Solovki’s Escapees- In the UPR Intelligence Service

11/26/2021

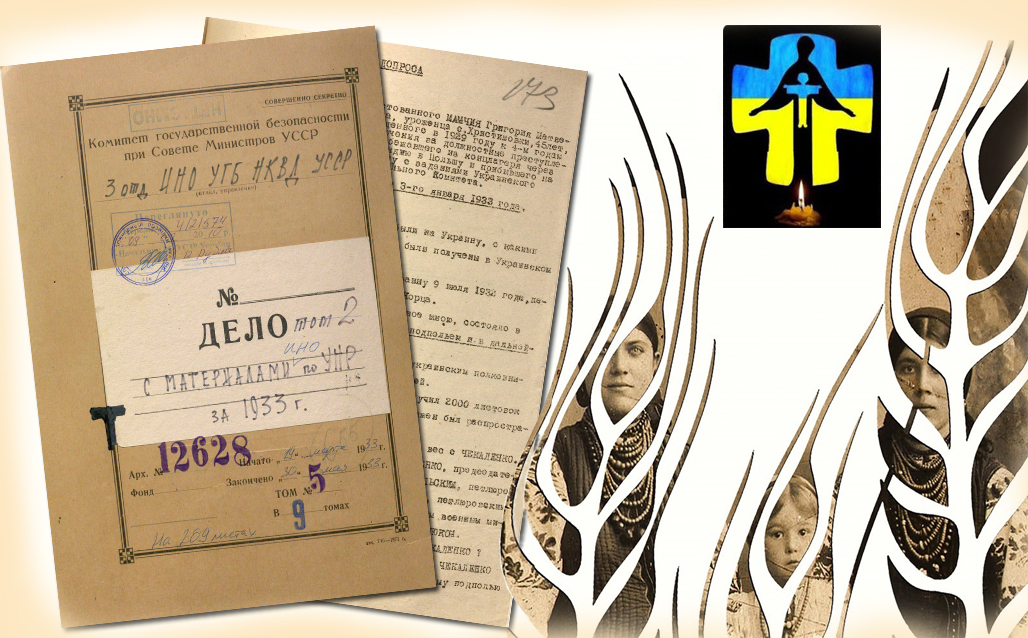

The archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine contain a number of documents dated 1932–1933 about how the UPR intelligence tried to obtain information about the real state of affairs in Ukraine at that time, including the terrible famine that befell the Ukrainian villages. One of the episodes of that epic is mentioned in the testimony of Hryhoriy Mamchiy, an escapee from the Solovki camp who, on the instructions of Vsevolod Zmienko, the head of the UPR's secret service, crossed the Polish-Ukrainian border to find out the situation in his native Cherkasy region, to establish contacts with locals who had a negative attitude to the Soviet authorities, and to try to organize resistance.

From archival documents we learn about the dramatic fate of Mamchiy Hryhoriy Matviyovych - “a native of the village of Khrystynivka, 45, in 1929 sentenced to four years in prison for official crimes, who escaped from a concentration camp through Finland to Poland and arrived in Ukraine on behalf of the Ukrainian Central Committee”. This is information from the protocol of interrogation in the GPU of the USSR of January 3, 1933.

According to G. Mamchiy, in October 1930 in Finland, where he had arrived from Solovki, he found the address of the Ukrainian community in France in one of the newspapers and wrote a letter to its leader Mykola Shapoval. In the letter he asked that he and his acquaintances, with whom he had escaped from the camp, be helped to move to France. Two months later, the answer came. But not from Mykola Shapoval, but from Levko Chykalenko from Warsaw, who actively cooperated with the emigration government of the Ukrainian People's Republic. He reported that he was taking care of escapees from the Solovki camp. So he congratulated Mamchiy on his successful escape and asked to write about his needy life in the concentration camp. Soon a letter arrived from the Minister of Military Affairs of the State Center of the Ukrainian People's Republic in exile, Volodymyr Salsky. He also congratulated on the escape and expressed hope to see the brave in the ranks of the UPR army.

The correspondence lasted almost a year. In September 1931, Hryhoriy Mamchiy, Semen Surzhko and Petro Obushnyi received permission to enter Poland for a period of three months. There they were gladly met and settled in an apartment. For several days, they were met by Vasyl Nedaykasha, the head of intelligence of the UPR special service, Roman Smal-Stotskyi, the Minister of Internal Affairs of the government in exile, Volodymyr Salskyi, the Minister of Military Affairs, and Yevhen Malanyuk, a writer and publicist.

During those meetings, they mostly talked about their stay in Solovki, about escape, about life in Ukraine and further plans. At this, according to archival documents, P. Obushnyi expressed a wish to stay on Polish territory, where he allegedly had relatives, and H. Mamchiy and S. Surzhko volunteered to be sent to the territory of Ukraine to conduct underground work.

During that period, it became increasingly difficult for the UPR government in exile to obtain intelligence from Ukraine. They were looking for new people and new, non-standard ways to penetrate Soviet territory. Therefore, there was an opportunity to involve escapees in this work. They were first sent to an internment camp in Kalisz. There, representatives of the UPR intelligence created living conditions for them and began special training to send them to Soviet territory with an intelligence mission.

A few months later, they took the train to Rivne, where they were met by the head of the intelligence station, Ivan Lytvynenko. An experienced colonel of the UPR Army and an underground fighter, before sending them on a mission to the territory of the USSR, tested them. He asked in detail about the circumstances of the arrest, escape, and stay in the camp. Finally, he showed the insignia of the Solovki camp guards. And only after making sure that they are who they pretend to be, he moved on to the next stage of the operation to send them abroad. Such precautions were not in vain, because the GPU intensified the activities to introduce their agency in the ranks of Ukrainian emigrant centers.

I. Lytvynenko arranged both couriers’ illegal body crossing in early July 1932 near Korets. He handed each of them 1,000 rubles, 2,000 copies of leaflets, a revolver with ammunition, forged documents and an address for sending the collected information.

At that time, one of the most important tasks of the UPR's intelligence was to collect information about the situation in villages and about the Bolshevik policy that had led to famine and the extinction of the population. With this in mind, the couriers were given appropriate instructions. Here is what Hryhoriy Mamchiy testified about in the record of interrogation of January 3, 1933:

“As for working in the village, I received the following instructions:

First of all, Chykalenko drew the attention of me and other emissaries who were sent to Ukraine to the forthcoming grain procurement campaign, against which we had to campaign ourselves and through members of insurgent organizations. At this, it was necessary to explain to the villagers that non-fulfillment of the grain procurement plan or even its deliberate postponement would lead to great difficulties for the Red occupiers.

In addition, Chykalenko instructed me to carry out appropriate work to disrupt the sowing campaign. He suggested emphasizing the attention of villagers to the need to sow less, especially those crops that are exported, and to sow more areas with crops of local importance exclusively for their own use”(BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F.1. - Case 12628. - Vol.5 – P. 174).

Of course, after his arrest, these testimonies were written by G. Mamchiy under the dictation of the Chekists, who in the interrogation records called him “an agent of Petliura's intelligence who arrived in Ukraine from Poland for espionage and insurgent purposes”.

During Hryhoriy's time to study the situation in villages, he managed to get to his native village of Khrystynivka in Cherkasy region. There he hid at his mother-in-law’s. He secretly met with family, old friends and acquaintances whom he could trust, in particular, with Volodymyr Babiychuk. According to archival documents, "Babiychuk spoke about the situation in the village in very dark colors, that the villagers were starving, there were even deaths from starvation, taxes and grain procurement were unbearable, and all together created a situation where the villagers almost openly expressed hostility to the Soviet government." (BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F.1. – Case 12628. - V.5. - P. 178).

To send such information abroad, Ivan Lytvynenno once gave Hryhoriy his address and taught him how to do it in conventional phrases. In particular, “to write about a bad harvest that is good, to write the opposite about the bad mood of the population, to write about good soil and the results of the organization of insurgent centers, that mushrooms grow after the rain, etc”. There is no information in archival documents as to whether he managed to write at least one such letter and its content.

Instead, it is said that H. Mamchiy's old acquaintances from the surrounding villages with whom he met were wary of distributing the leaflets and arranging a meeting with the leaders of the underground counterrevolutionary committees. There were no such people, or they were afraid to talk about it, not trusting him completely. Evidently, fear weighed on people no less than hunger.

Hoping to find the underground, he decided to stay in Ukraine for a while. He soon learned of Semen Surzhko's detention. Later, Hryhoriy was arrested by police in the village of Yanove as he was heading to Korosten, intending to cross the Ukrainian-Polish border and report on the fulfillment of the task. A criminal case was instituted against him, several interrogation records from which have been preserved in the archives of the Intelligence Service. There is no information about his further fate in the case file.

Of course, in the conditions of a brutal totalitarian regime, when the slightest opposition to the policies of the government was ruthlessly stopped, when people were forbidden to leave the territories affected by famine, and some settlements were blocked by police, army and state security, it was difficult to conduct intelligence work. As a result, many people sent to Ukraine with similar tasks were arrested by the GPU, shot, or sentenced to various terms in jail. They also added to the multimillion list of those absorbed in those years by the Holodomor in its various manifestations and images.

(BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F.1. - Case 12628. - Vol.5 – P. 172–175)

(BSA of the SZR of Ukraine. - F.1. - Case 12628. - Vol.5 – P. 172–175)