Yurii Sheveliov. The nkvd/kgb’s “Linguistic” Studies

12/17/2024

The archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine have studied new materials on the prominent Ukrainian linguist, Slavicist, and literary critic Yurii Sheveliov (December 16, 1908 – April 12, 2002). They complement previously published research on the life and work of the scholar based on declassified documents, and shed light on the circumstances of the first manifestation of the nkvd’s operational interest in him, as well as the chekists’ targeted attention to his linguistic works throughout the decades that followed.

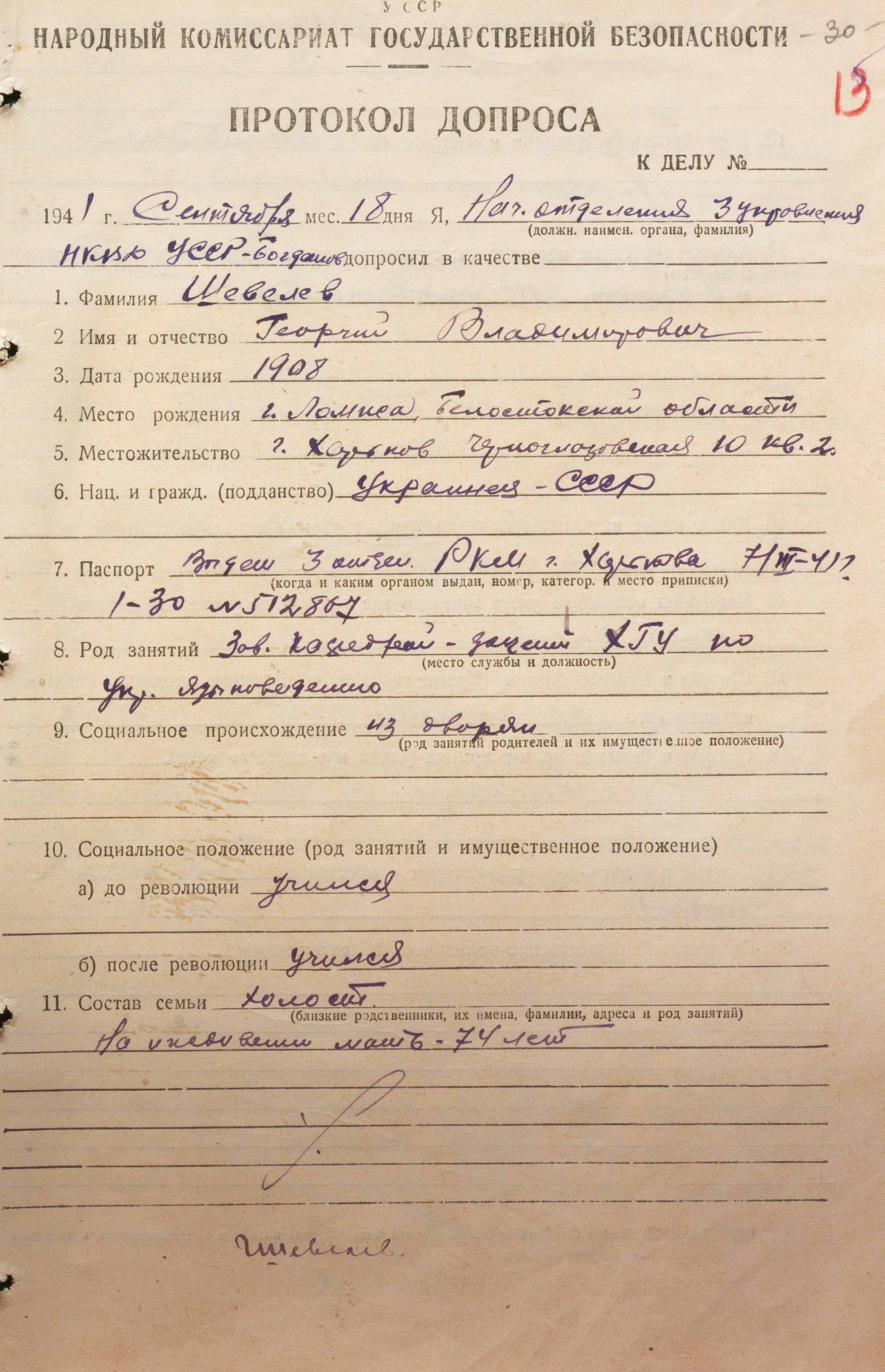

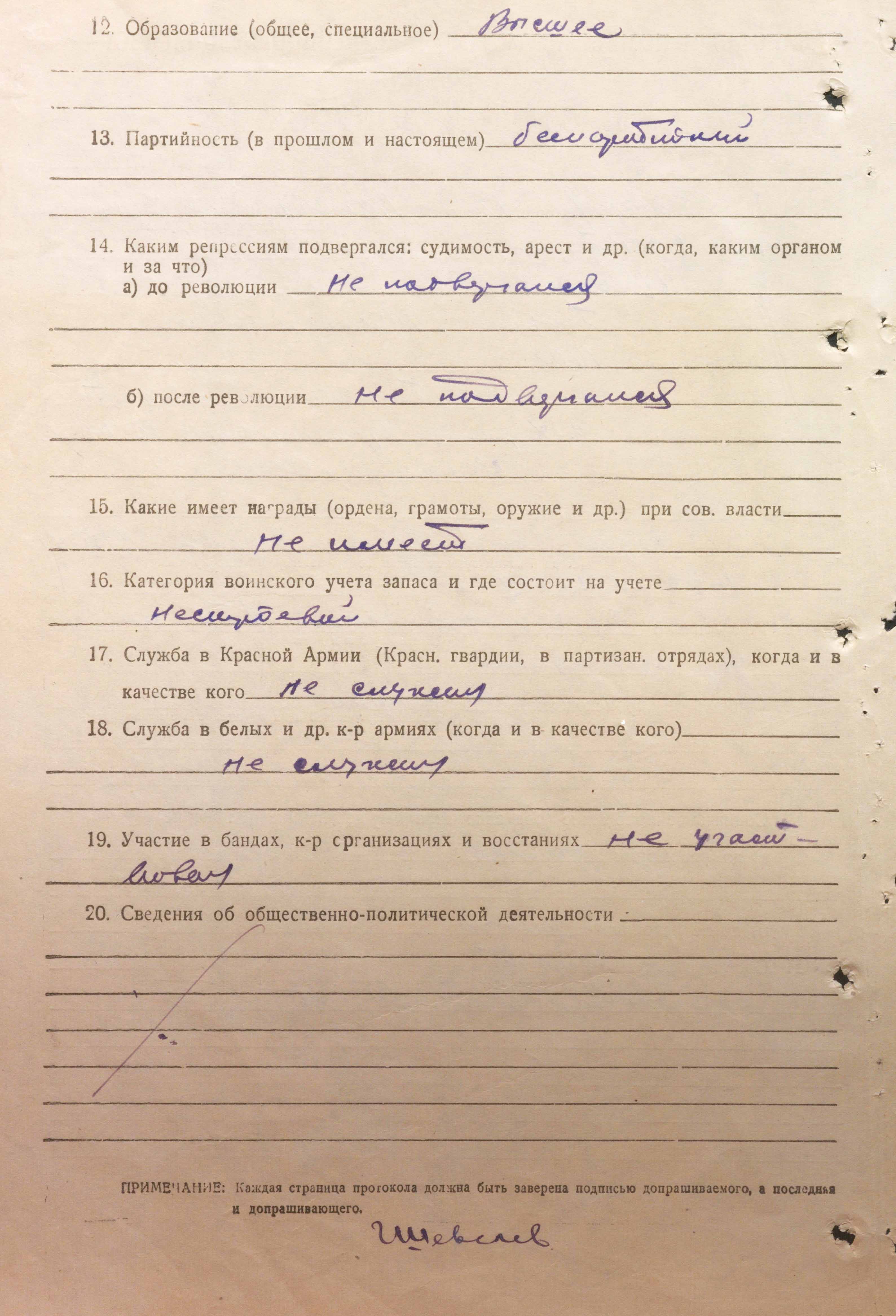

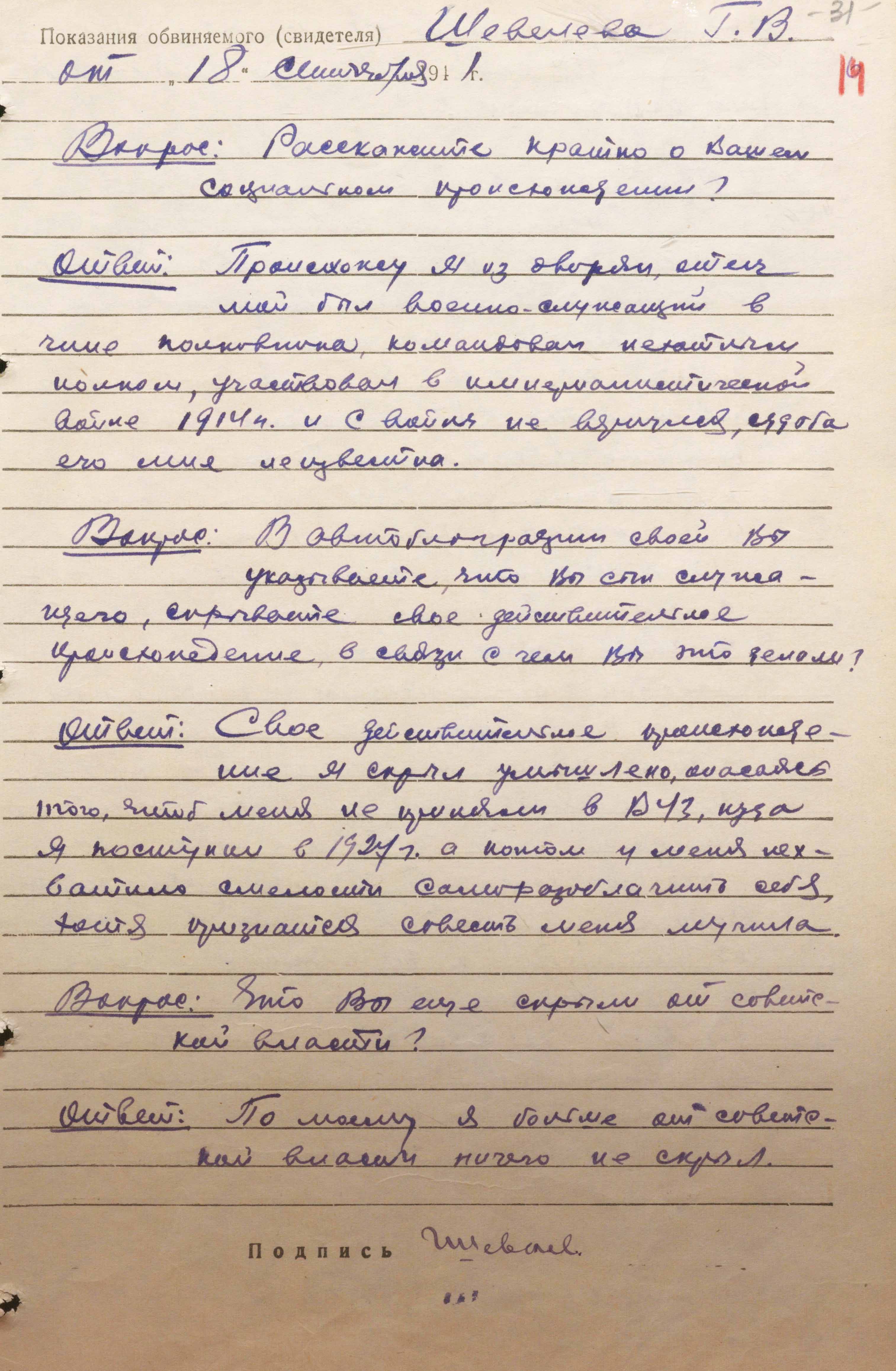

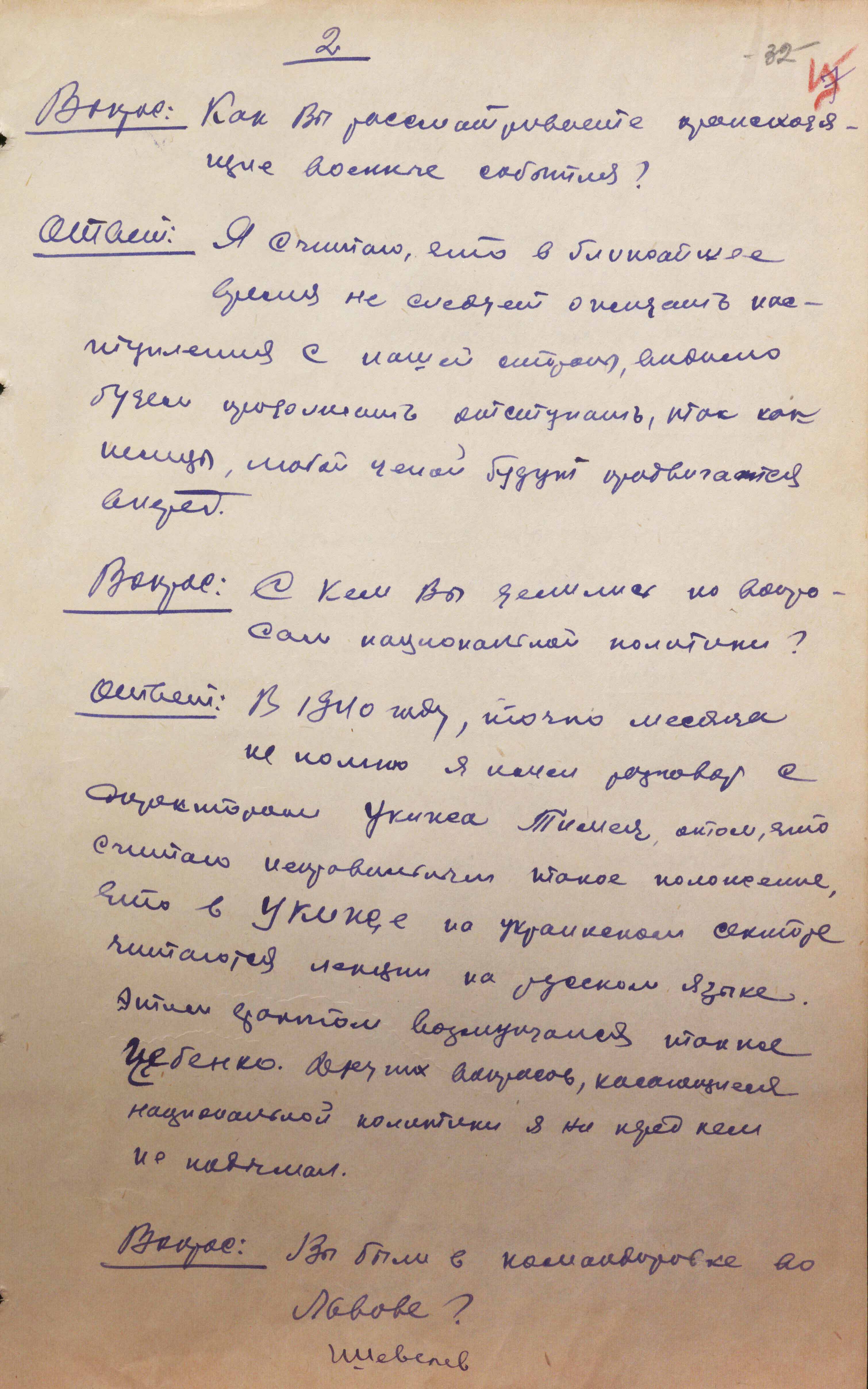

The analysis of the handwritten interrogation protocol of Yuriy Sheveliov dated September 18, 1941 from the archives of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine provides a lot of interesting information about the character of the scientist, his civic position, courage, and sense of self-esteem. It was the fourth month of the German-soviet war. Hitler's troops were steadily moving closer to Kharkiv, where Yu. Sheveliov lived and worked at a local university as the head of the Department of the Ukrainian Linguistics. At the same time, despite the tense military-political situation and preparations for evacuation, the nkvd of the Ukrainian ssr did not stop the operational cultivation of persons on political grounds.

According to archival documents, almost until the occupation of the city, the “Blok” agent cultivation regarding the “reactionary professorship of Kharkiv University” had never stopped. In the report to the management, Senior Lieutenant of state security Bohdanov was pointing out that Yu. Sheveliov was on good terms with the university's leading teachers, Leonid Bulakhovskyi, Oleksandr Biletskyi, Volodymyr Tsybenko, and others who were involved in the case. Therefore, he asked for permission to summon Sheveliov for interrogation in order to see if he possibly could be used in further cultivation of those persons.

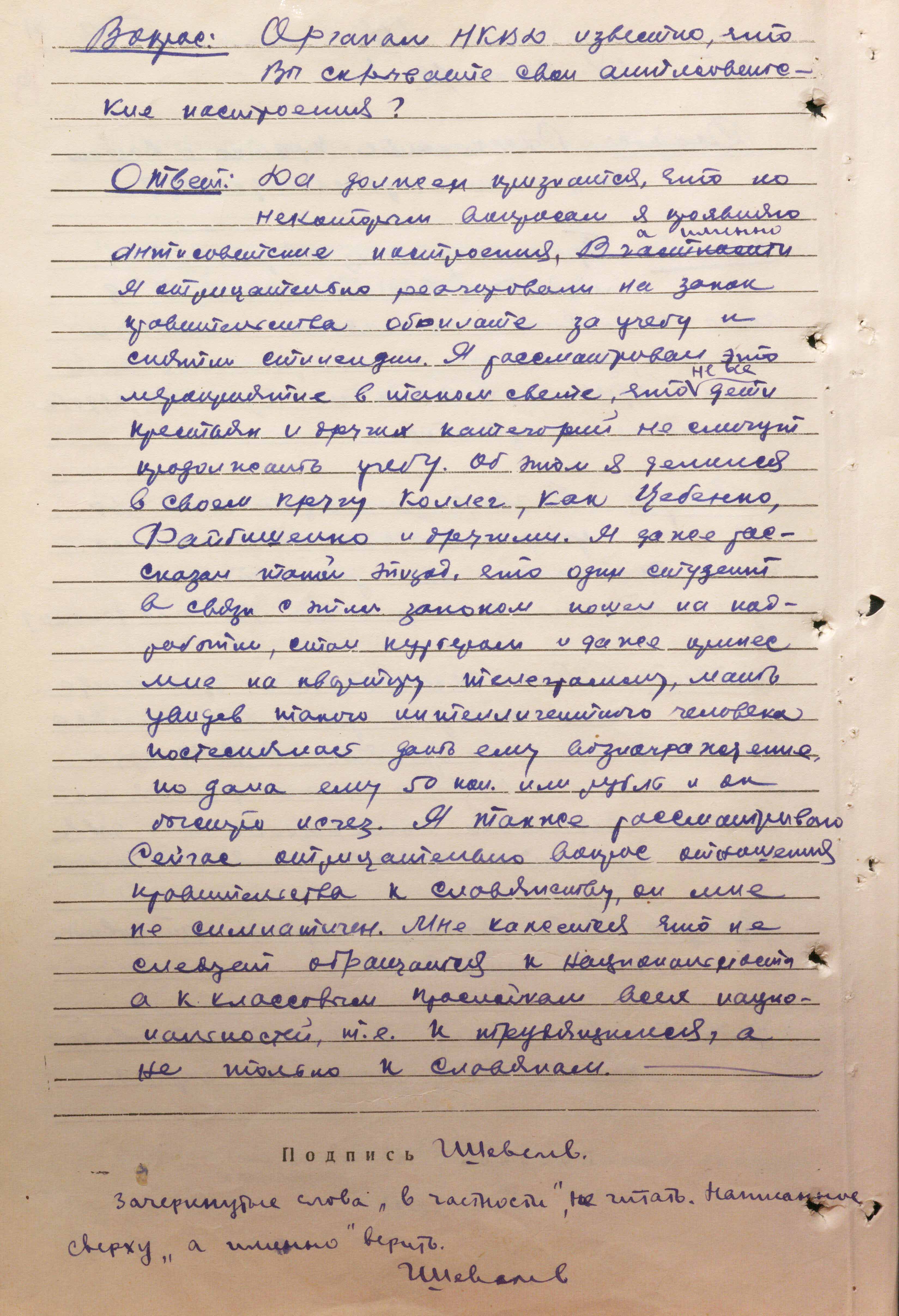

The interrogation took place on the same day. Among other things, the nkvd officer was interested in Yu. Sheveliov’s views regarding national policy. The latter would frankly say that it was unpleasant for him to see how the government was treating the national issue. In response to clarifying questions, he pointed out that he had a conversation about this with the Director of the Ukrainian Institute of Journalism and complained to him that lectures were in russian in the Ukrainian sector of the Institute.

Operational and intelligence reports state that he also discussed those issues with professors and academicians during his trip to Lviv. In addition, he spoke about the defeat of the ussr in the war with Finland, calling it “a worthless embarrassment for a great power” and criticized some other aspects of soviet policy. It is also mentioned that back in 1928 he published articles in defense of the Ukrainian theatre director and filmmaker Les Kurbas, who at that time “was under the heavy fire from all proletarian criticism”.

Apparently, the nkvd simply did not have enough time to fully cultivate Sheveliov himself and bring him to justice or make him cooperate. The war got in the way. Attempts to make up for time lost in the 1950s – 1970s were in vain. By then, he had already gained a name and authority in the scientific world. That’s why, first, they decided to ignore and silence his research and achievements in the ussr, then they resorted to creating obstacles to his participation in international congresses of Slavic studies under false pretenses. And after all of this failed, they decided to encourage him to return to his homeland by promising him all kinds of assistance in his scientific work. Archival documents reveal some new aspects of how all this was happening.

A kgb document based on the materials of the emigration journal “Suchasnist” (Issue 2, 1969) states that in the postwar period some of Shevelyov's studies were published in the Ukrainian ssr, but without attribution. In particular, the “Course of the Modern Ukrainian Literary Language” published by the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian ssr contained a chapter written by him in 1940, but the publishers “forgot” to mention his name. “This first adventure of mine in the soviet union was pleasant”, Sheveliov pointed out with humor. “It was nice to speak with a full voice... to thousands of Ukrainian students. As for the surname... Forget about it. Besides, I was not me then, but Yuriy Sherekh. Anyway, I did not receive royalties” (BSA of FISU - F. 1. – Case 11890. - P. 227).

As mentioned in the reference, Sheveliov complained that references to his works published abroad had disappeared, and he was surprised to learn from bibliographic data that he had allegedly never published anything in Ukraine before the war. In 1963, his review of Ukrainian and Belarusian linguistics was published. “The reviews in the West are approving”, a paper quotes him saying, “in the East... they ignore”. Then, along with the policy of silence, criticism began. In the journal “Voprosy Yazykoznania”(“Issues of Linguistics”- Transl.) the “bourgeois scientist” was criticized for his statement that “the stalinist period in soviet linguistics was not much different from the marxist one”. He was criticized for his statements about stagnation in soviet linguistics and its politicization. But there was more to come.

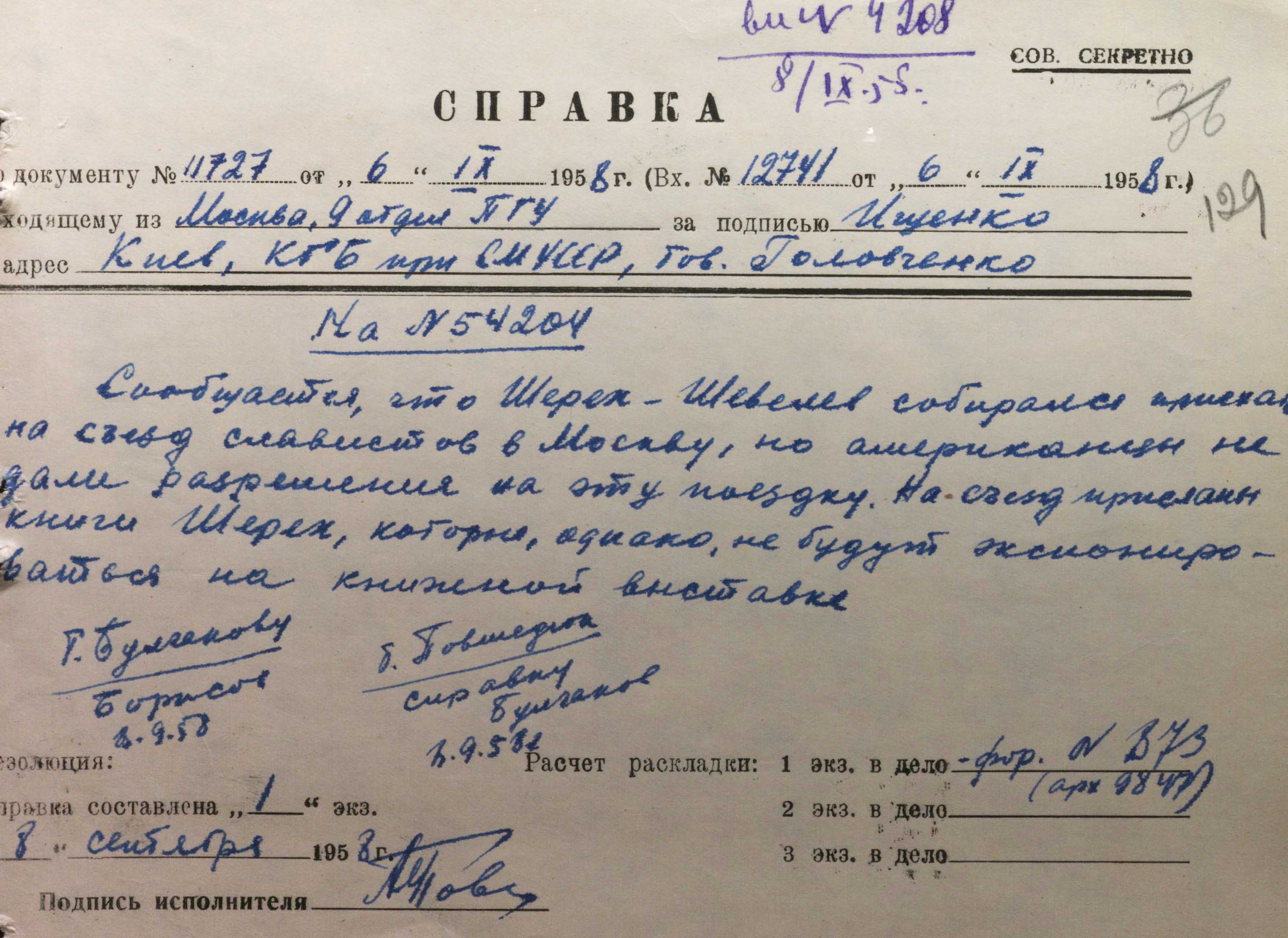

“In the mid-fifties”, Sheveliov is quoted, “it was decided to restore the tradition of international congresses of Slavists, and the first one was convened in 1958 in moscow. I did not participate in the congress. But there was an exhibition of publications. I was asked to submit my publications and I did so. They were on display for a short time. Long before the end of the congress, they disappeared from the stand. The American delegation filed a complaint. They were told that the publications had been removed at the request of the Ukrainians” (BSA of FISU - F. 1. - Case. 11890. - P. 228).

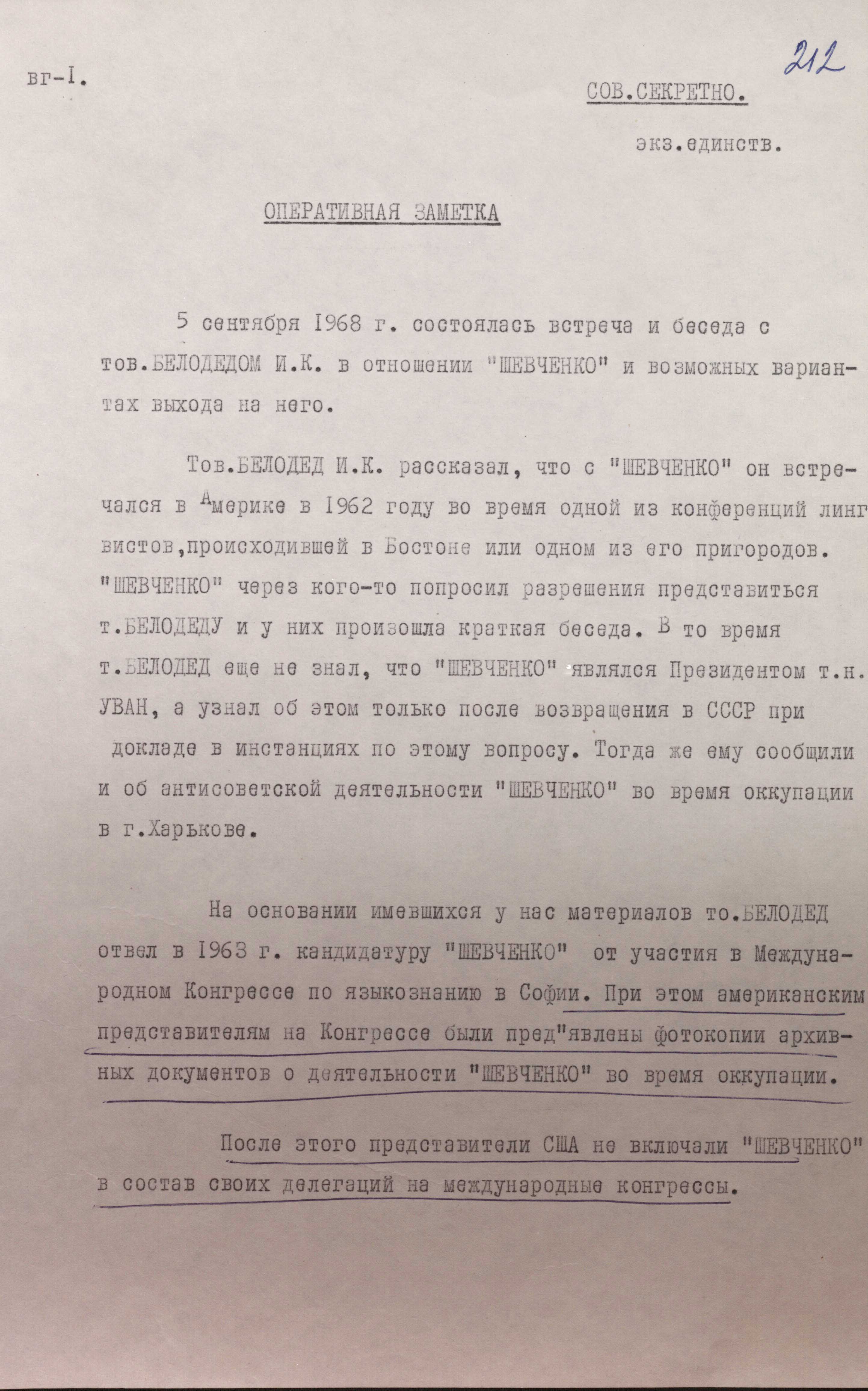

The archival documents make clearer the circumstances of interfering with Sheveliov's participation in International Congresses of Slavists. At that time, representatives of the ussr and the countries of the communist camp took a leading place in the organizing committees of such events. Therefore, they could influence the decision-making process – who should be included in the lists of honored scholars and who should not. In particular, this happened in 1963, when the commission for convening such a congress, initiated by Academician Ivan Bilodid, then the Director of the Institute of Linguistics at the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian ssr, decided that it was inappropriate to invite Yuriy Sheveliov.

This is how it is explained in one of the kgb's papers:

“On the basis of the materials available to us, comrade Bilodid withdrew “Shevchenko”'s candidacy in 1963 from participation in the International Congress on Linguists in Sofia. At the same time, photocopies of archival documents about “Shevchenko”'s activities during the occupation were presented to the American representatives at the congress. After that, the US representatives did not include “Shevchenko” in their delegations to international congresses” (BSA of FISU - F.1. – Case 11890. - P. 212).

In fact, Yu. Sheveliov, who goes by the pseudonym “Shevchenko” in the documents, did not cooperate with the Nazis during the occupation of Kharkiv by Hitler’s troops, but was engaged only in scientific and literary work, compiling and publishing textbooks on Ukrainian spelling, and writing for the local press. This is also stated in eyewitness accounts collected by the mgb/kgb. At the same time, a different piece of information was fabricated for the international organizing committee, which no one bothered to check. The so-called solidarity of participants from the countries of the anti-Hitler coalition did work.

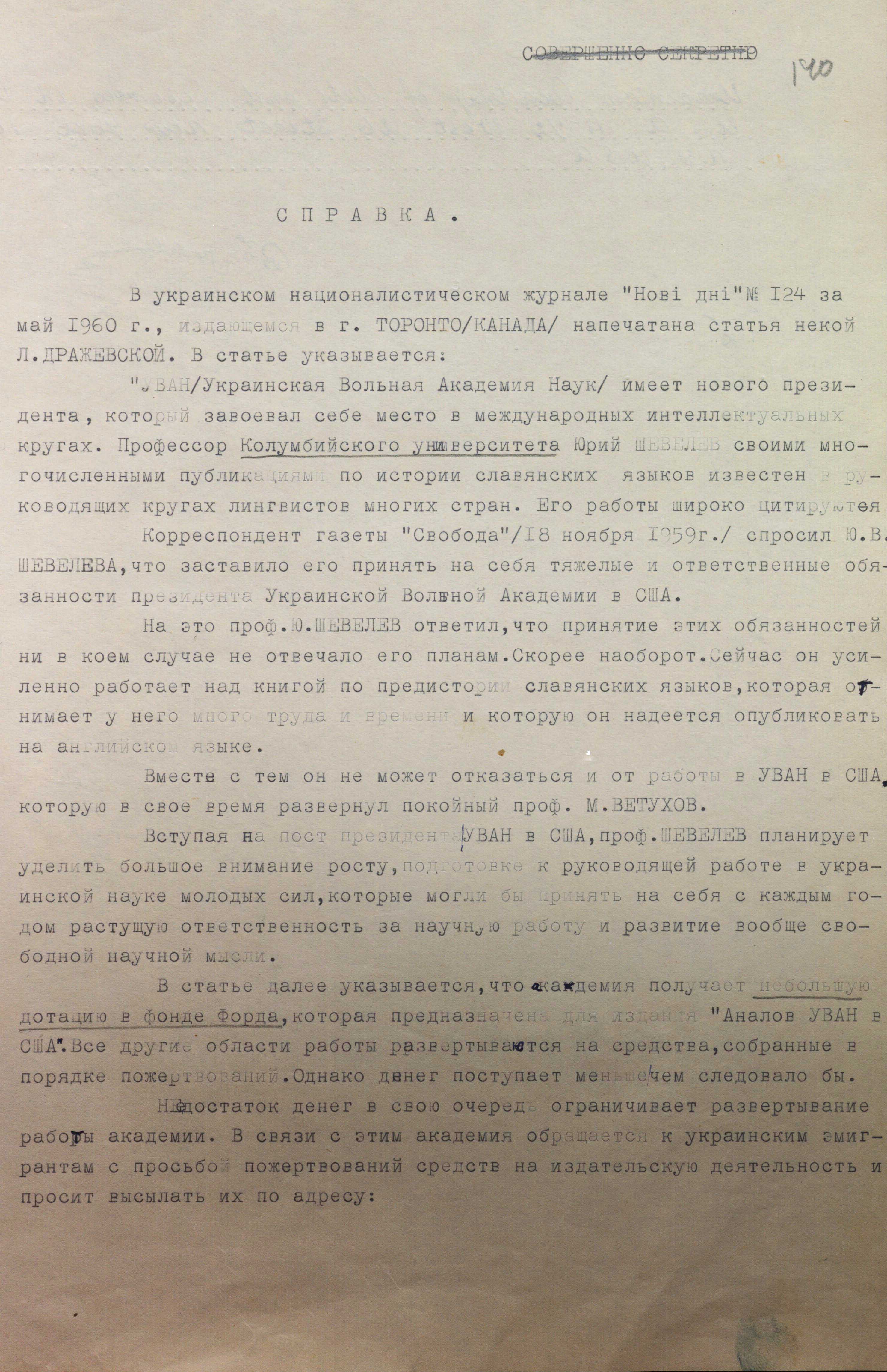

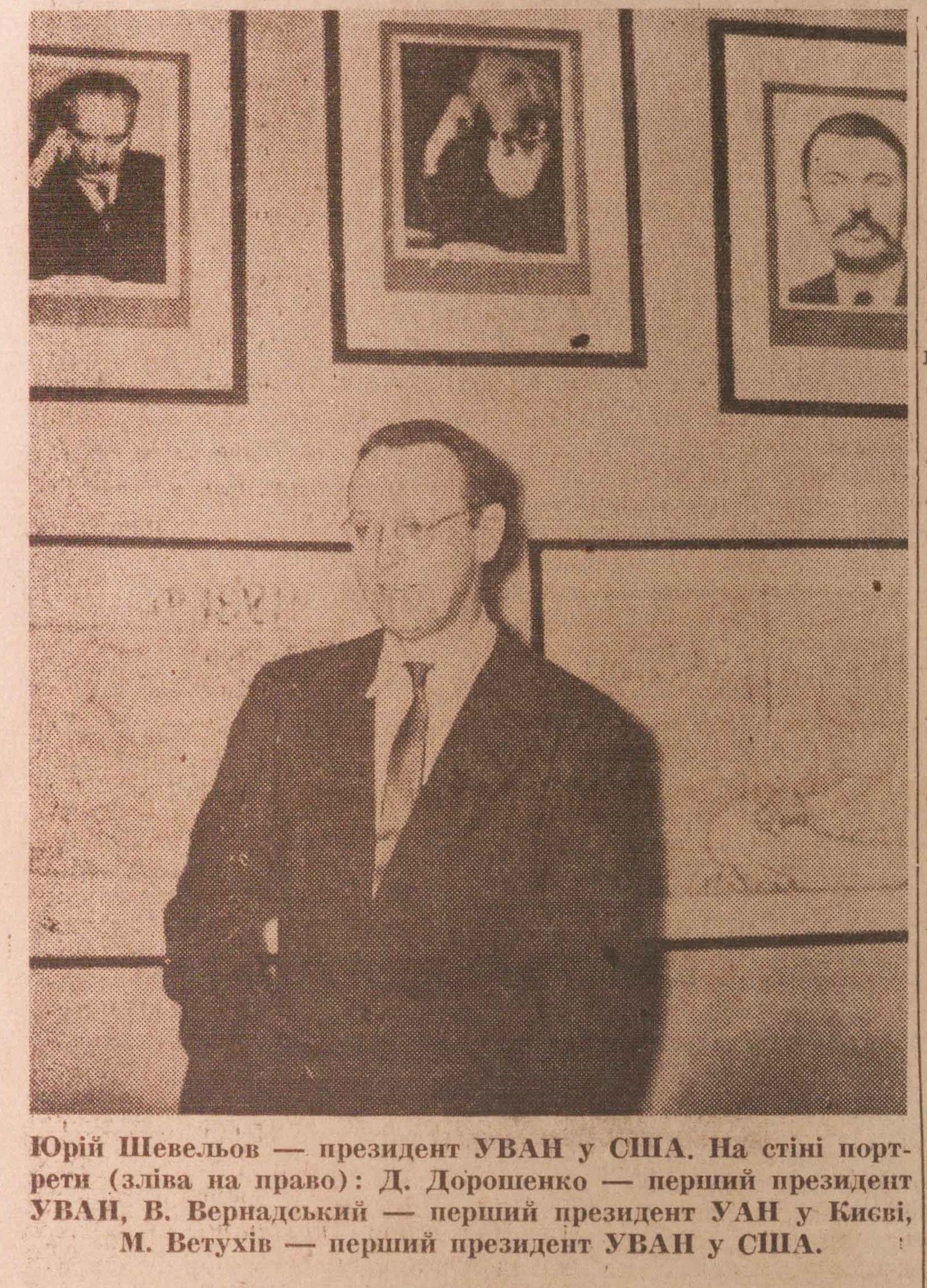

Despite this, Yu. Sheveliov did not make any political statements, did not openly criticize the policy of the ussr, but persistently continued his scientific and public activities and had considerable achievements in this field. One of the kgb's papers, dated 1960, provides the following information about him with reference to a publication in the Ukrainian emigrant magazine “Novi Dnі”(“New Days”- Transl.):

“UVAN (Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences) has a new President who has won a place in international intellectual circles. Professor of the Columbia University Yuriy Sheveliov is known in the leading circles of linguists in many countries for his numerous publications on the history of Slavic languages. His works are widely cited...

Taking office as President of the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences in the United States, Professor Sheveliov is going to pay special attention to the growth and preparation for leadership in Ukrainian science of young forces who could take responsibility for scientific work and development of free scientific thought in general”

(BSA of FISU. - F. 1. – Case 11890. - P. 140).

Another issue of the magazine contains congratulations to Y. Sheveliov on the occasion of his election as President of the UVAN, which is quoted verbatim in another kgb document. “...Yuriy Sheveliov is not only a highly respected person among Ukrainian and American scholars”, the text says, “but also a person respected by the majority of Ukrainians in exile. Beside, although Yuriy Sheveliov is known mostly as an excellent critic and publicist, he is also an outstanding scholar of philology. In American academic circles, he is spoken of as a prominent philologist of our time. Currently, Yuriy Sheveliov is working on a major scientific work on the origins of the Ukrainian language. The work is to be published in English. In order for him to work, Columbia University released him from lecturing for a year...” (BSA of FISU. - F. 1. - Sp. 11890. - L. 148).

Such praises for Yu. Sheveliov and his authority among scholars in the world obviously played a role in changing the kgb's attitude to his operational cultivation. According to archival documents, writers, journalists, and scientists were repeatedly sent to meet with him in the United States to persuade him to return to the ussr and continue his scientific and journalistic studies in the conditions of soviet reality.

But to the last moment, he did not give his consent even for a one-time trip, fearing some kind of provocation or even possible detention. The lesson from his contacts with nkvd officers in 1941, interrogations, and the words from his non-disclosure agreement (not to share the information that he learned during the conversation and the fact of interrogation itself) was not lost on him. He spoke frankly about all of this abroad to his friends and publicly in his memoirs. He even consulted lawyers about the consequences of his frankness. At the same time, as a professional who had studied the works of many Ukrainian writers, he did know the difference between freedom of speech and creativity in democratic and in totalitarian societies.