Stepan Skrypnyk. Khorunzhyi of the UPR Army, MP, Patriarch

4/10/2025

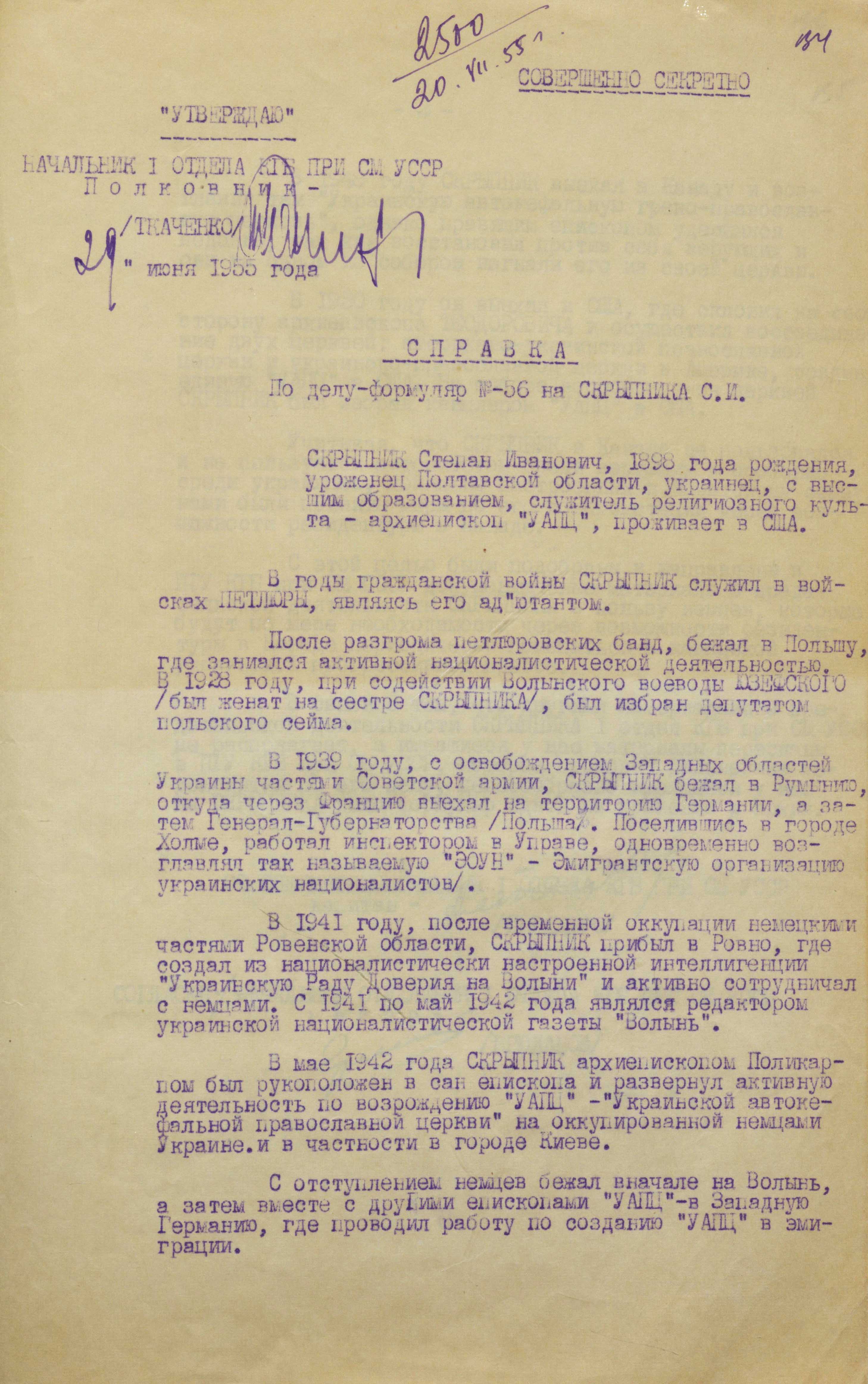

In the 1940s and 1980s, the kgb residentura in Canada and the United States widely practiced operations to compromise prominent Ukrainian figures who actively fought for spiritual and national revival through the so-called progressive press. One of such operations was directed against the then Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada, and soon the UOC of the USA, and in the future His Holiness Patriarch of Kyiv and All Rus-Ukraine Mstyslav. This is told by declassified documents from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine.

Symon Petliura's Adjutant

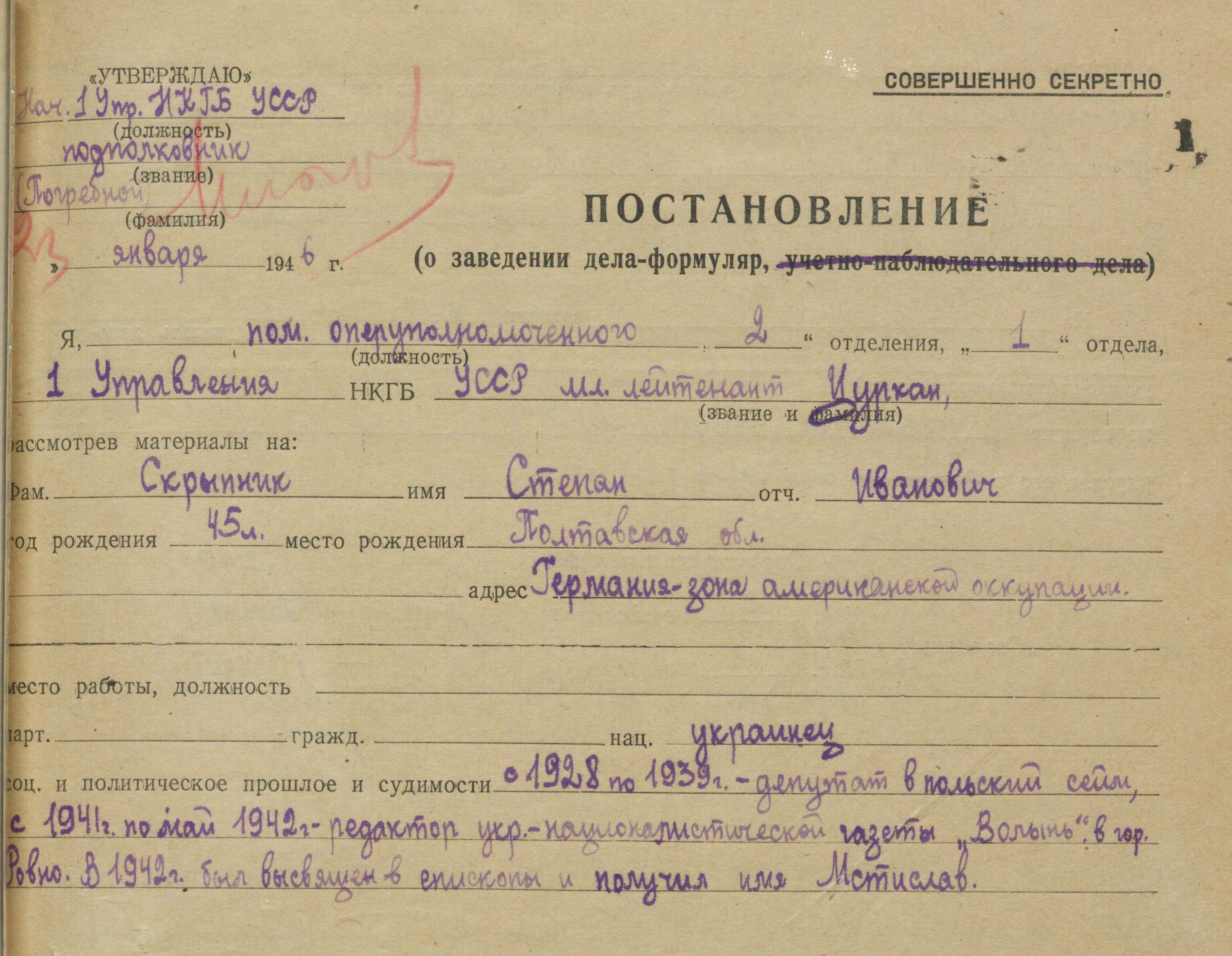

Stepan Skrypnyk’s operational case file which was processed for almost 40 years, was codenamed “Skorpion” by the kgb of the Ukrainian ssr. The sign of Scorpio in horoscopes is often perceived as mysterious and difficult to understand, embodying the mystery and boundless energy of existence, and people born under this sign are distinguished by their remarkable inner strength, will to win, and devotion to ideals. But the chekists were unlikely to delve into astrology that deeply. It was common practice to assign negative or ominous names to objects of operational development, such as: “Hyena”, “Spider”, ‘Jackal’, “Talentless”, etc.

At the same time, the first document attached to the case and dated October 4, 1944, contains an interesting characteristics of S. Skrypnyk and a certain mystery. “... When Bandera, with the blessing of Metropolitan Sheptytskyi, proclaimed an independent Ukraine in Lviv,” reported agent of the nkgb of the Ukrainian ssr “Ross”, “the former MP of the Polish Sejm, the famous Stepan Skrypnyk, came to Kyiv, where he was ordained a Bishop with the name Mstyslav. When Mstyslav (Skrypnyk) arrived in Rivne, I tried to see him. I happened to be in Rivne, and I visited him. We talked for about an hour. From this conversation, I became convinced that Bishop Mstyslav became a monk and bishop solely for the sake of becoming a prince in an independent Ukrainian state...” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case. 10345. – P. 2).

The chekists paid special attention to the last phrase, and they repeatedly returned to it in the future, tracking S. Skrypnyk’s rise in the church hierarchy. They were also greatly interested in his past. They found out that he was Symon Petliura’s nephew and even served as his personal aide. In exile, these family ties allegedly added to his credibility in the Ukrainian community. But the information about that period of his life in the file is rather scarce and fragmentary. Even the year of his birth is approximate - “in 1900-1905”.

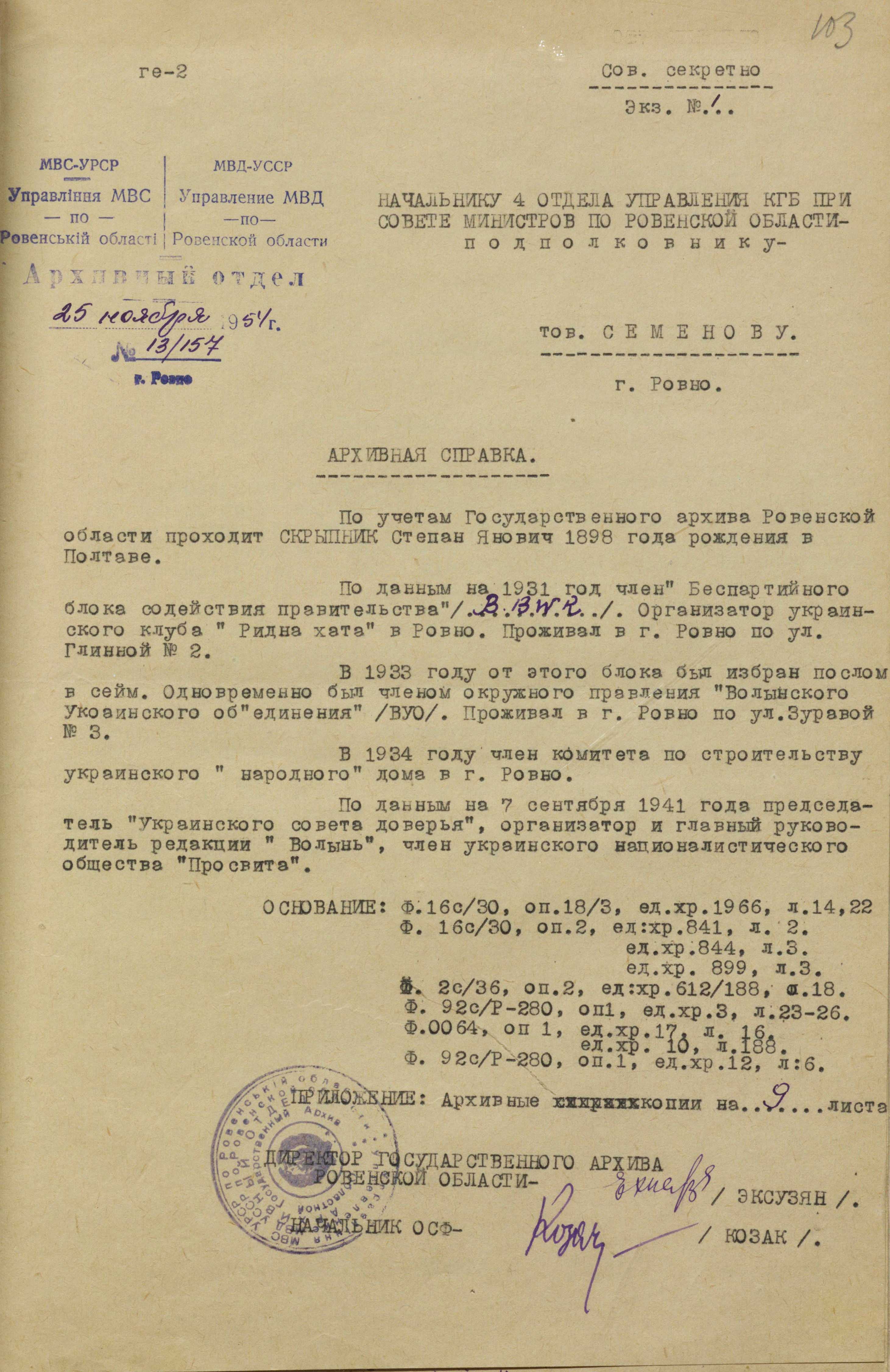

In reality, Stepan Skrypnyk was born on April 10, 1898, in Poltava. His father was from a Poltava Cossack family, and his mother was Symon Petliura’s sister. He studied at the Poltava First Classical Gymnasium, and soon afterward at an Officers’ School in Orenburg. In March 1918, he volunteered for the Kostiantyn Hordiienko Cavalry Regiment. In 1920, as a member of the 3rd Iron Division of the UPR Army, he participated in battles with bolsheviks and was promoted to a senior officer rank of Khorunjyi. In 1920-1921, he was the personal aide to the Chief Ataman of the UPR Army and Navy, Symon Petliura.

After the defeat of the liberation movement, he lived in exile in Warsaw. There he graduated from the Higher School of Political Science. In 1930–1939, he was a Member of the Polish Sejm from Ukrainians in Volyn. Using this status, he resolutely defended the interests of his compatriots. At that time, he became closer to the church. He took a course in theology at Warsaw University and worked with the episcopate and clergy of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.

There is no detailed information in archival documents about his work in the Polish Sejm. But then, checklists were not interested in that. “In 1939, with the liberation of Western Ukraine by the Red Army,” read the declassified documents, “Skrypnyk, along with other members of the Polish Sejm Ministry, fled to Romania, from there he went via France to Germany, and then – to the Governorate General. After living in Krakow for some time, Skrypnyk moved to the town of Kholm, where he worked as a self-employed inspector in the local administration and at the same time headed the so-called EOUN – the Emigrant Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists” (FISU. – F.1. – Dossier 10345. – P. 25-26).

The following documents relate to S. Skrypnyk’s life and activities during the Second World War. The chekists investigated that period especially thoroughly. And not without reason.

“ Find out Everything He Had Been Doing During the Nazi Occupation”

Immediately after the liberation of Ukrainian territories from Hitler’s troops, the nkvd began collecting information about what local residents had been doing under occupation. They were most interested in activists. S. Skrypnyk was among them. Here is what an eyewitness wrote about him: “With the occupation of Western Ukraine by the Germans in 1941, he came from the Governorate General to Volyn, to the city of Rivne. There, he organized “Ustanova Doviria” (“Institution of Trust” – Transl.) and the editorial office of the “Volyn” newspaper. The “Ustanova Doviria” was the Ukrainian supreme authority in Volyn. It was supposed to include representatives from all the district towns of Volyn. Therefore, in September 1941, representatives from the cities of Rivne, Kremenets, Dubno, Lutsk, Volodymyr, and Kovel were invited to a meeting in Rivne: Samchuk Ulas, Kornoukhov, Rostyslav Voloshyn... “Ustanova Doviria” did not do practical work in Volyn, because shortly after its organization, German civilian authorities arrived in Volyn and did not recognize the above-mentioned Institution” (FISU. – F. 1 – Case 10345. – P.7).

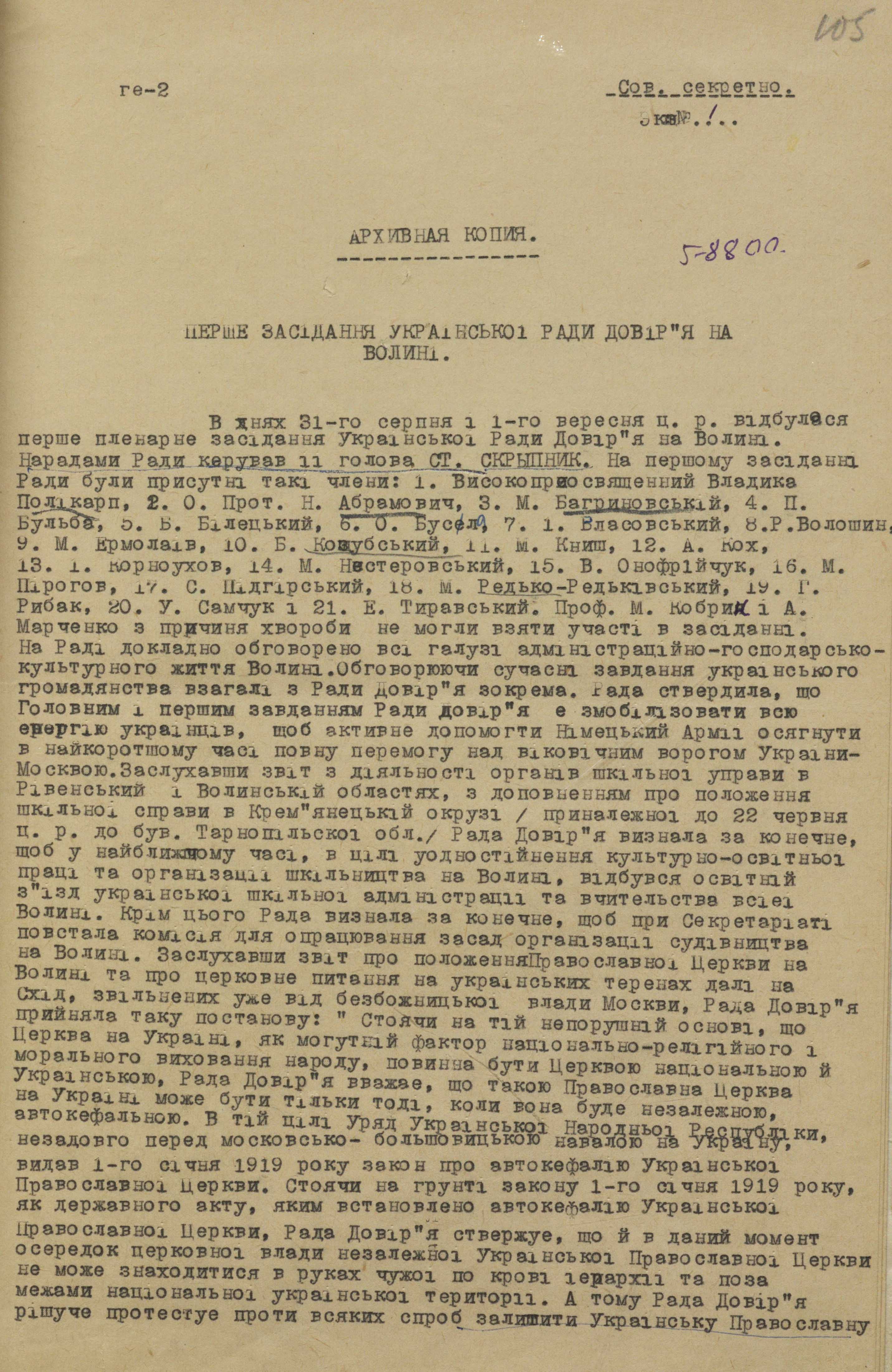

Archival documents contain information about the first meeting of the Ukrainian Council of Trust in Volyn chaired by S. Skrypnyk. The institution had exactly this name. The meeting discussed the organization of cultural and educational work, children’s studying at schools, gardening, etc. The issue of religious life and the position of the Orthodox Church was raised separately. Here is the text of the resolution regarding this issue. This text was included in the case file as evidence of S. Skrypnyk’s anti-soviet activities. Here is an excerpt from it:

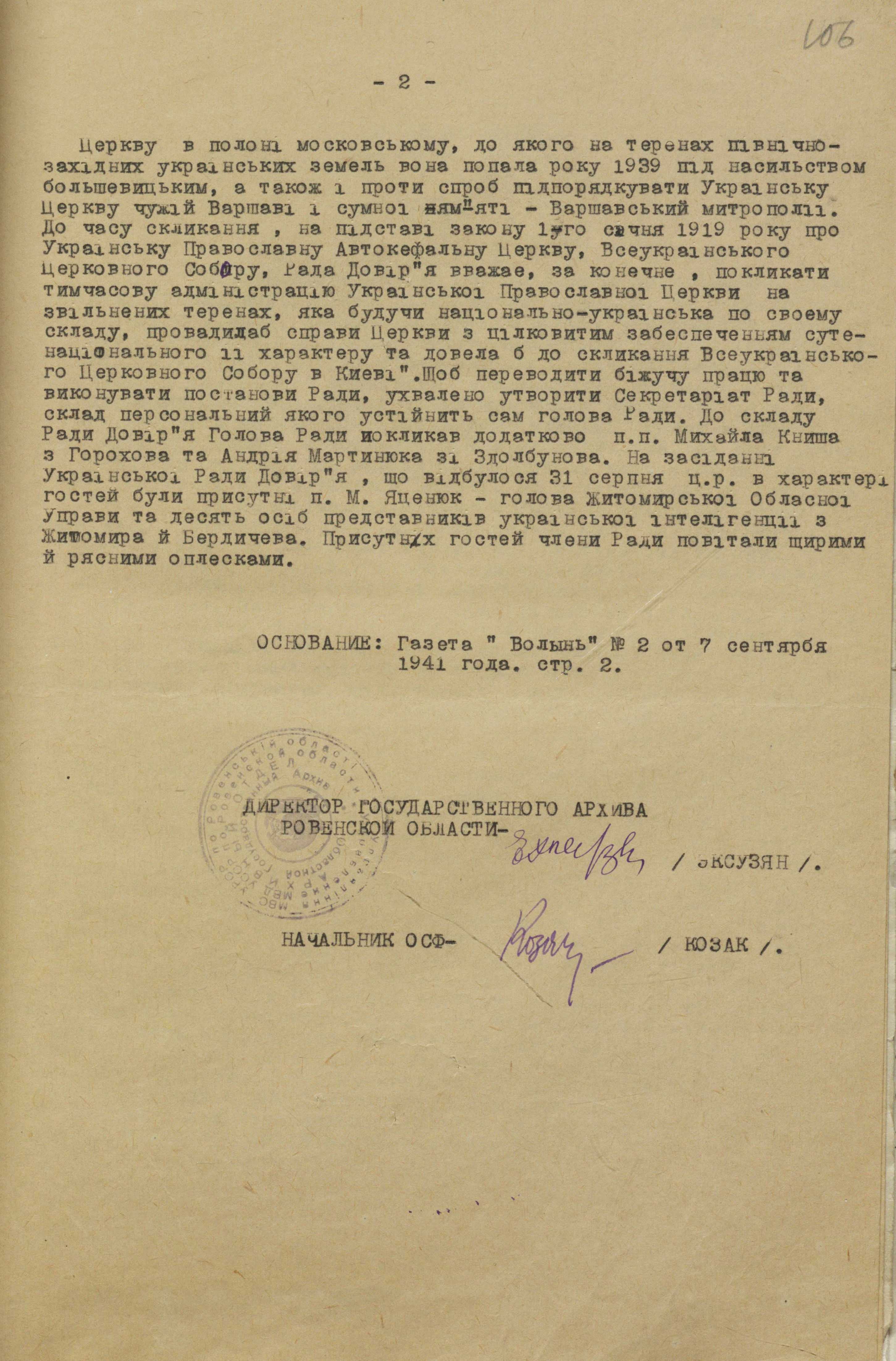

"The Council of Trust stands on the unshakable principle that the Church in Ukraine, as a powerful factor in the national-religious and moral education of the people, should be a national and Ukrainian Church. Therefore, the Council believes that the Orthodox Church in Ukraine can be such only when it is independent and autocephalous. To this end, the Government of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, shortly before the moscow-bolshevik invasion of Ukraine, issued a law on the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church on January 1, 1919. Based on the law of January 1, 1919, as a state act that established the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the Council of Trust asserts that even at the present time the center of church authority of the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church cannot be in the hands of a hierarchy alien by blood and outside the national Ukrainian territory. Therefore, the Council of Trust strongly protests against any attempts to leave the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in moscow’s captivity, to which it was taken in the northwestern Ukrainian lands in 1939 under bolshevik violence, as well as against attempts to subordinate the Ukrainian Church to the alien Warsaw..."

(FISU. – F.1. – Case 10345. – P. 105-106).

At that meeting, the “Provisional Administration of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church” was established, headed by Archiepiscopus Polikarp (Sikorsky).

Despite the task of the nkgb of the Ukrainian ssr to collect negative information about S. Skrypnyk, the documents contain positive characteristics as well. In particular, agent “Ivanov” among other things, reported as follows: “...Among the UAOC episcopate, he was the only one who stood out for his intelligence, capability of acting diplomatically, and for his character. Among the others, dull and faceless, only Mstyslav is a bright personality. In appearance, he is quite a representative person (he has black hair with some gray hairs, the same beard, has a strong body, his theatrical movements match his rank)” (FISU. – F.1. – Case 10345. – P. 37).

The report about S. Skrypnyk’s visit to Kharkiv in July 1942 did not quite fit the negative image of a “Germans’ fan ” created by the chekists. At that time, he met with the leaders of the local “Prosvita”, the Kharkiv City Council, and leading Ukrainian figures. Some advised him to pay a visit to the German commandant’s office and the Gestapo. “Mstyslav replied that this should not be done,” reads an excerpt from kgb agent “Sorbonin”’s report: “During the conversations, he very cautiously emphasized that not all German policies corresponded to the moods of Ukrainian public circles, that one should expect large and small conflicts, and that one should be prepared for everything.”

The agent further pointed out that when he was tete-a-tete with Mstyslav, the latter spoke more openly about how “the Germans massacred wonderful Ukrainians in Kyiv, that they intimidated people with that massacre, how wrong it is to believe that they are for Ukrainian statehood..., that now his and other Ukrainian senior clergymen’s situation is extremely difficult, since one has to be cunning and somehow build a policy with the Germans and at the same time take into account the masses’ enormous discontent with the Germans and support this protest and discontent if one wants to be a shepherd of his people and be honest with them”(FISU. – F.1 –Case 10345, – P. 37).

According to agent “Sorbonin”, shortly after this, representatives of the German occupation authorities ordered Mstyslav to leave Kyiv within 24 hours. Archbishop Polikarp allegedly entered into negotiations with the Reich Commissariat about a possible place of his ministry. The Germans offered Rostov, Luhansk, and Stalino. At the same time, Polikarp tried to obtain permission to serve as a clergyman in Simferopol, but in vain. “It seems that there was no response to this request,” reads the report, “and he disappeared, at least we do not know where to...”

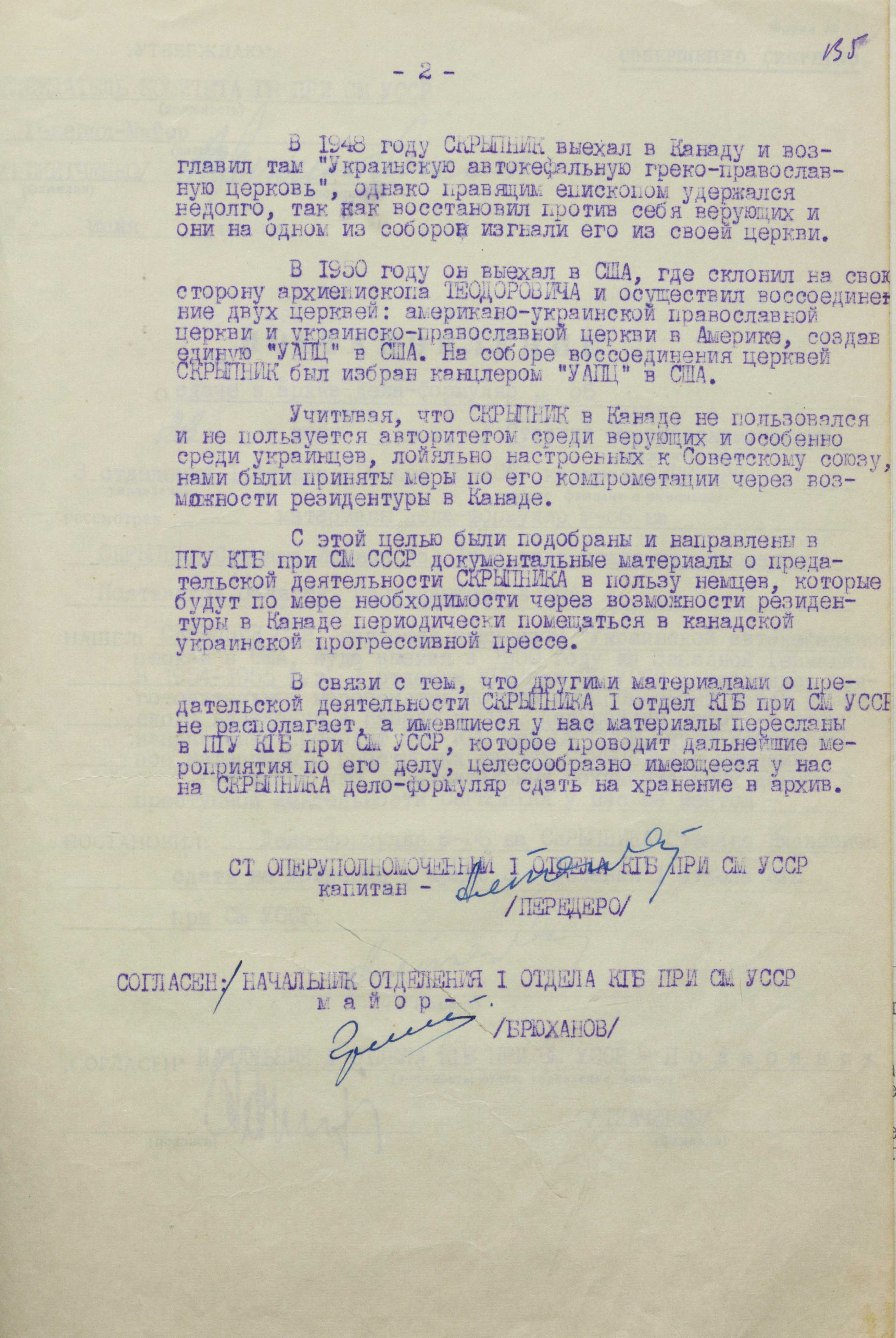

It is known from open sources that on October 12, 1942, Bishop Mstyslav was arrested by the Gestapo. During the German occupation, he served time in prisons in Chernihiv, Pryluky, and Kyiv. At the request of the clergy, he was released in April 1943. In 1944, he emigrated to Warsaw, then to Slovakia, and from there to Germany, where he headed the dioceses of the UAOC in Hesse and Württemberg. In 1947, he moved to Canada, where he was elected the first hierarch of the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church with the title of Bishop of Winnipeg and All Canada. Three years later, he moved to the United States. There, as noted in one of the kgb reports, “he won over Archbishop Teodorovych to his side and reunited the two churches: The American-Ukrainian Orthodox Church and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in America, creating a single UAOC in the United States. At the reunification council, Skrypnyk was elected Chancellor of the UAOC in the United States”.

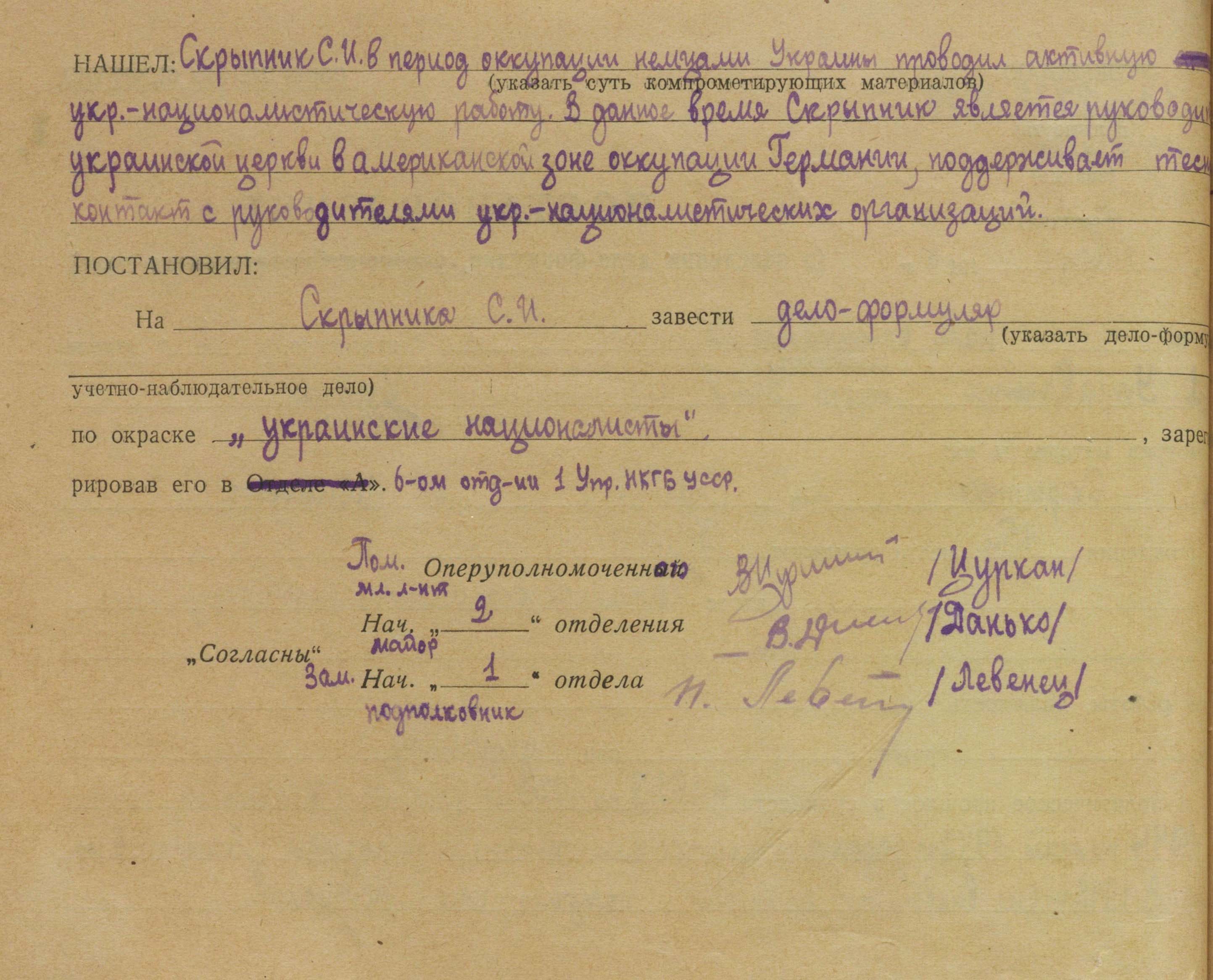

When investigating the reasons for Skrypnyk's leaving Canada for the United States, the Ottawa residentura of the kgb received information that the Metropolitan was allegedly not very favorably treated by some Ukrainian believers who were loyal to the ussr. That is, they did not accept his advocacy of the idea of the need for a separate unified Ukrainian Orthodox Church, as well as an independent Ukrainian state. They decided to play on this and take measures to compromise him through the capabilities of the kgb residentura in Canada.

A Plan to Compromize

Soon, a person was found to do the job. In the early 1950s, a correspondence perlustration service recorded several letters from Canada to a resident of a village in Ternopil region. As it turned out, a sister was writing to her brother, Davyd Karpiuk. In the letters, he told about his life, complained about certain problems, including unemployment and some other problems abroad. He pointed out that he was afraid to visit his friends in the United States, because if they found out that he was a communist, he could get into big trouble. At this, he praised the soviet power and stated that he had previously defended the ideals it proclaimed and would continue to fight for them.

In one of his letters he wrote: “I have one more request, if I may. Perhaps someone in the village knows Skrypnyk, the one who was in Borsuky, the secretary of the parish under Poland. He is a Bishop here in Canada and he lies a lot about the soviet power. I have already had a quarrel with him. I want someone to write me everything about him, what he had been doing under the Germans in your area. I would write about him in the newspapers here...” (FISU – F.1. – Case 10345. – P. 50-51).

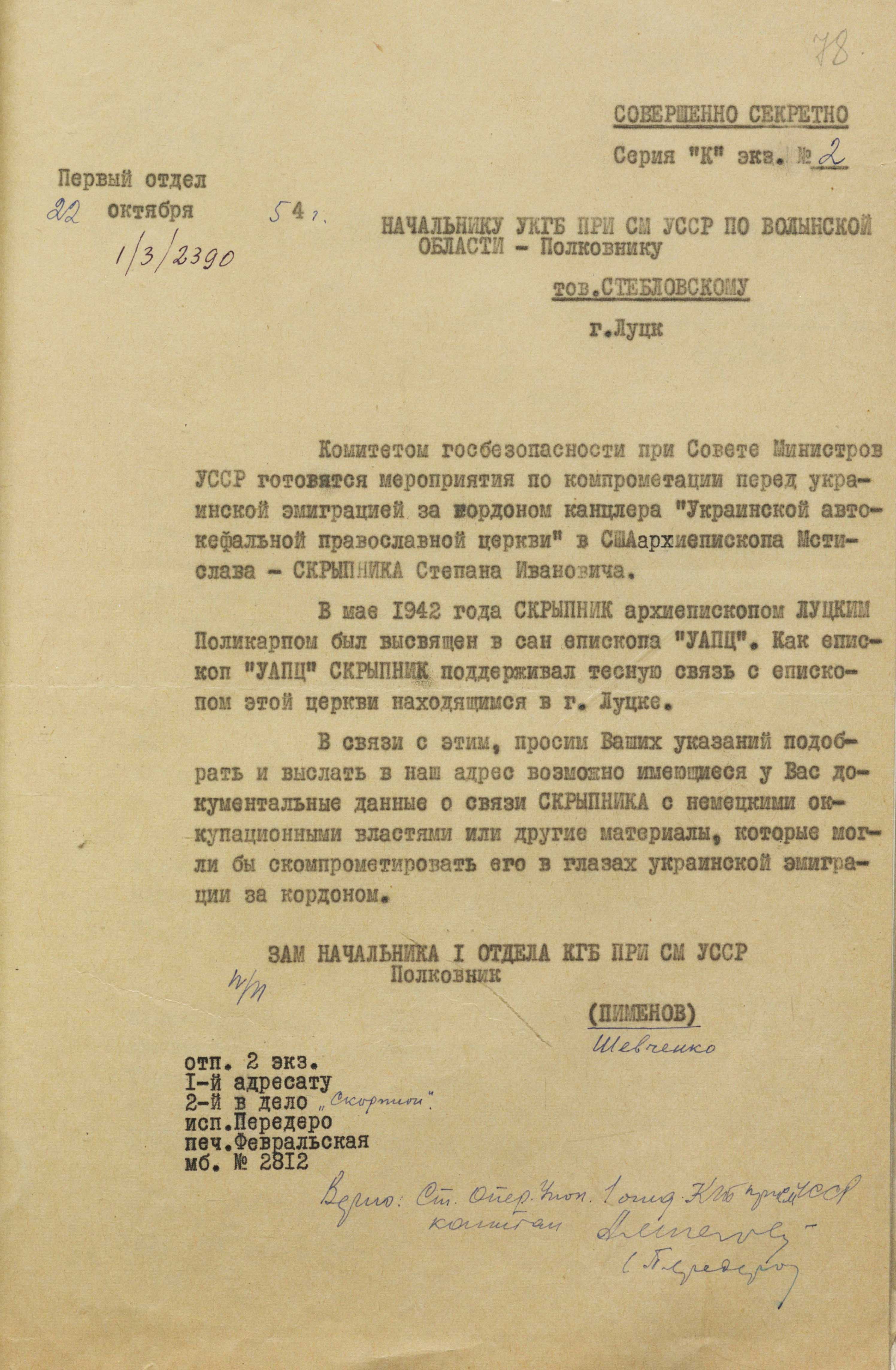

The kgb immediately seized upon the last phrase, and began to collect information on D. Karpiuk. Soon, the following instructions were sent from Kyiv to regional kgb directorates in Rivne and Volyn regions:

"One of the progressive journalists among Ukrainian emigrants living abroad intends to publish a number of articles aimed at compromising certain OUN leaders and subsequently publish them in a brochure for distribution abroad. In this regard, the kgb of the ussr has recommended that the author be provided with the necessary materials.

Attaching great importance to the possibility of debunking the ties of OUN leaders, as well as Uniate and Catholic authorities, with the Germans during World War II and their cooperation with foreign intelligences today, as well as the chance to demonstrate to emigrants the contradictions within the nationalist camp, the directorate of the kgb under the soviet of ministers of the Ukrainian ssr is selecting available materials on a number of OUN leaders and church leaders, in particular on Archbishop Mstyslav – S. Skrypnyk and other nationalist figures who operated on the territory of the region." (FISU. – F. 1 – Case 10345. – P. 146-147).

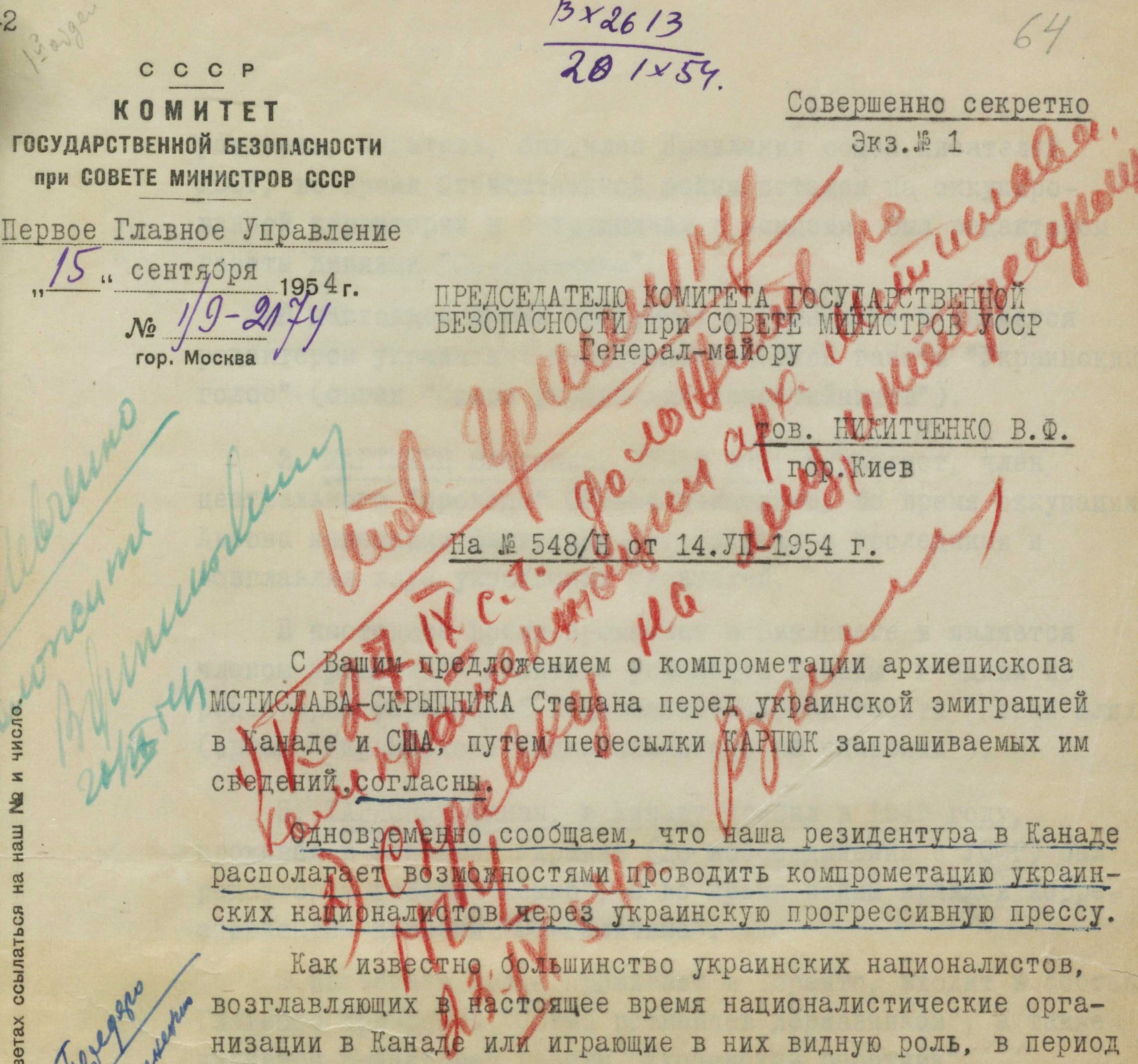

The fact that the collection of dirt had begun was reported to moscow. moscow chekists sent an approval of the planned activities. Moreover, they assured that everything would be done properly after the “incriminating materials” were received. “Our residentura in Canada,” reads the document, dated September 15, 1954, “has the ability to compromise Ukrainian nationalists through the Ukrainian progressive press... Skillfully selected documentary materials (orders of the occupation authorities, newspaper articles, leaflets, calendars, photographs, etc.) published in the Canadian Ukrainian press would play a huge role in compromising and discrediting these individuals...” (FISU. – Ф.1 – Case 10345, – P. 64).

Kyiv was not informed about the details of how the residentura worked with D. Karpiuk or other representatives of the “Ukrainian progressive press”. They were waiting for the requested materials. Meanwhile, according to archival documents, responses began to come from the regions.

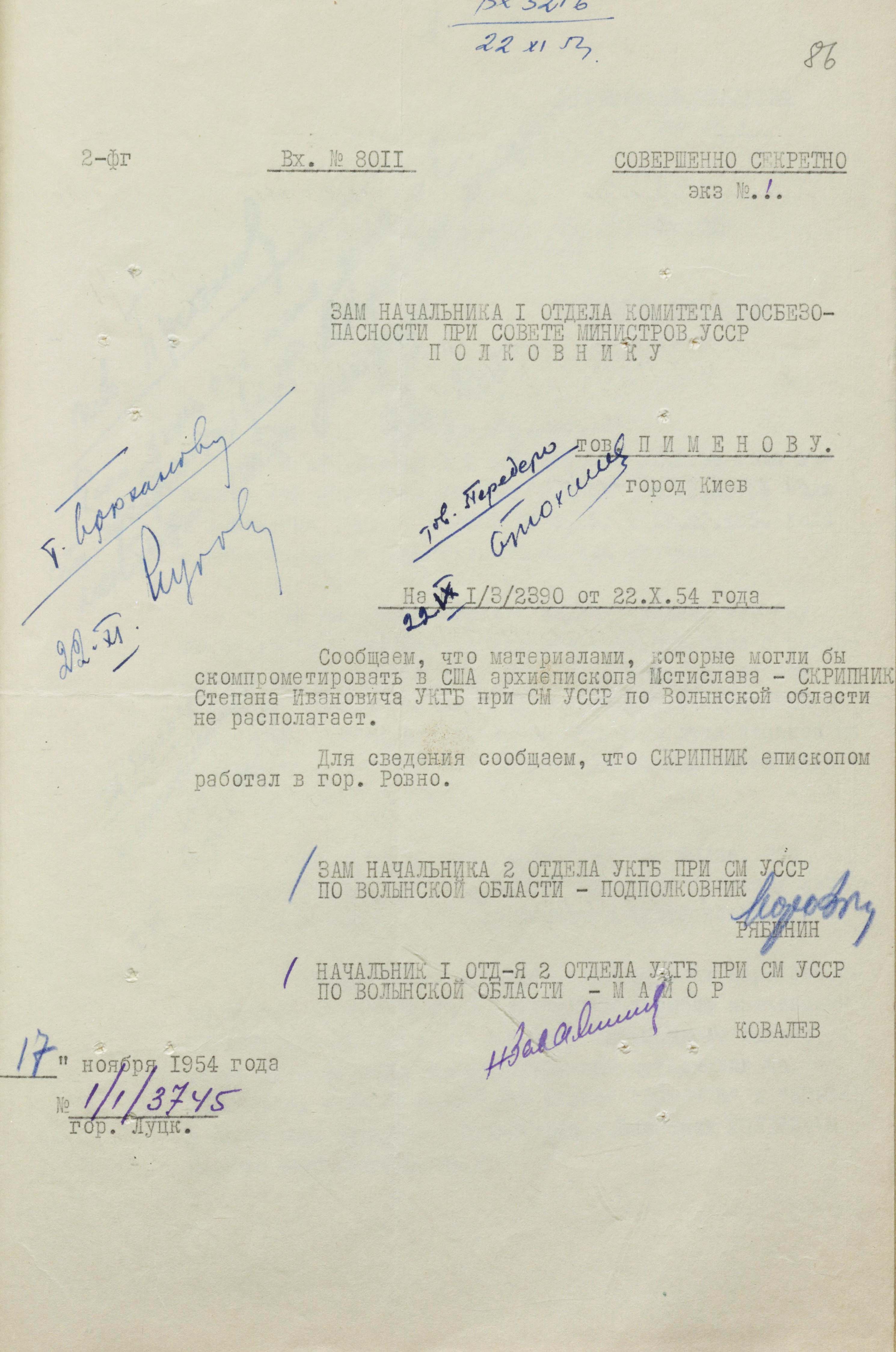

“We have no documentary information about Stepan Ivanovych Skrypnyk’s ties to the German occupation authorities,” reported the directorate of the kgb of the Ukrainian ssr in Kyiv region. “We are informing you that the kgb in Volyn region does not have any materials that could compromise Archbishop Mstyslav Skrypnyk in the United States,” – reads another response.

Only Rivne region sent a number of articles from Ukrainian newspapers of the period. They reported on S. Skrypnyk’s participation in the restoration of the Ukrainian church, creation of the “Institution of Trust” in Volyn, and other deeds. His words were quoted from publications in the “Volyn” newspaper, where he expressed hope that perhaps the Ukrainian people would finally be able to throw off the shackles of moscow’'s terrible Asian slavery, and “among the free peoples of New Europe, the Ukrainian people will take their rightful place.”

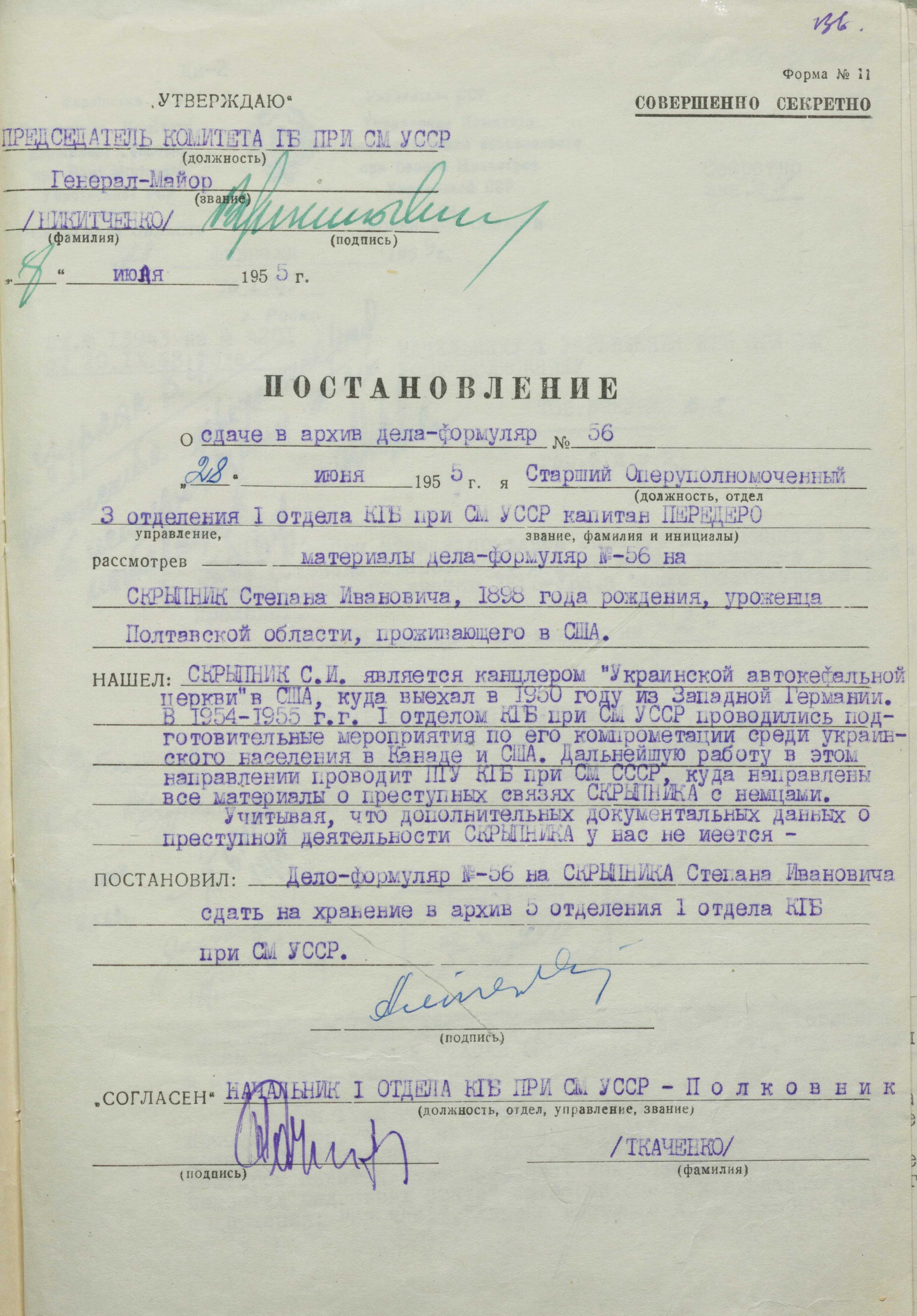

Moscow’s reaction to the materials sent was openly negative. They were not what was expected. The next instructions demanded to send at least the originals, not copies of newspaper articles or excerpts from them, if nothing else could be found. And indeed, according to archival documents, nothing else was found. Therefore, Kyiv approved a resolution on further operational cultivation of S. Skrypnyk: “In 1954-1955, the first department of the kgb under the soviet of ministers of the Ukrainian ssr took preparatory measures to compromise him among the Ukrainian population in Canada and the United States. Further work on this is being done by the first main directorate of the kgb under the soviet of ministers of ussr, where all materials have been sent... Given that we have no additional information about Skrypnyk’s criminal activities, the case file on Stepan Ivanovych Skrypnyk should be archived”. (FISU– F.1. – Case 10345. – P. 136).

Therefore, it is not known from the case file whether the kgb residentura in Canada managed to use the information collected. At the same time, practice shows that even if the chekists did not have enough of compromising materials, they would fill the gap with traditional groundless accusations of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism, espionage in favor of different countries, or other non-existent sins or crimes, among which the most important for the kremlin’s leadership were calls for restoration of a Ukrainian state and the Ukrainian Church independent from moscow.

But all those efforts of the kgb did not affect the authority of Stepan Skrypnyk in the church environment, not did they prevent him from defending Ukrainian interests. On October 30, 1989, he was proclaimed Patriarch of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in Ukraine and abroad. At the All-Ukrainian Orthodox Council in June 1990, he was elected UAOC Patriarch of Kyiv and All Ukraine. After the creation of the UOC-Kyiv Patriarchate in 1992, he was proclaimed its Patriarch. It was then that he also handed over the flag of the 3rd Iron Division of the UPR Army to the newly created Armed Forces of Ukraine.

One of Mstyslav’'s most significant achievements in the United States was the construction of the “Ukrainian Jerusalem” in America – the spiritual center of the Orthodox Ukrainian diaspora in South Bound Brook, New Jersey. It included St. Andrew’s Church, St. Sophia Seminary, a library, museum, consistory, retirement home, monuments to Metropolitan Vasyl (Lypkivskyi) and Grand Princess Olha, and a cemetery – pantheon of prominent Ukrainians.

His Holiness Patriarch Mstyslav of Kyiv and All Rus-Ukraine passed away on June 11, 1993. He was buried in the crypt of St. Andrii’s Cathedral in South Bound Brook.