Volodymyr Stakhiv. “Do Not Look for Allies at Any Cost, Even the Highest”

2/21/2025

After the split in the OUN ranks, the nkvd/mgb bodies of the ussr closely watched those figures who were distinguished by a fundamentally irreconcilable and unyielding position towards their opponents, were not afraid to object to leaders in their own circle, and openly expressed their opinions, even if they went against the generally accepted ones. Such people were actively cultivated in order to use their ambitions in chekists’ interests or to encourage them to take actions that would lead to an even greater split, discord, weakening, and eventually destruction of the national liberation movement. One of those who was subject to special attention in the 1940s was Volodymyr Stakhiv.

“Stakhiv Forbids Bandera to Be Bandera in the Future”

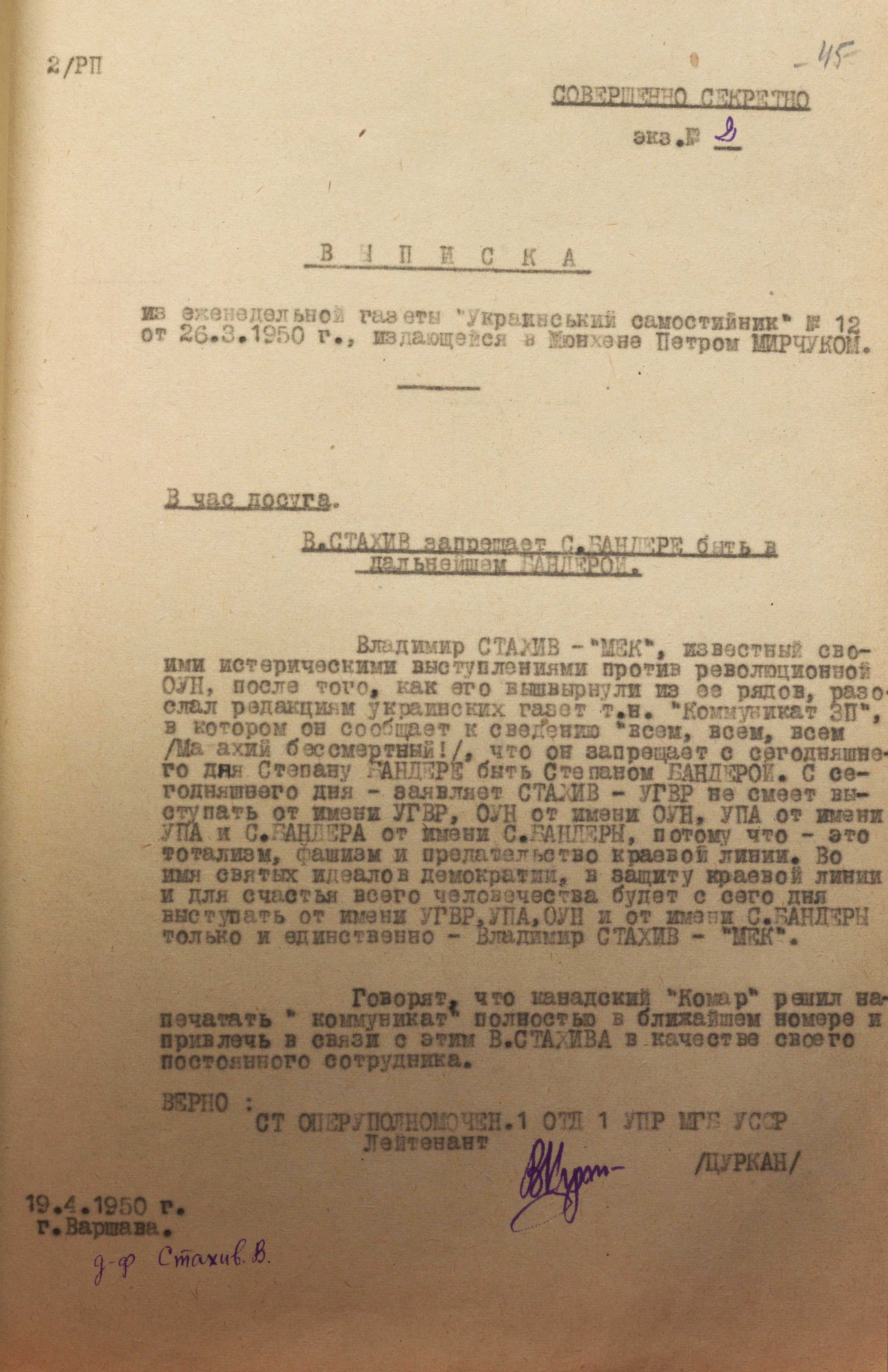

The case from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine, was opened by the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr in July 1946. Among the first materials included in the file there was a klip from the weekly newspaper “Ukrainskyi Samostiynyk” (“Ukrainian Independist” – Transl.) Issue 12 of March 26, 1950, published in Munich under the editorship of Petro Mirchuk. The article is entitled “V. Stakhiv Forbids S. Bandera to Be Bandera in the Future”. Among other things, it points out as follows:

“Volodymyr Stakhiv – “Mek”, known for his hysterical speeches against the revolutionary OUN, after being thrown out of its ranks, sent the editors of Ukrainian newspapers the so-called “Communiqué of the ZP [Foreign Representation of the Ukrainska Holovna Vyzvolnz Rada [UHVR – Ukrainian Main Liberation Council – Transl.]” (Malakhiy immortal!), in which he informs “everyone, everyone, everyone” that from now on, he forbids Stepan Bandera to be Stepan Bandera. “Starting today”, Stakhiv says, “the UHVR does not dare to speak on behalf of the UHVR, OUN – on behalf of the OUN, UPA – on behalf of UPA, and S. Bandera on behalf of S. Bandera, because this is totalism... For the sake of the holy ideals of democracy, for the protection of the borders and for the happiness of all mankind, from today on, Volodymyr Stakhiv – “Mek” – alone and personally will speak on behalf of the UHVR, UPA, OUN and on behalf of S. Bandera

(FISU. – F.1. – Case 11861.– Vol. 1. – P. 45).

Such categorical and excessive grotesqueness of V. Stakhiv is explained in other documents. One of them states that he “is one of the active oppositionists who sharply speaks against Bandera”, while another says that by his personal qualities he “is quite energetic and at the same time very hot-tempered”.

This is what the Chekists seized on and wanted to play on. However, the more materials accumulated in the case, the more obvious it was becoming that they would not be able to use Stakhiv in any of their games. Despite his hot temper, he was an experienced politician with strong convictions as a fighter for the restoration of Ukraine's independence, his own views on the methods of conducting this struggle, and an implacable opponent of moscow's enslavers. This was confirmed by biographical information collected about him at different times.

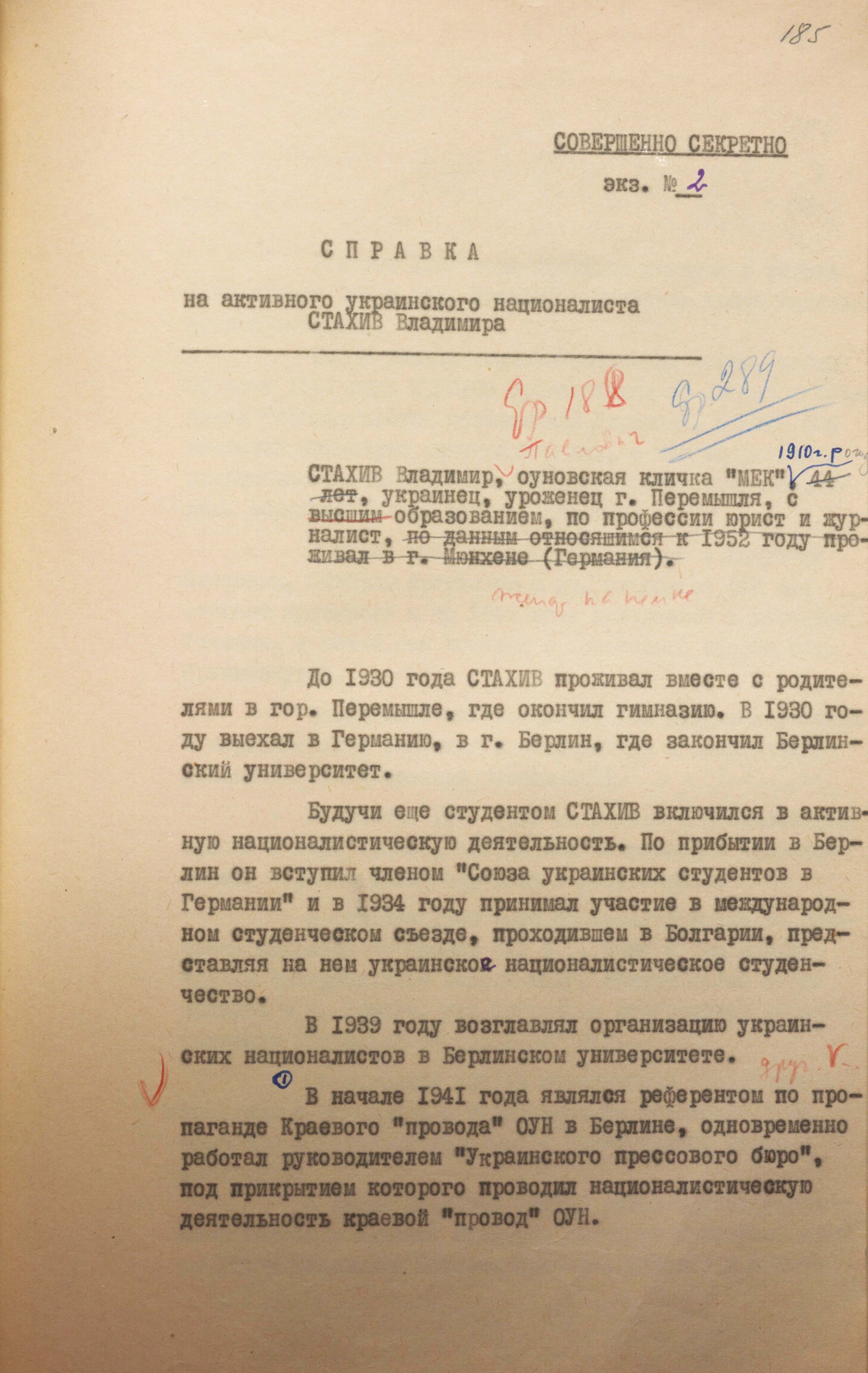

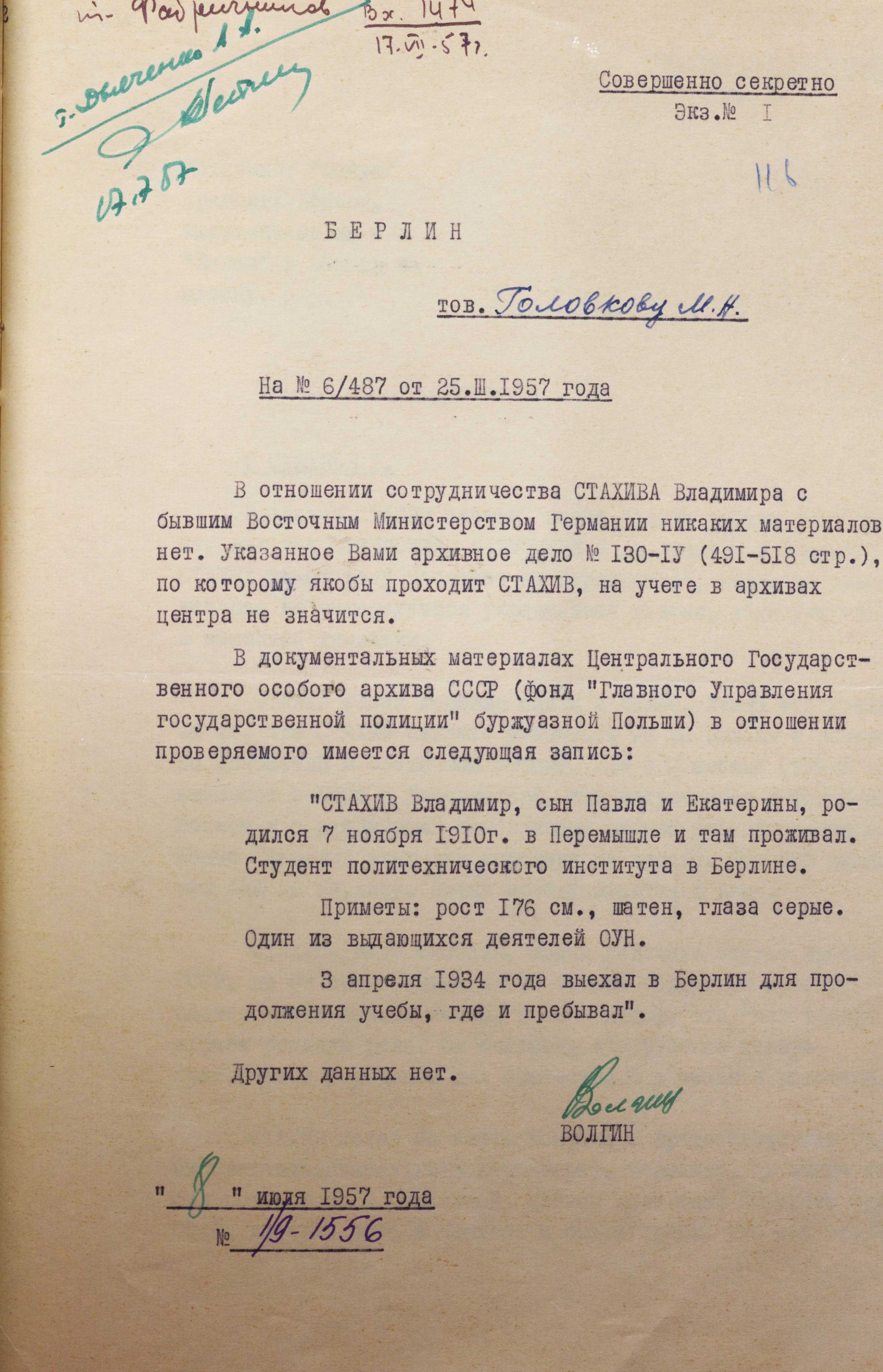

In the Central State Special Archive of the ussr, in the fund of the Main Directorate of the State Police of Poland, the following record was found for the 1930s: “ Volodymyr Stakhiv, son of Pavlo and Kateryna, was born on November 7, 1910, in Przemysl and lived there. A student of the Polytechnic Institute in Berlin. Description: 176 cm of height, brown hair, grey eyes. One of the most prominent members of the OUN. On April 3, 1934, he left for Berlin to continue his studies, where he stayed” (FISU. – F. 1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 3. – P. 116).

The exact date of birth is given here, which is not available on Wikipedia. At the same time, open sources point out that V. Stakhiv was born in the village of Bzovytsia (now a village in Zboriv urban community, Ternopil district, Ternopil region). In 1930, he graduated from a gymnasium in Przemysl, where he became a member of Plast, the OUN Youth, and then – of the OUN itself. Later he became the leader of the Peremyshl district OUN and after a while left for Berlin to study at the Polytechnic Institute.

At the same time, as shown by intelligence reports and other documents from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine, having graduated from high school, V. Stakhiv first went to Prague, not to Berlin. There he met leading OUN members Stsenyk, Stsiborskyi, Baranovskyi, Olzhych, Konovalets, and others. He studied at the Faculty of Social Sciences of a Ukrainian educational institution (apparently, the Ukrainian Free University, which was then located in Prague) and at the same time at the School of Journalism.

Zbigniev Kaminskyi, a member of the OUN's Foreign Units, in his own testimony to the Polish state security authorities wrote the following about V. Stakhiv:

“I should admit that he was a capable and resourceful person, so he quickly gained the trust of the OUN leader, Colonel E. Konovalets.

After graduation, as the latter’s envoy and confidant, in 1935-1937, he left Prague for Berlin, where Konovalets himself often visited...

A few days before Konovalets' death, on May 23, 1938, a reception was held in honor of Konovalets at the Japanese Military Attaché in Berlin, which was also attended by Volodymyr Stakhiv...

After Yevhen Konovalets’ death, V. Stakhiv stayed in Berlin and was one of Andriy Melnyk's employees...

From the moment of the split in the OUN into OUN-B and OUN-M in February 1940, V. Stakhiv, although during the entire period before the Second World War he had been abroad, was on the side of the OUN-B...

I know little about the period from June 1941 to November 1944. I do know though that V. Stakhiv was arrested by the Nazis for some time...”

(FISU. – F. 1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 1. – P. 249-252).

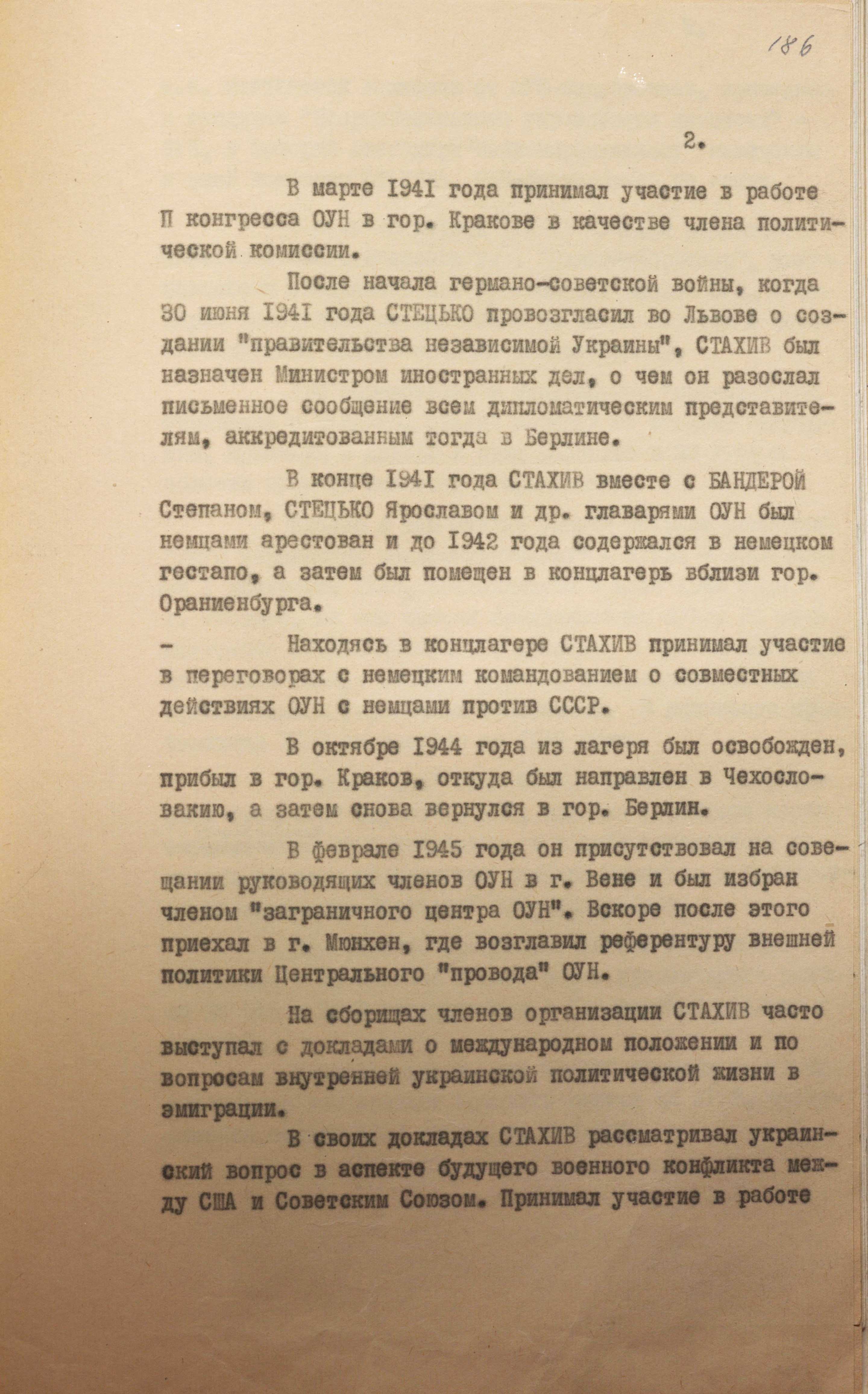

The mgb received information about that period from other sources. It found out that on June 30, 1941, V. Stakhiv was among the leaders headed by Yaroslav Stetsko who proclaimed the Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State in Lviv. Archival documents refer to the appointment of V. Stakhiv as a member of the provisional Ukrainian State Board. In other words, he was instructed by the government to “carry out a revamp of foreign affairs” in the rank of Minister.

But the government's activities did not last long. After leading OUN leaders rejected the Germans’ demands to withdraw the Act, they were arrested by the Gestapo and soon found themselves in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Together with Y. Stetsko, S. Bandera, and others, V. Stakhiv was also imprisoned in the camp. It is noted that in October 1944 he was released, and in February 1945 he participated in a meeting of the leading members of the OUN in Vienna and was elected a member of the OUN Foreign Center. Shortly thereafter, in Munich, he became the Chief of the Foreign Policy Referentura of the OUN Central Provid.

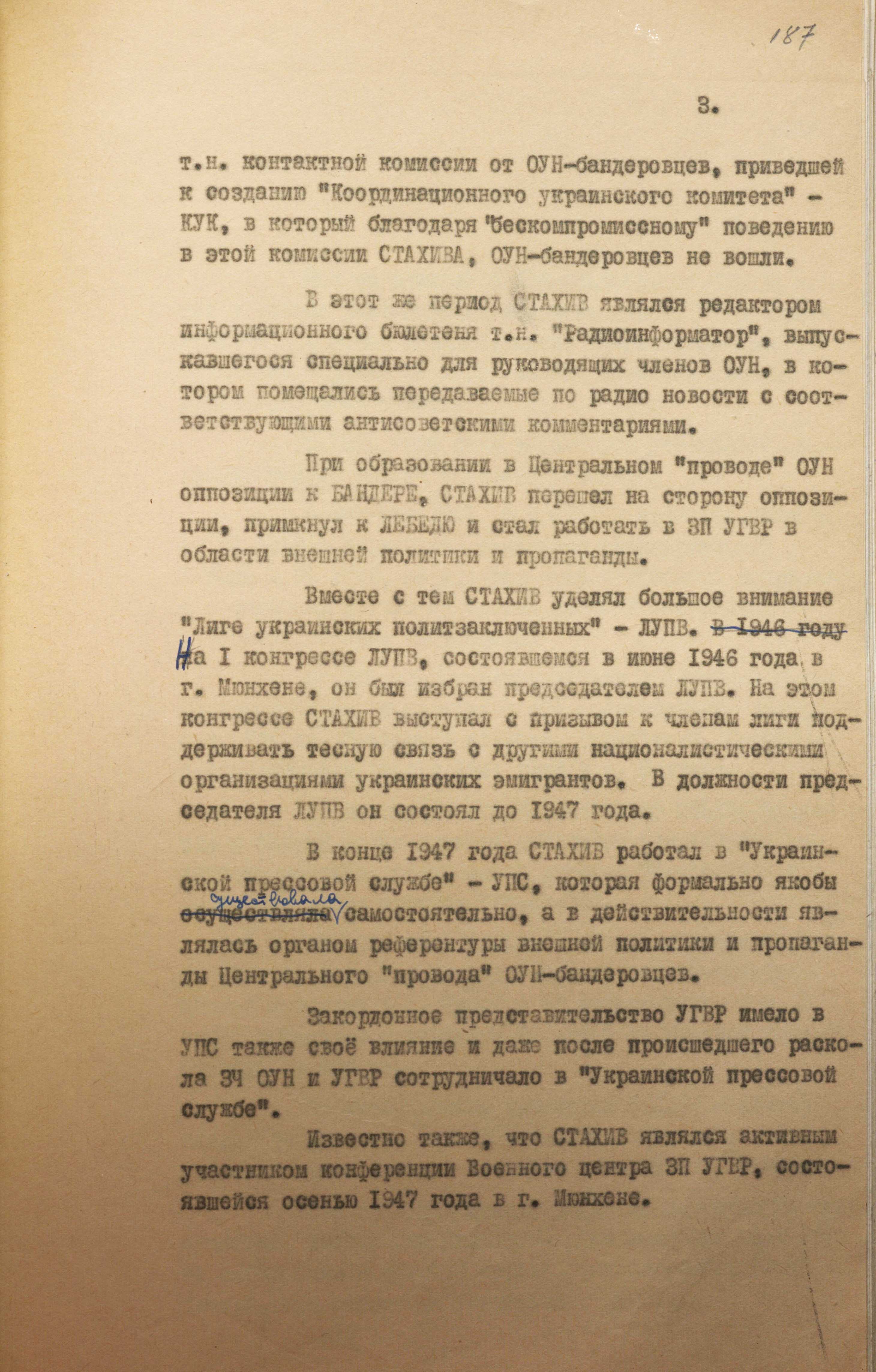

The second half of the 1940s was decisive in shaping V. Stakhiv's political views, sympathies, and leadership traits. According to archival documents, in June 1946 he was elected Head of the League of Ukrainian Political Prisoners at the first conference of the Organization. He served as the head until 1947. After that, he worked in the Ukrainian Press Service, which, as pointed out, “formally allegedly existed independently, but in reality was the referentura’s body for foreign policy and propaganda of the Central Provid of the OUN-Banderites.”

At meetings and in the press, he often delivered vivid speeches and articles on the international situation and on issues of domestic Ukrainian political life. He was a sort of a tribune, and the mgb agents could not help noticing that. They were watching his activities, but they didn't know what to do about it. After all, he was a rather extraordinary and unpredictable personality. So they were just looking closer at him to understand how his views were evolving and behavior was changing.

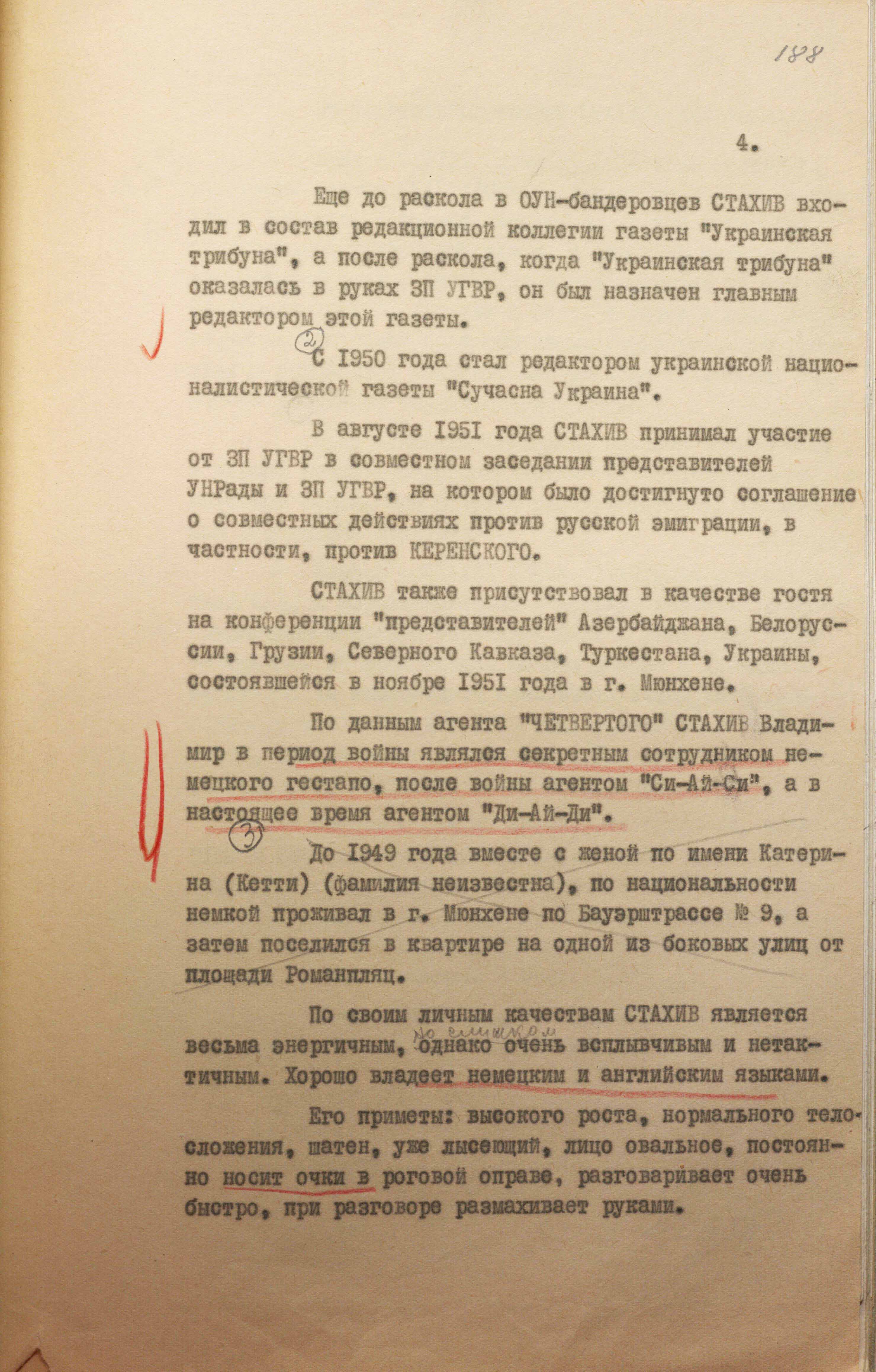

Meanwhile, his behavior remained as active as ever, but his position began to change in corse of his rapprochement with Lev Rebet, Mykola Lebed, and other OUN leading figures who in 1948 opposed Stepan Bandera’s authoritarian ideas. Even before the split in the OUN-B, Stakhiv was a member of the editorial board of the “Ukrainska Trybuna” newspaper. The struggle for this newspaper became the main one at that moment. It was widely publicized and even got into the mgb’s operational reports. Here is how Z. Kaminskyi described it in his testimony:

“...The leadership of the OUN Foreign Units wanted to completely seize the editorial office of the “Ukrainska Trybuna” and thus get rid of such people as V. Stakhiv, Pasichnyk, Dr. Lev Rebet, and others, who had gone over to the side of the opposition group... The opposition group in the office of the “Ukrainska Trybuna” at 9/11, Dachauerstrasse had no doubt that the OUN Foreign Units would seek to completely seize the newspaper, if only because after the second conference the newspaper opposed the OUN Foreign Units. Indeed, in the autumn of 1948, Ivan Vovchuk, one of the chief editors of the “Ukrainska Trybuna”, wanted to seize the editorial office by force, demanded the keys to the cash registers, etc. The argument resulted in a rather heated exchange of words between the editors of both sides. Volodymyr Stakhiv, in order to compromise the representative of the OUN Foreign Units, ran out of the editorial office into the street, made a fuss and called the German police under the pretext that unknown persons had broken into the editorial office of the “Ukrainska Trybuna”. After clarifying all the circumstances, the police tried to calm down the arguing editors. A scandal erupted out of all this, which prevented the OUN Foreign Units group from seizing the editorial office”.

(FISU. – F.1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 1. – P. 254-255).

At the same time, as noted in the document, the OUN Foreign Units, with the help of their organizational network, on which the newspaper's distribution depended, stopped selling the “Ukrainska Trybuna”. As a result, the newspaper soon went bankrupt and closed down altogether. The mgb, which was closely monitoring the developments, drew certain conclusions from this. Hence, in the measures planned to reduce the influence of “anti-soviet propaganda from foreign Ukrainian nationalist publications,” there were clauses that provided for sending agents to cause disorder among the editors of such publications. For this purpose, the task was to infiltrate the existing agents into editorial teams or recruit influential journalists.

According to archival documents, no such tasks were set regarding V. Stakhiv. It was obvious to the chekists that it was impossible to recruit such a person. He could only be assassinated. As was the case with Lev Rebet, who also worked for the newspapers “Ukrainska Trybuna”, “Chas”, “Suchasna Ukraina”, and headed the editorial board of the newspaper Ukrainskyi Samostiynyk”. He was one of the most powerful intellectuals in the OUN. It is not surprising that he aroused moscow’s special hatred and became the target of a special operation by the kgb of the ussr. Agent Bohdan Stashynskyi, whom Lubyanka tasked with his assassination, later admitted in court that the curators presented the victim–to–be as a “theorist of political emigration” of Ukrainians, a prominent publicist, and emphasized that he was more dangerous to the ussr than Stepan Bandera.

Declassified documents of the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr do not contain any information on whether V. Stakhiv's murder was also planned. At the same time, the case file shows that at that time, the main operational cultivation was carried out by the Office of the mgb Commissioner under the state security authorities of the German Democratic Republic. From Berlin's point of view, it was more convenient and closer. Through this body, the ussr mgb conducted all operations to cultivate and assassinate M. Kapustianskyi, L. Rebet, S. Bandera and other OUN activists, and instructed action agents B. Stashynskyi and others. At this, operational documents were not always sent to the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr in Kyiv for further work on the cases after all the activities were completed. The vast majority of materials ended up in moscow.

The documents in the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine show that the process of studying V. Stakhiv continued throughout the 1940s and 1950s. After that, the mgb of the Ukrainian ssr decided to intensify his cultivation. The decision was dictated by the fact that the defendant in the case himself did not slow down his activity in political life, in particular in the printed word.

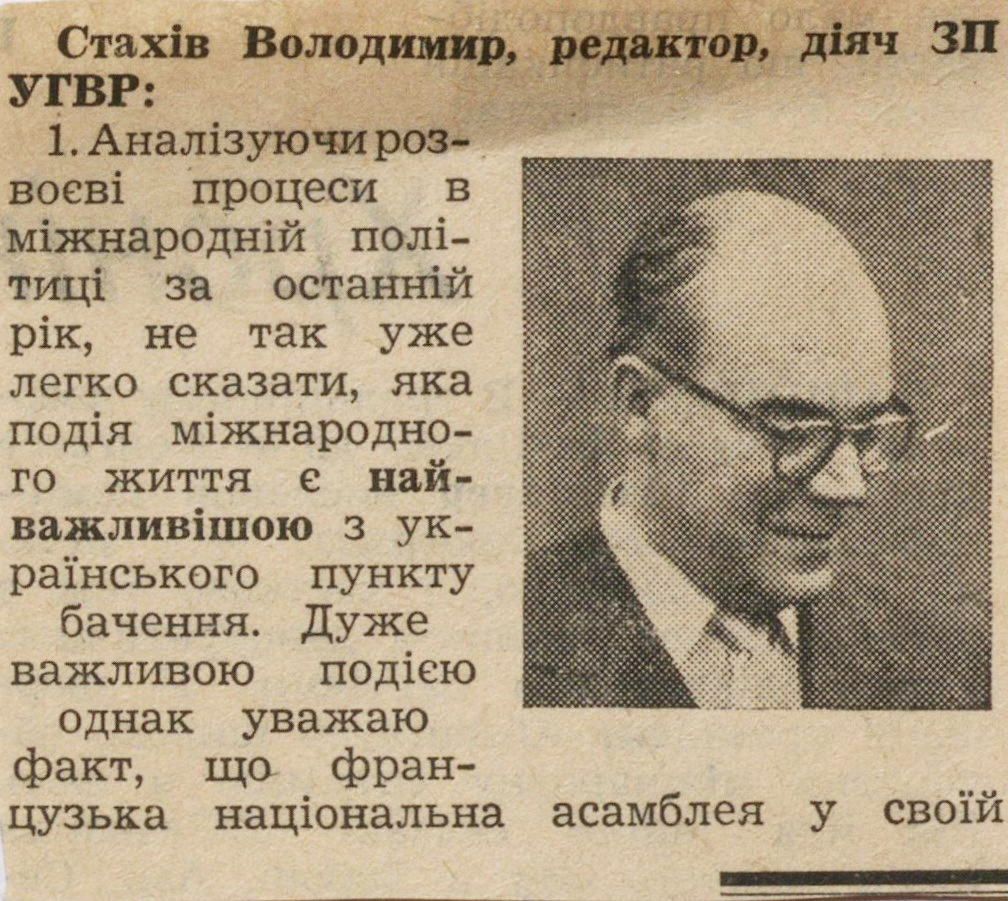

“At that time”, one of the mgb papers states, “Stakhiv was the editor of the so-called “Radioinformator”, a newsletter issued specifically for leading members of the OUN, which contained news broadcast on the radio with relevant anti-soviet comments...

In 1950, he became the editor of the Ukrainian nationalist newspaper “Suchasna Ukraina”.

In August 1951, Stakhiv participated on behalf of the UHVR in a joint meeting of representatives of the UNRada and Foreign Units of the UHVR, at which agreements were reached on joint actions against russian emigration, in particular against Kerensky”

(FISU. – F.1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 1. – P. 187-188).

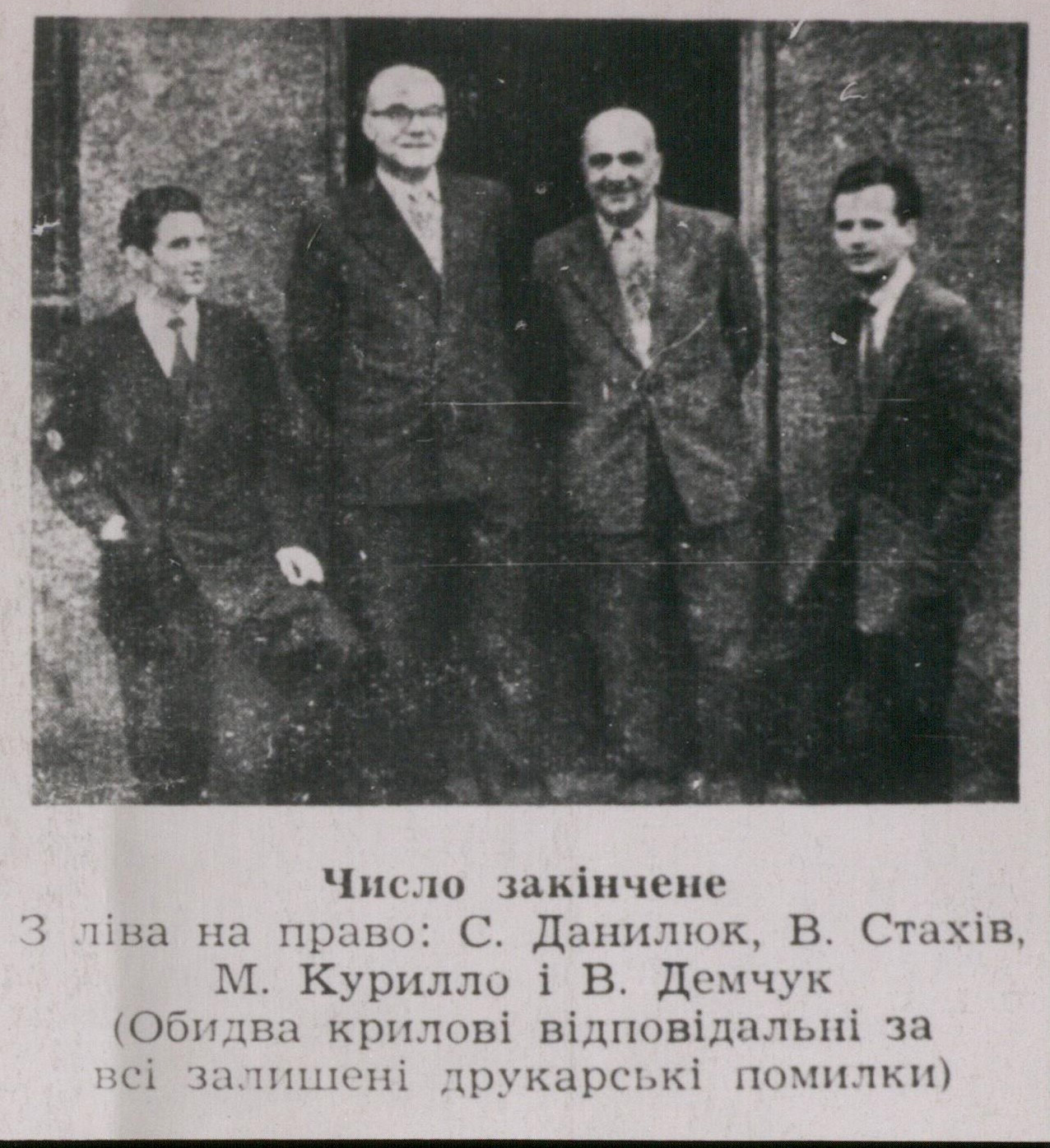

Editor of the Biweekly “Suchasna Ukraina”

V. Stakhiv’s activities as the editor of the biweekly “Suchasna Ukraina” were quite eloquently described by the already mentioned Z. Kaminskyi. He pointed out that V. Stakhiv also headed the departments of foreign and internal Ukrainian policy in the editorial office, and together with L. Rebet, – the programmatic and ideological direction of the newspaper. During his editorial work, he “managed to raise the newspaper to a decent level”. Regarding the journalistic level of the materials, Z. Kaminskyi wrote that “Suchasna Ukraina” was one of the best Ukrainian newspapers published in exile.

The case file contains a typewritten text of V. Stakhiv’s article from the newspaper of March 6, 1955. The article is entitled “Modern Opportunities for Ukrainian Foreign Policy”. In it, the author characterized the then current state of the Ukrainian issue within the ussr and in the world in general. He wrote that “the russian-bolshevik imperialists in moscow are forced to make concessions to the national consciousness and elements of the enslaved non-russian state peoples in order to keep them in the empire with some kind of vice grip and at the same time not to allow this element to overflow the official channel of the dominant political thought.”

V. Stakhiv pointed out that in the ussr there is a consistent attack of the national idea on the foundations of the empire and imperial thinking, which has already absorbed non-russian representatives in the party and the ruling elite. This process is slow, but it does not stop. At the same time, he drew attention to the fact that, in contrast, the kremlin leadership initially implemented a policy of restraining national consciousness by various methods, including bans, suppression of all kinds of manifestations, and even terror and murder. This was replaced by a phase of “reconciliation with national aspirations of non-russian peoples” and flirting with them.

On the other hand, V. Stakhiv analyzed other leading countries’ positions on the Ukrainian issue. He saw uncertainty in the USA’s policy as to how to build future relations with each national state that could be formed on the wreckage of the soviet empire. He characterized the concept of uncertainty at that time as a state according to which the solution to the question remained open and not fully understood. “It does not matter that this concept now still serves only as a “ probe”, he wrote, “but in the absence of a different idea, it should still be considered at least the penultimate word of the American attitude to the affairs of the European East. Therefore, the task of Ukrainian foreign policy is to ensure that the last word of American East European policy stops all previous experiments in this matter”.

The proposals of Great Britain, in his opinion, were grouped around the idea of “intermarium”, that is, the entry of Ukraine and Belarus into some federal or confederate formations, in which Poland had to be an active participant. Germany allegedly dreamed of conducting a revision in Europe after World War II, and Ukrainian lands could only become subject to bargaining and some concessions, but not a fundamental decision to create a sovereign Ukrainian state. France allegedly only tended to study Eastern European issues. “The role of France in deciding the future situation of Eastern Europe”, he wrote, “will be, compared to the recent past, somewhat more modest, but still influential... It is possible that the French will want to be experts and see this as their future role in resolving Eastern European affairs”.

At the end of the article, V. Stakhiv pointed out that all those realities of the current international policy had to be soberly perceived, without resorting to pessimistic sentiments, but looking for opportunities for resolving the Ukrainian issue in that situation, based on “national interests and real benefits for the liberation cause of Ukraine”. “Thanks to sovereign foreign policy”, he stressed, “not to go in the wake of other people's concepts, not to look for “allies at any cost”, even the highest. The task of foreign policy is to find sustainable solutions in mutual relations with neighbors and distant surroundings; seek and gain confidence in their work and in their political concept and line” (FISU. – F.1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 1. – P. 227–232).

There is the Ukrainian ssr mgb’s label “Secret” on the reprint of this article. The article was thoroughly analyzed and the conclusion was drawn that with such seditious thoughts and conclusions, its author is very dangerous for the existence of the ussr, and that these narratives, which he spreads in the information space abroad, greatly harm the “soviet national policy”.

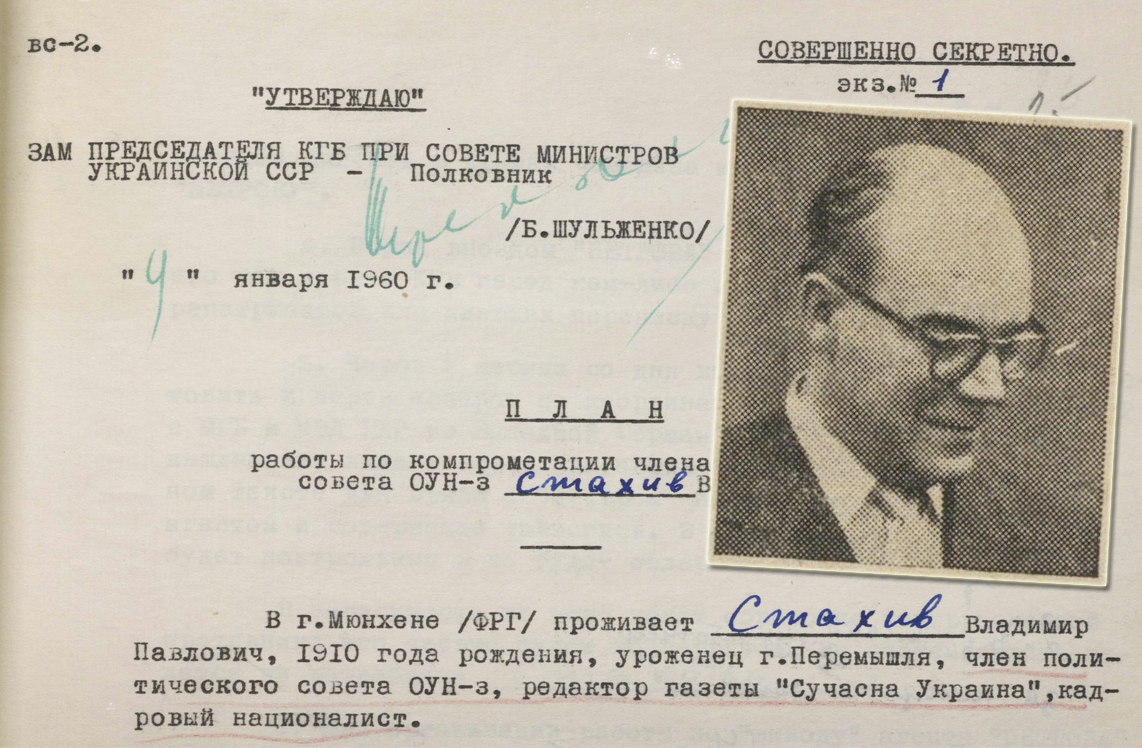

“Compromise V. Stakhiv As an Alleged Agent of the kgb”

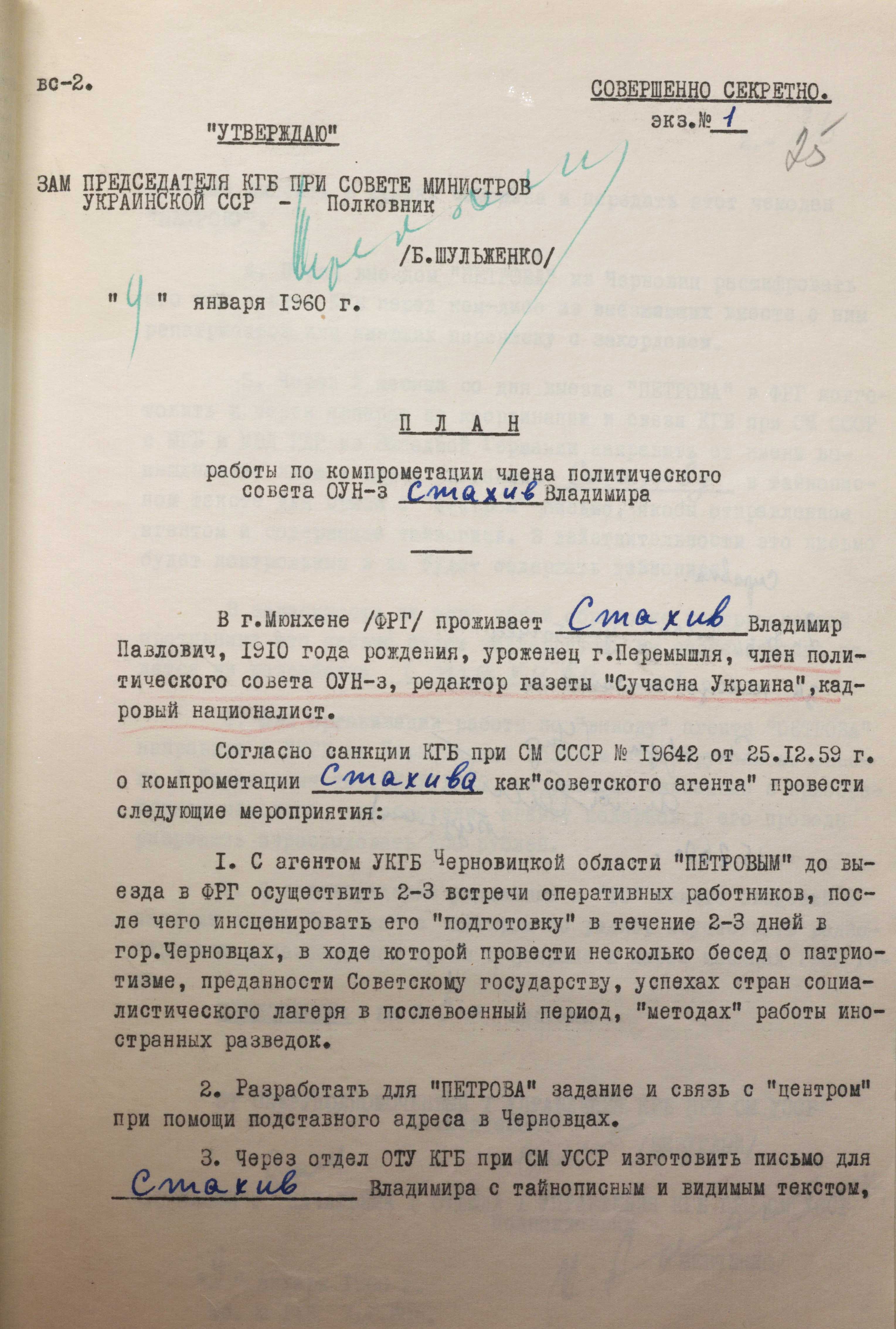

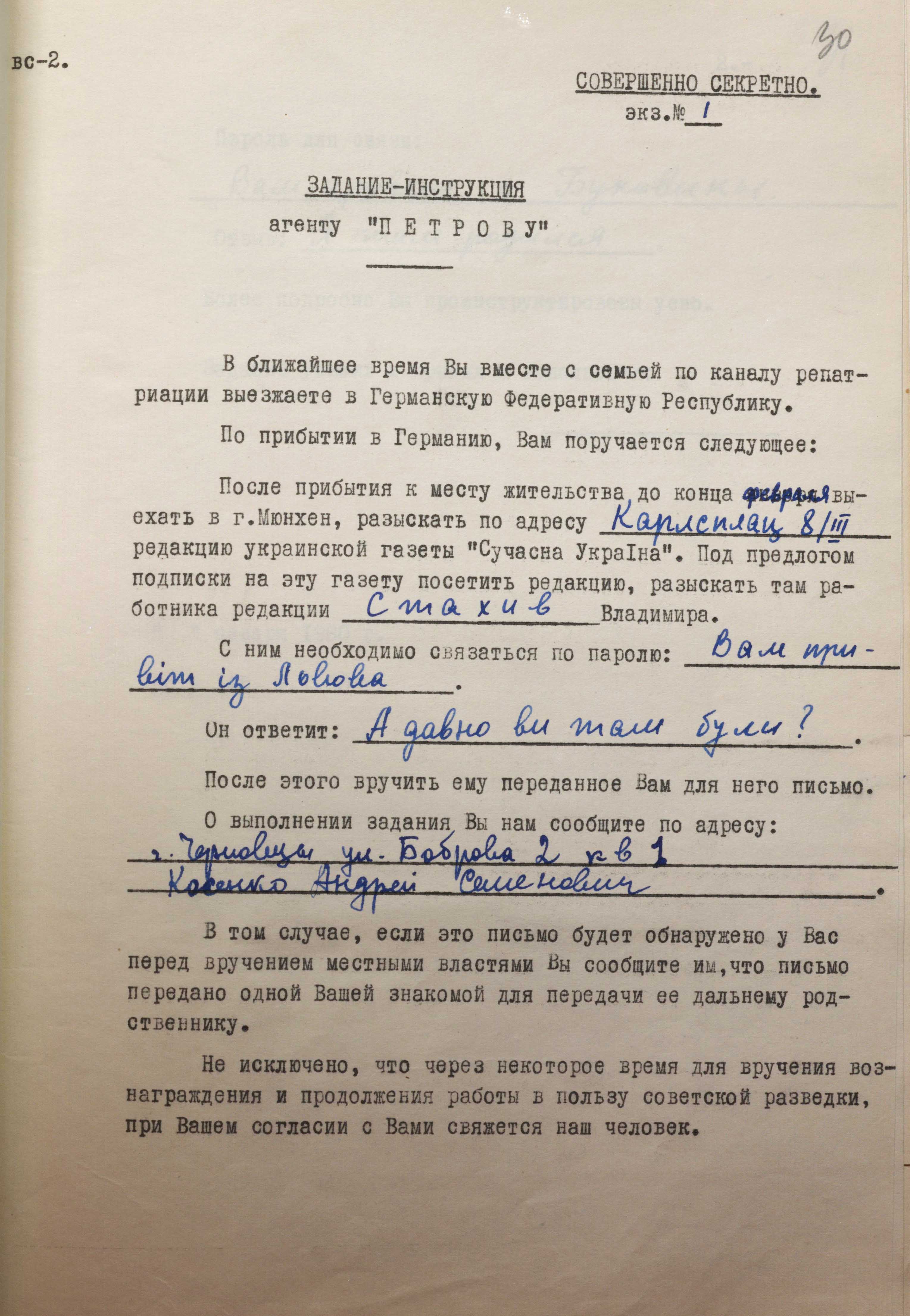

After considering a number of proposals on what to do with V. Stakhiv, in December 1959, the kgb decided to take measures to compromise him. The scheme was a familiar one that had been used repeatedly at the time: to compromise him in front of his close circle as an alleged agent of the kgb. To this end, they found a real archival agent, with code name “Petrov” who had applied to leave for Germany for permanent residence with his relatives as a repatriate. One of the papers on him stated that he was a Catholic fanatic opposed to the soviet regime, was insincere with the kgb from the very beginning, and told his wife and priest about everything, i.e., he disclosed himself. At the same time, this was exactly what was needed.

“In this regard”, the document said, ‘it is necessary to hold several meetings with “Petrov”, create an impression of trust in him, provide him with alleged assistance in leaving, and through him to pass over a letter to V. Stakhiv as an agent of the kgb. In this letter, in the secret writing of an outdated recipe, to report receiving important materials from him and give instructions for “events” that “had been agreed upon” during the festival in Vienna. In June-August 1959, Stakhiv met in Vienna with a group of tourists from Ukraine, kgb officers included. To inform him that his relatives were living in Przemysl, feeling well, receiving support from us...” (FISU – F. 1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 2. – P. 15).

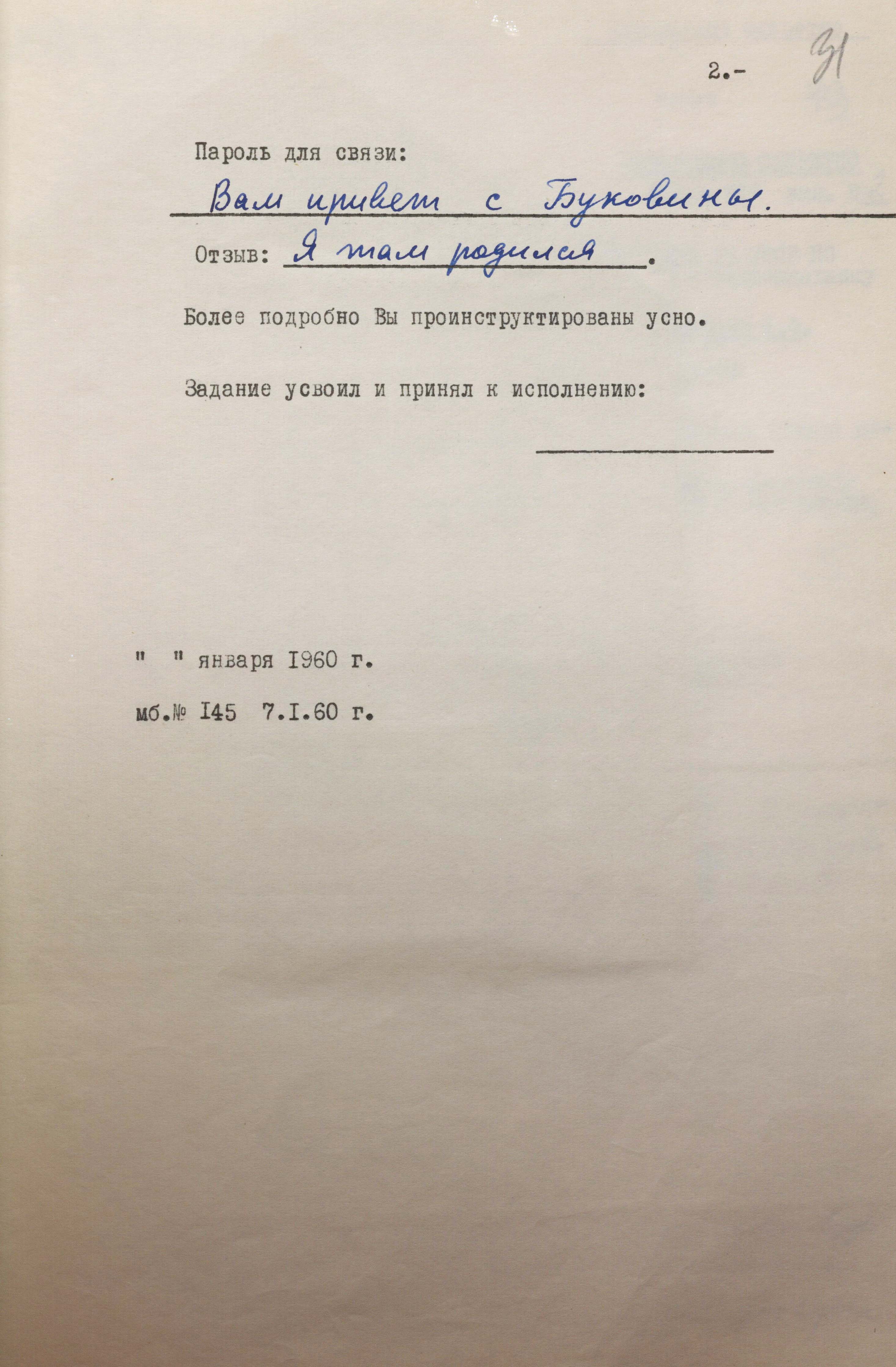

According to the assignment, upon his arrival in Germany, “Petrov” was to go to Munich, find the editorial office of the newspaper “Suchasna Ukraina”, and, under the pretext of subscribing, meet with V. Stakhiv and hand him the letter. In order to smuggle the letter across the border and give “Petrov” the impression that all that was of great importance and shrouded in great secrecy, the letter was hidden in the double bottom of a suitcase that had been purchased and handed to him specially for this purpose.

As an alternative, it was assumed that “Petrov” would not meet with V. Stakhiv upon his arrival in Germany, but would go to the police and tell them everything. This would become subject to further investigation, checking V. Stakhiv and casting a shadow of suspicion on him as someone who might actually be a kgb agent. Both options were acceptable.

To reinforce the plan, kgb officers established contact with other repatriates who were also leaving for Germany. They were informed that “Petrov” was an agent. It was hoped that they would report this to the German police, who would follow and check him.

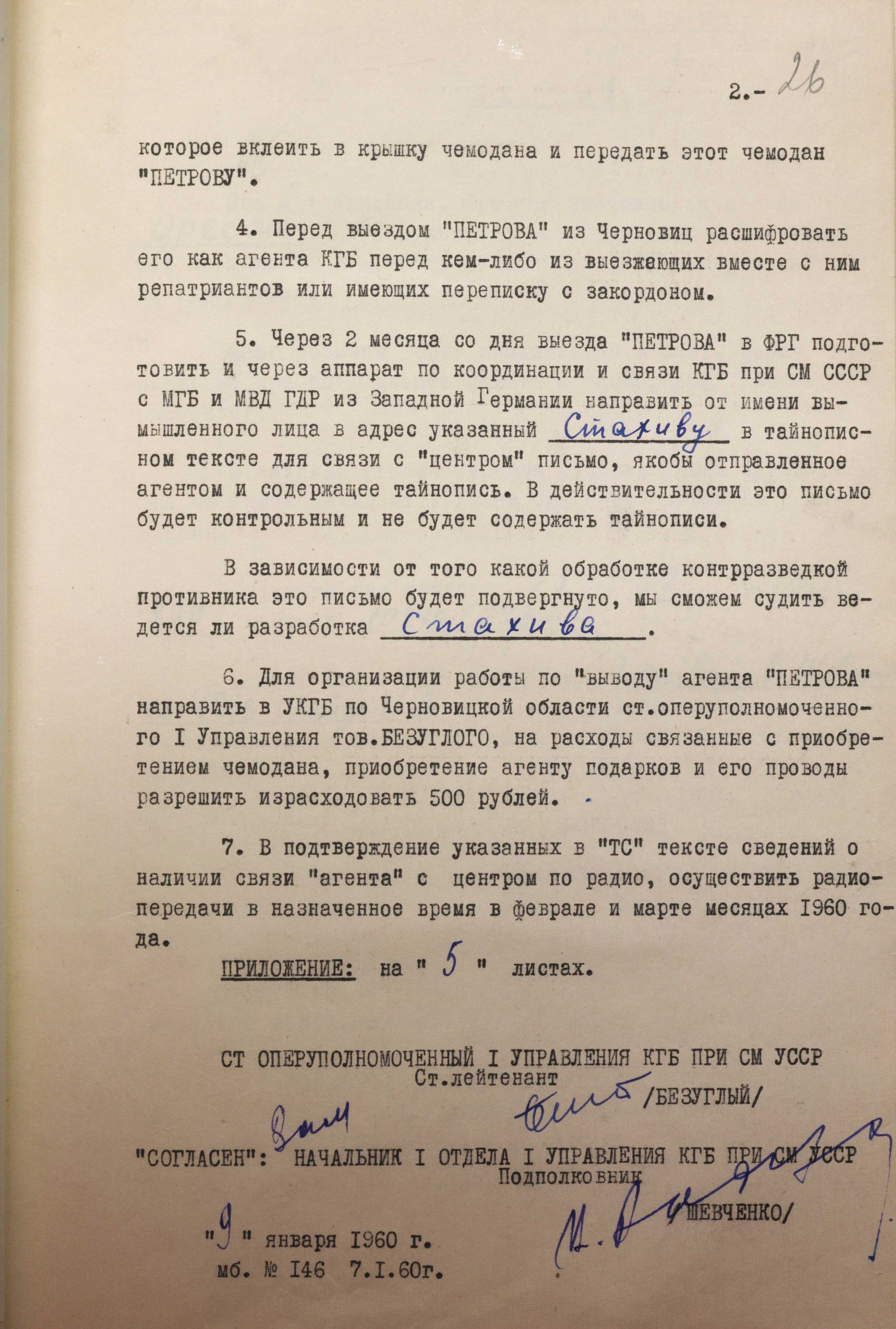

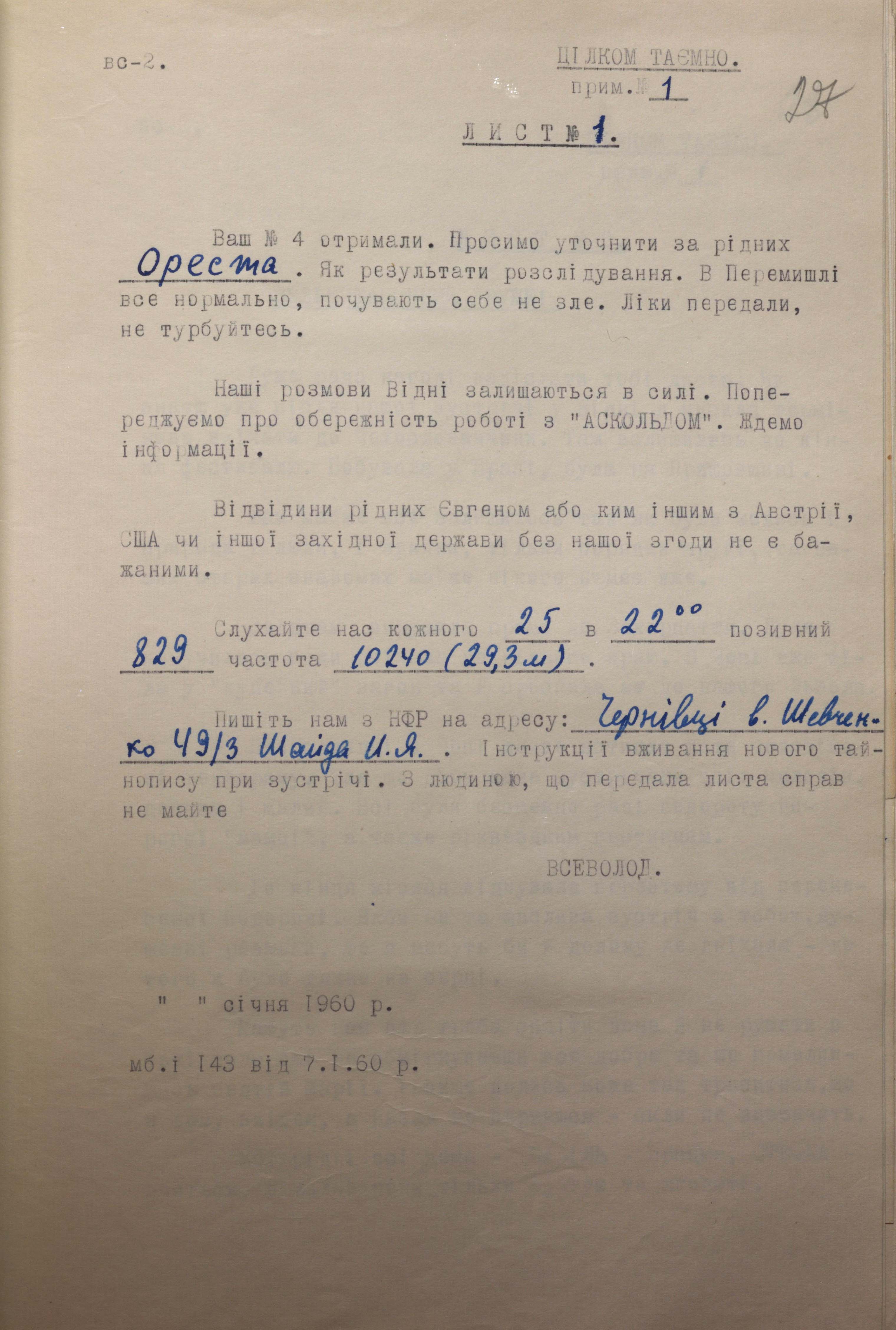

According to archival documents, several weeks passed after “Petrov”’s departure, but nothing happened – neither the detention of V. Stakhiv, nor news from “Petrov”, nor any loud debunking in the press. After some time, the staff of the Office of the ussr kgb Commissioner for the State Security of the German Democratic Republic took the following steps. In a changed handwriting, as if it were written by V. Stakhiv himself, they made an encrypted message which they sent by post from Munich to the ussr to the fake address mentioned in the first letter. They hoped that the German counterintelligence would intercept the letter, check it for cipher, read it, and eventually come at V. Stakhiv. To make it easy to read, the recipe for secret writing ink was the same as the one used before and already known to the German side thanks to the exposure of soviet agents in the past. Soon after, a letter was sent to Munich, allegedly for V. Stakhiv, also to a pre-determined fake address.

“...Everything is fine in Przemysl,” the encrypted text read, “They are well. Medicines have been sent, don't worry.

Our conversations in Vienna remain in force. We warn you to be careful when working with “Askold”. We are looking forward to information.

“Yevhen”’s visiting his relatives or anyone else in Austria, the United States or any other Western country without our consent is not advisable. Listen to us every 25th at 22.00, call sign 829, frequency 10240 (29.3 m).

...Instructions for using the new secret code when meeting. Do not have anything to do with the person who delivered the letter.

Vsevolod”

(FISU. – F.1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 2. – P. 27).

According to the case file, radio messages were repeatedly transmitted at the frequency specified in the letter. All in all, this lasted for months, but to no result. “Petrov”, being outside the ussr, obviously breathed a sigh of relief and did not bother to fulfill the kgb's tasks. He realized that this would only get him into trouble. There is also no information about whether the letters drew the attention of German counterintelligence.

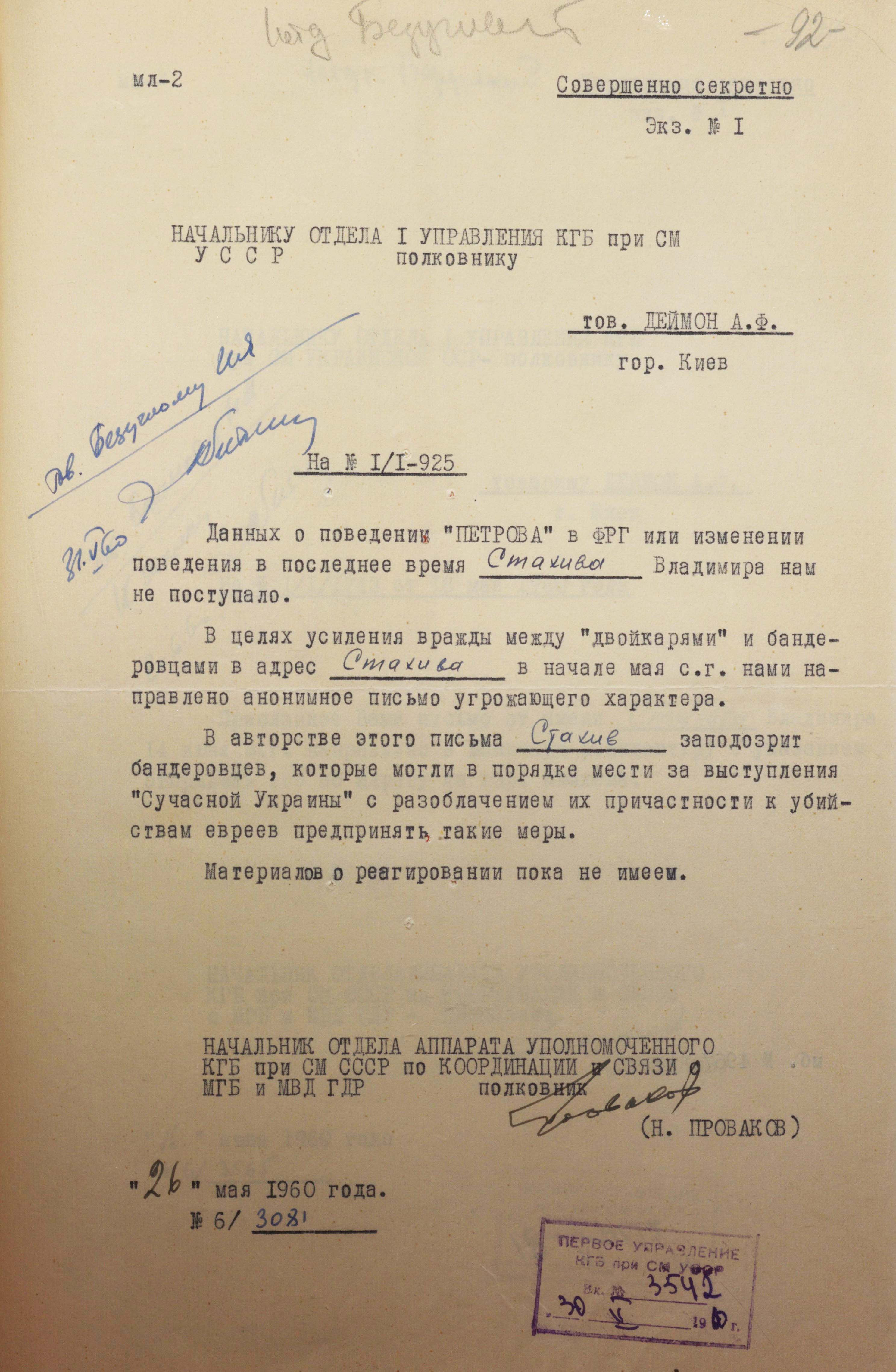

Six months after the start of the operation to compromise V. Stakhiv, the kgb of the Ukrainian ssr began to suspect that something had indeed gone wrong. So they resorted to other, more direct measures. “In order to intensify the enmity between the “Dviykari” (“Duo” – a new wing of the OUN Foreign Units led by “Duo”– Lev Rebet and Zenoviy Matla after the split – Transl.) and the Banderites,” the paper, dated May 1960, states, “we sent an anonymous letter to Stakhiv in early May this year with threats of reprisal. Stakhiv will suspect that the authors of this letter are Banderites, who could have taken such measures in revenge for the activities of “Suchasna Ukraina”...” (FISU. – F.1. – Case 11861. – Vol. 2. – P. 92).

But these threats did not affect V. Stakhiv's position. He continued to publish articles in newspapers characterized by the kgb as anti-soviet; continued to be a member of the UHVR's Foreign Office, a member of the Political Council of the OUNz (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists Abroad or “Dviykari”); and for some time was the head of the Union of Ukrainian Journalists in Exile in Germany. He wrote extensively about the history of the creation and activities of the OUN, about political assassinations by the kremlin leadership, in particular, in 1962, his brochure “The Trial of B. Stashynskyi” was published in New York by the “Prologue” Publishing House.

According to declassified documents, at different times, despite publicly demonstrating his political position and criticizing other currents in the OUN, programmatic provisions, and the views of some leaders, V. Stakhiv could be more restrained and tolerant in private communication with the same figures. For example, one of the kgb's papers mentions his meeting with Stepan Bandera in January 1959: “On January 8, at 5-6 p.m., the wedding of Bandera's activist Hryhoriy Komarynskyi took place in the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Munich. Stepan Bandera was wearing a new gray elegant coat and a black hat. All the time he was served by Bentsal. Kashuba and Zbrozhek were not present. Volodymyr Stakhiv came up to Bandera and wished him a happy holiday” (FISU. – F.1. – Sp. 11861. –Vol. 3. – P. 130).

This document shows that the collection of information about V. Stakhiv was carried out in different directions. The kgb was looking for the slightest opportunity to somehow influence him or get as close as possible. For this purpose, they also studied his close relatives. But this did not give them the expected results either. It turned out that the Stakhivs had always lived with the idea of restoring Ukrainian statehood, and all six children, following their parents, devoted themselves to the struggle for Ukraine’s freedom.

The parents lived in Przemysl. There was information about Yevhen – Volodymyr’s younger brother – that he also studied in Berlin, and on the eve of the German-soviet war he worked there with Volodymyr at the Ukrainian Press Service. There is no information in the case file about his membership at the beginning of the war in the Southern Marching Group of the OUN and his leading the Ukrainian nationalist underground in the Donbas in 1942-1943. As for his further activities, it is pointed out that until 1949 he was in Germany, then left for the United States, was a member of the leadership of the Foreign Office of the UHVR, and was an active member of “Dviykari” – the democratic wing of the OUN. In 1959, as a representative of the UHWR Foreign Office, he traveled to Vienna for the VII World Festival of Youth and Students, after which he visited his father in Przemysl.

The third brother, Ihor (known in the case as Myroslav), is reported to have allegedly emigrated to Argentina. Sister Maria was arrested by the Gestapo during the war and held in the Auschwitz concentration camp. After the war, she and her other sister, Iryna, lived in West Germany. Until 1947, the sisters were liaisons of the OUN Foreign Units, repeatedly crossing the border with messages to the OUN-Bandera regional Provid in Poland. It is mentioned that sister Olga allegedly went to Ukraine in 1944 with her husband on the orders of the OUN and died there under unclear circumstances.

Thus, the kgb failed to use close relatives to cultivate V. Stakhiv. And so did the article about him in the newspaper “Za Vozvrashchenie na rodinu” (“For the Return to the Motherland” – Transl.) in which he was portrayed as a servant of imperialism, an agent of American, British, and German intelligences, and a Ukrainian bourgeois nationalist. In the end, after all the attempts to compromise him, it was concluded that there were neither the necessary facts nor reliable agents in his environment. Besides, he himself did not care too much about any attacks from political opponents of the national liberation struggle. Therefore, the operational cultivation of V. Stakhiv was soon terminated and all materials went to the archive.

Meanwhile, Volodymyr Stakhiv continued his political and journalistic activities for almost ten years. Volodymyr Stakhiv passed away in 1971 in Munich.