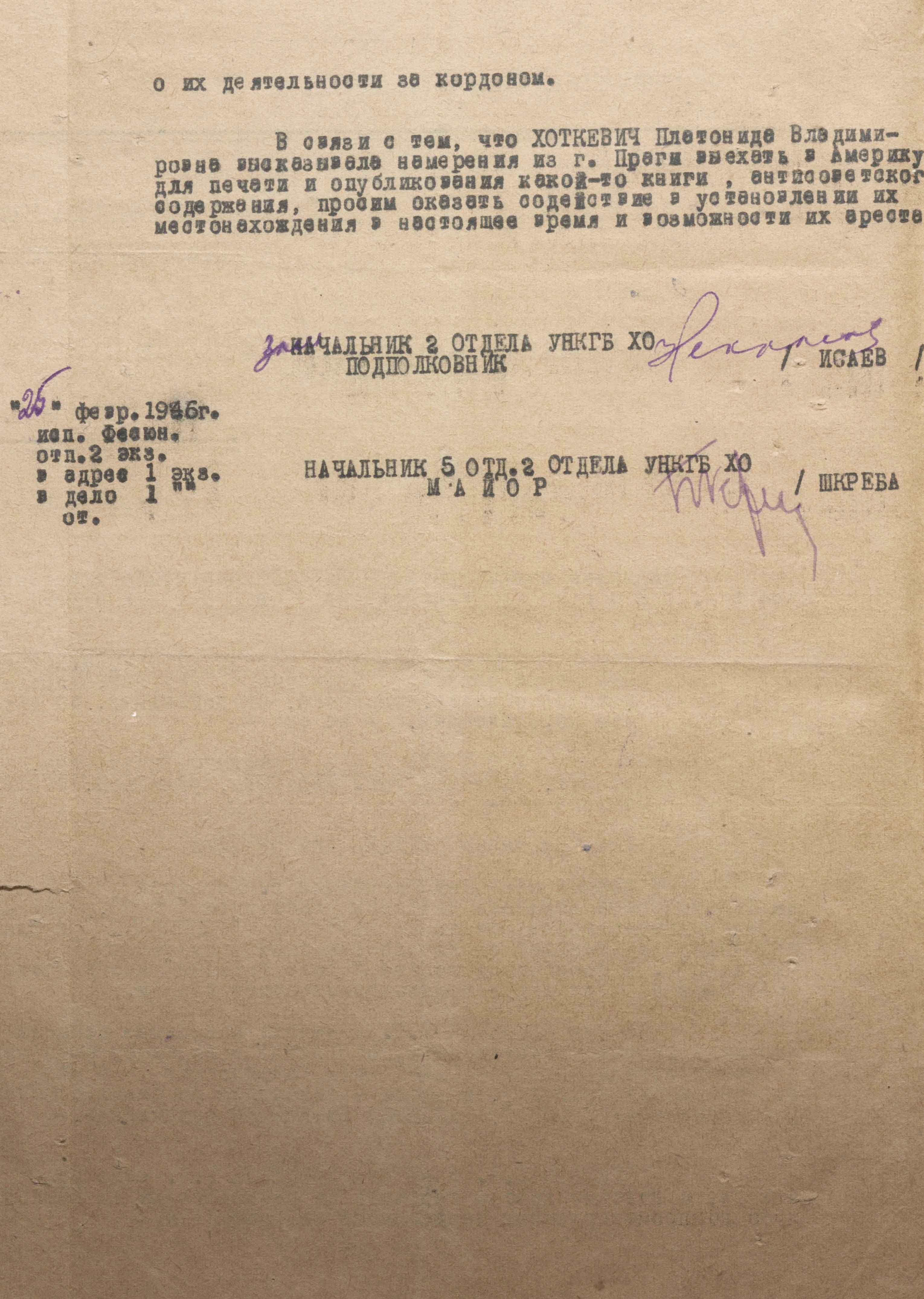

At the beginning of the German-soviet war, Platonida lived in Kharkiv. In order to survive in the occupied city, she got a job as a librarian at the city government. In addition, as noted in a brief dossier compiled by the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr, “she was deputy chair of the board of the “Prosvita” society, headed the “Union of Ukrainian Women”, a women's nationalist organization in Kharkiv, and actively wrote anti-soviet nationalist articles in the “Nova Ukraina” newspaper. Khotkevych, along with her daughter Halyna, born in 1929, and son Bohdan, born in 1925, fled Kharkiv with the Germans. Her son Bohdan was the secretary of the Kharkiv Youth Ukrainian Nationalist Organization... Khotkevych spoke of her intentions to leave for America to have her anti-soviet book published” (BSA of FISU. - F.1. - Case 7198. - Vol.1. - P.17).

Having received this information, the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr put P. Khotkevych on the all-ussr wanted list. Shortly after, in March 1946, the mgb received a report from the smersh counterintelligence department of the central group of the ussr troops in Europe that P. Khotkevych had been found in Prague and detained some time later. During her first interrogations, she told them that she had moved from Kharkiv to Lviv. There, in February 1944, she got a job as a costume designer at the Ukrainian Travelling Theater, with which she toured Poland and Romania. In February 1945, she found herself in Prague, where she was sheltered in the family of Professor Dmytro Antonovych, the former Director of the Ukrainian National Museum in Czechoslovakia and Hnat Khotkevych's friend since their student days.

“In Prague”, the report states, “Khotkevych stayed in touch with her friend Yurii Diachuk, who was arrested by the Czechoslovak state security authorities as a nationalist contact agent with the counterrevolutionary organizations of the OUN and UHVR in Munich” (BSA of FISU. - F. 1. - Case 7198. - Vol. 1. - P. 16).

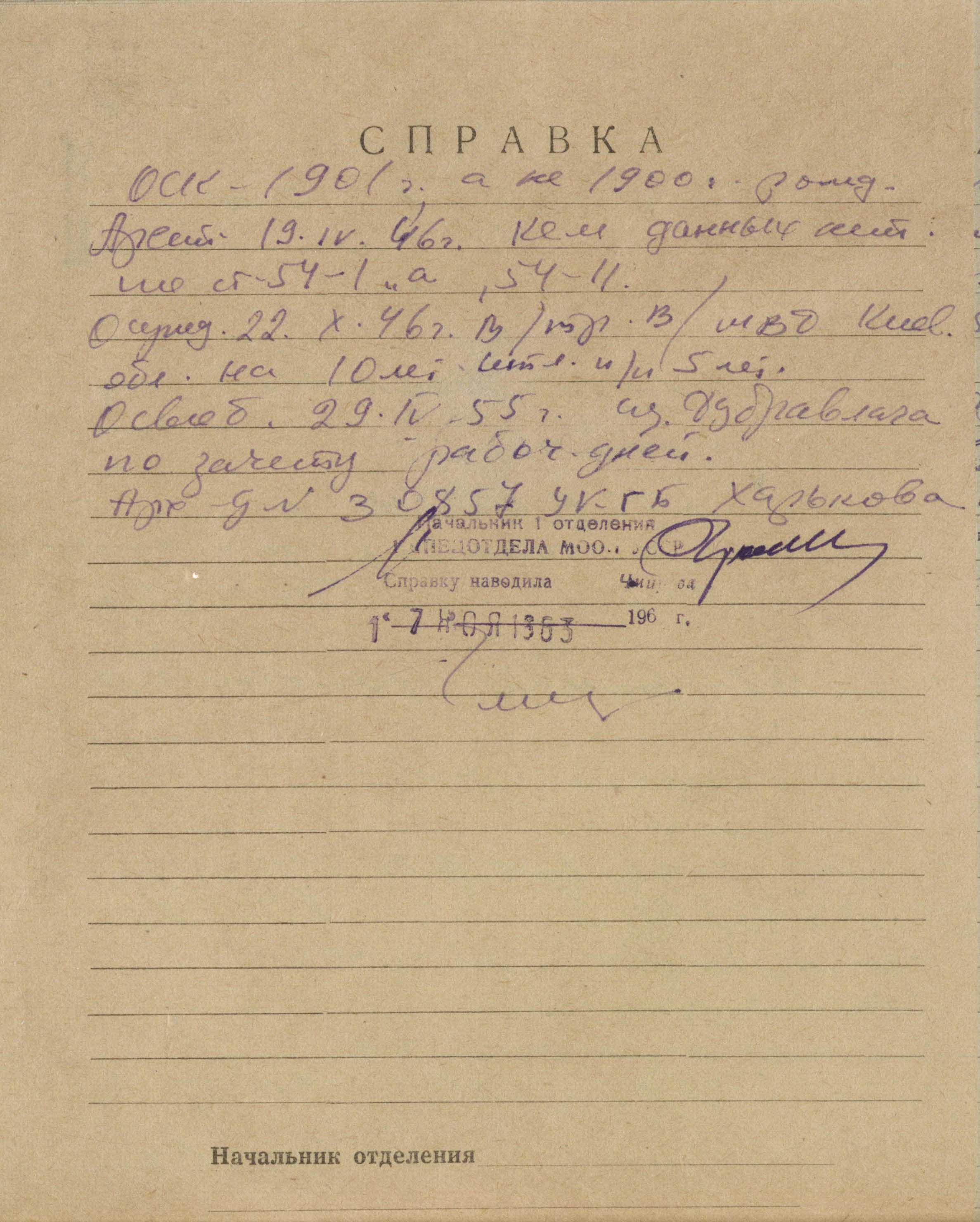

This information further interested the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr, which requested that P. Khotkevych be escorted to Kyiv for investigative purposes. There is no information in the documents from the archival funds of the Intelligence Service about how the investigation was carried out. However, it is known that it was short. There is an extract from the list of persons detained at that time by the smersh abroad and taken to the investigative unit of the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr. Platonida Khotkevych is listed as the 36th person. It is reported that she was arrested on April 20, 1946, by the smersh central department in Jičín (Czechoslovakia), and on April 22, 1946, she was sentenced to 10 years in labor camps with a 5-year suspension of rights and confiscation of property.

The story of her children was no less dramatic. According to archival documents, her son Bohdan ended up in the American occupation zone after the war, was handed over to the smersh in May 1946, and on September 23 of that year was sentenced to 10 years in labor camps by a military tribunal of troops of the ministry of internal affairs of Kyiv region. The mgb received more information about Khotkevych’s daughter Halyna. It was reported that in 1944 she was studying in Lviv in the 5th form of a secondary school and at the same time at the children's music conservatory. At the time when Platonida went to Romania with the theater and then ended up in Czechoslovakia, Halyna allegedly went to Hungary with the pianist she was taught by, and from there to Germany. She soon moved to France, where the teacher had relatives. Her mother knew nothing about her daughter's ordeal, and their communication was cut off.

According to open sources, Platonida Khotkevych served her exile in camps in sverdlovsk and kirov regions and in karaganda. She was released in February 1956. At the same time, she finally received an answer from the kgb about her husband, who allegedly died of a stroke in prison on October 13, 1942. But it was not true. Prior to that, she had repeatedly written letters to lavrentiy beria and Nikita Khrushchev asking for information about Hnat’s fate, appealed for help to Ukrainian writers Mykola Bazhan and Oleksandr Korniichuk, persuading them that her husband was innocent, but to no avail.

Having returned from exile, Platonida found herself homeless. The house that belonged to her husband during his lifetime in the village of Vysoke, near Kharkiv, was not returned to her. So she went to Lviv. Friends helped her get a job with the Carpathian Geological Expedition. That's how she ended up in the mountainous, picturesque village of Kryvorivnia in Stanislav (now Ivano-Frankivsk) region. Ivan Franko lived in that village every summer from 1900 to 1914, and Hnat Khotkevych lived there from 1906 to 1912. In 1961-1966, Platonida was a librarian and Director of the Ivan Franko Museum in Kryvorivnia.

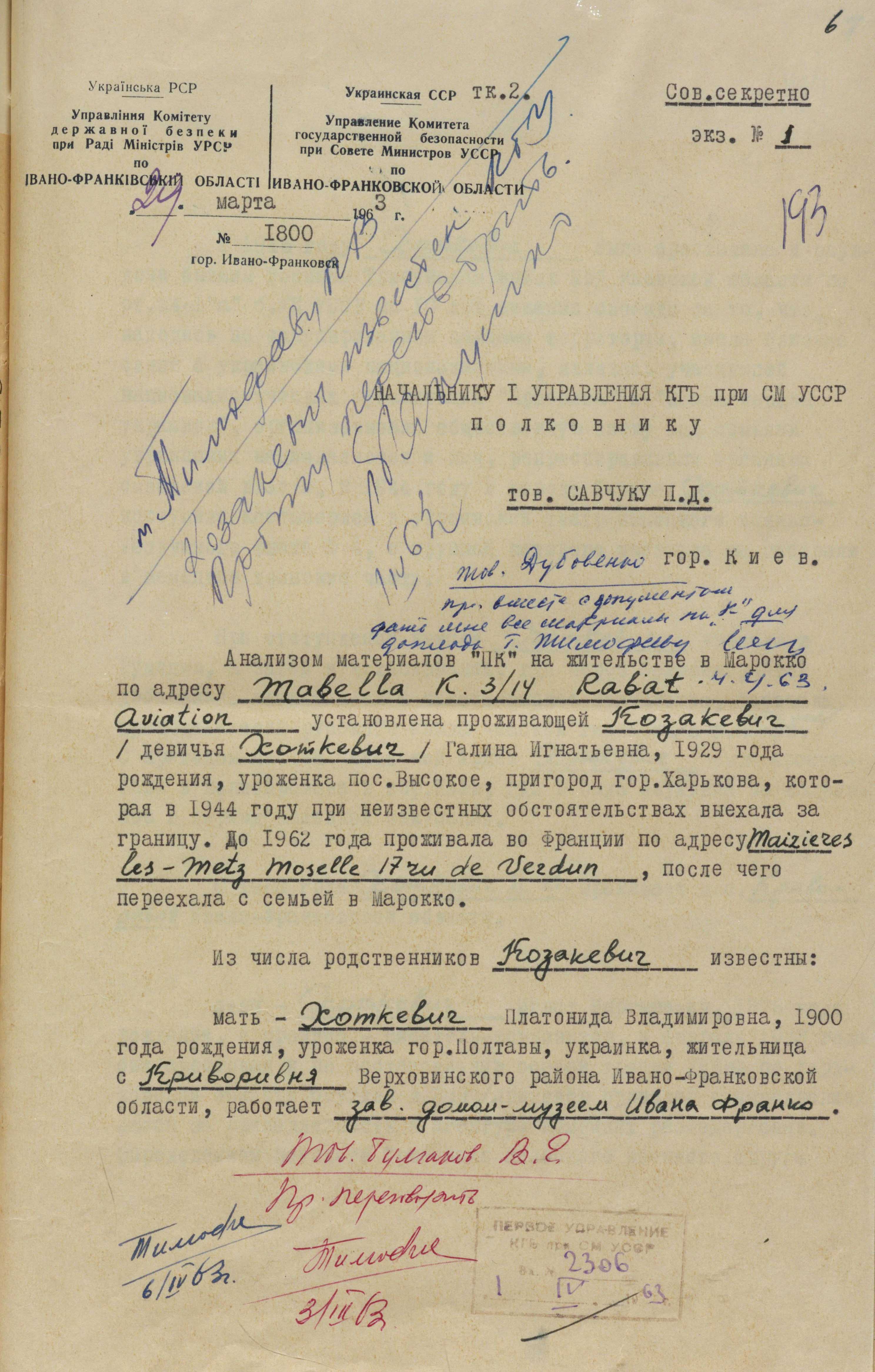

According to archival documents, at that time the Museum was visited by an officer of the local kgb department who introduced himself as an employee of some other state institution from the district center. But his interest was not ethnographic. The kgb learned that Platonida's daughter Halyna had been found abroad. Here is how this is described in one of the documents: “Until 1956, Khotkevych knew nothing about her daughter. In 1956, an article about the rehabilitation of H. M. Khotkevych was published in Issue 38 of the “Literary Newspaper”. Halyna read the newspaper and then wrote a letter to the Writers' Union in Kyiv asking them to tell her where her mother, P. V. Khotkevych, lived. This is how the connection between them was established” (BSA of FISU. - F. 1. - Case. 11263. - P. 204).

The document also reads that in France, Halyna married a student of the geology faculty whose father was a Ukrainian, a former professor at Kharkiv University. This information was gleaned from the correspondence between mother and daughter, which the kgb put under control. From the letters, they learned that Halyna's husband had become a certified geological engineer and was sent to work in Morocco in the French mission, allegedly at the Embassy. In addition, the kgb residentura in France was involved in collecting information. They showed interest in Halyna's husband with the intention of possible recruitment. They wanted to use Platonida in the future. They planned to talk her into inviting her daughter, son-in-law, and their children to the ussr, in order to carry out their plans on their territory. Given that Ivano-Frankivsk region was closed to foreigners, the kgb even sent a request to moscow to somehow resolve this issue. Other measures were also being developed.

However, according to archival documents, nothing came of it. In April 1965, Kyiv received a response from the first main directorate (foreign intelligence) of the kgb of the ussr. It stated that the subject of the cultivation was not of operational interest because he was not working at the embassy but was managing a geological laboratory in one of the ministries. Besides, they found out that he was not very favorably disposed towards the ussr. “In view of this, we are not interested in his visit to the soviet union”, the document stated.

Halyna Khotkevych's plans to visit her homeland did not work out either. Her dream came true only in the early 1990s. On her initiative, the former house of Hnat Khotkevych in the village of Vysoke, which was confiscated in 1938, was returned and became the museum named after him, the International Competition of Performers on Ukrainian Folk Instruments was launched in Kharkiv, and the Hnat Khotkevych Foundation for National and Cultural Initiatives was founded. Halyna also initiated the publication of her father's works, which were banned during the soviet era.

Having retired, Platonida Khotkevych lived in Ivano-Frankivsk, where she died in 1976. Halyna died in 2010 in Grenoble, France. Before her death, she bequeathed her collection of Easter eggs to be brought to Ukraine, to her father's house-museum in Kharkiv region. In France, Halyna not only had been creating Easter eggs for many years, but had been popularizing them through exhibitions and publication of postcards with their images.

In general, her life's work had been to preserve her father's good name and creative heritage, to restore the repressed memory of the Kharkiv kobza playing school, and to inform the diaspora and fellow Ukrainians about all that Hnat Khotkevych did not manage to do. She wrote a book of memoirs about her own family entitled “Where the Grass Does Not Prick”. In doing so, she also accomplished what the chekists once prevented her mother from doing, namely, conveying through the written word the truth about Hnat Khotkevych’s dramatic and tragic fate.